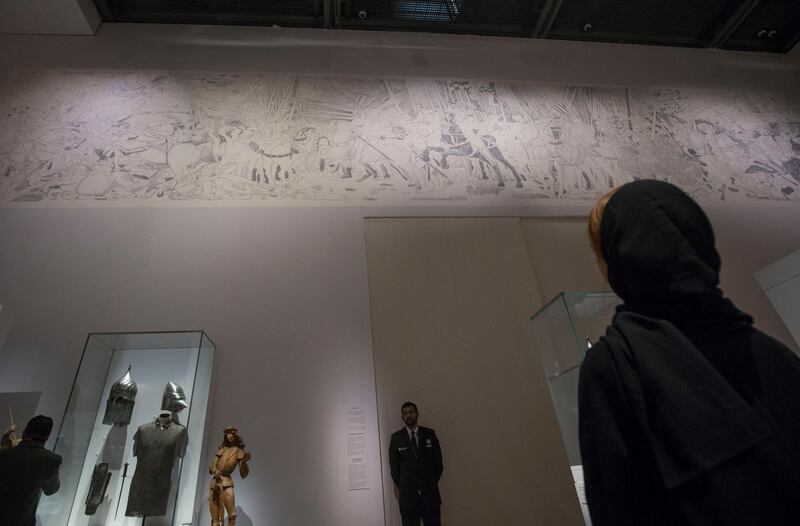

Majestic knights on horseback tower over visitors as they enter Louvre Abu Dhabi’s latest exhibition, Furusiyya: The Art of Chivalry between East and West. Both figures are in full armour – one, which dates back to the 15th-century Ottoman Empire, is covered in dark chain mail, his horse donning steel plates; the other from 16th-century Europe wears a military skirt and a feather panache. It is a fitting introduction to the show, which presents a comparative study between the knightly cultures of the Islamic and Christian worlds of East and West.

On view are more than 130 artefacts, from weaponry and armour to manuscripts and decorative objects. This includes swords, crossbows, turban helmets and medallions, as well as items of artistry such as ceramic bowls, reliefs and tapestries. Divided into three sections, the exhibition examines the emergence of horse riding, warfare and the lives of knights in both cultures.

The tradition of furusiyya, which thrived in the Mamluk Dynasty around the 10th to 16th centuries, involved hippology, or the study of horses, equestrianism, swordsmanship and archery. In medieval Europe, knighthood meant mounted warriors who encompassed ideas of chivalry and a code of conduct closely tied to Christian influences.

East meets West at Louvre Abu Dhabi's latest exhibition

Beyond these definitions, the exhibition's real pull are the insights into medieval warfare, not only in terms of weapons, but the values that encouraged these knights as they went into battle. In the East, furusiyya practices were borne out of military clashes between dynasties and empires as they struggled for control. In western Europe, the Hundred Years War between England and France fuelled the need to perfect combat skills.

While the exhibition fascinates with the rarity and monumentality of some of its displays, it does sacrifice finer points of historical detail for simplicity. For one, the term "East" covers a much broader geography and period, including Persia and the Near East, with places such as Turkey and Egypt. Historically speaking, the traditions of furusiyya and chivalry, though both rooted in elements of horsemanship and warfare, developed separately from each other. Still, their practices were drawn from the same roots: the Central Asian steppes, Persia and the Celts in Gaul.

Curated by Elisabeth Taburet-Delahaye, Carine Juvin, and Michel Huynh, the exhibition attempts to continue the narrative that Louvre Abu Dhabi has been fostering since its inception – finding connection and commonality that transcends geography.

This encounter between eastern and western cavalries has been carved into one piece – a particularly exquisite sardonyx from third-century Iran that depicts the capture of a Roman emperor by a Persian Shah. The rest of the exhibition's first chapter titled "Riding" centres on the figure of the mounted warrior, exalted in both cultures. In fact, these figures were godly, as revealed in a marble relief from Syria that depicts Genneas, a rider-god known to protect Arab merchants in Palmyra province. Horsemen figures appear in ceramic ware, too, such as a bowl from 12th to 13th-century Iran that renders the Central Asian riders that passed through the region in the 11th century. In the West, the figure of the knight was held in high esteem, as seen in the funerary effigy of Geoffrey Plantagenet placed on an enamel plaque. It shows the Duke of Normandy in fine attire, holding a posture that speaks to his authority.

It's hard to argue with history, however, and the differences between the two traditions arise time and again, which the curators are quick to point out. For one, chivalry in the West propped up the aristocratic traditions of the time. Knighthood was hereditary, and required training from childhood and sizeable sums for weapons. In the East, youths could enroll to become fighters and learn furusiyya practices in preparation for battle.

These differences become more stark in the "Fighting" section, in which the displays will spark the imagination of many visitors, conjuring up images of warriors in armour, riding across battlefields. There are a variety of swords from East and West, with the former preferring single-edged and curved, with the latter using double-edged and straight ones.

In furusiyya tradition, the crossbow was a fearsome and commonly used tool. The complexity behind their construction can been seen in the ballista bolt from 13th-century Iran and a reconstructed crossbow from 11th-century Syria, both shown side by side in the exhibition. Along with bows and arrows, these were effective weapons that were hardly used by medieval knights, who preferred to be in direct combat with their enemies.

The final section pulls these two traditions even further apart, showing how combat influenced the development of knightly pastimes, and the literature and art that sprung out of these cultural practices. While both furusiyya and chivalry upheld values courage and honour, these were demonstrated by knights in incredibly divergent ways.

The practice of jousting, for example, was common in medieval Europe. Knights would battle it out in tournaments using lances, sometimes the matches would be fought to the death. These tournaments were not only a form of entertainment, but also a show of the combatant's fighting spirit and their bravery in the face of danger. These piercing lance tips, on display at Louvre Abu Dhabi, give an idea of how brutal these jousts could get. Carved ivory mirror boxes also show the significance of these practices in aristocratic society, and how they came to be embedded in material culture.

In contrast, the furusiyya riders entertained themselves in other ways, with sequences of troop movements with their horses and games of polo. They also played chess, and two exquisitely carved chess pieces – one depicting a knight's battle with a dragon – are on display in the show, on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

While chivalry is known for its concept of courtly love and romance, which focused on the personal relationship between a knight and noblewoman, the furusiyya literary tradition focused on the heroic adventures of characters such as the Sultan Baybars. Through these literary texts, the knightly concepts of loyalty and bravery spread across society and became ingrained in its social values.

Furusiyya: The Art of Chivalry Between East and West runs from Wednesday, February 19 to Saturday, May 30