Scientists claim to have identified a new, more contagious form of the Covid virus, and warn it may lead to people who recover becoming re-infected.

The mutant form of the virus was first observed in Europe in February, then spread to the United States. It is now the most common form of the virus worldwide.

While the research, made by an international team, is yet to be peer-reviewed, the emergence of a new strain of the virus has raised concerns about the effectiveness of vaccines now under development.

However, many experts have questioned the research and its significance. They include Dr Francis Collins, director of the US National Institutes of Health, who told The Washington Post that the paper "draws rather sweeping conclusions".

The researchers, led by biologist Dr Bette Korber of the US Los Alamos National Laboratory, base their conclusions on genetic studies of thousands of examples of the SARS-CoV-2 virus reported to an international database.

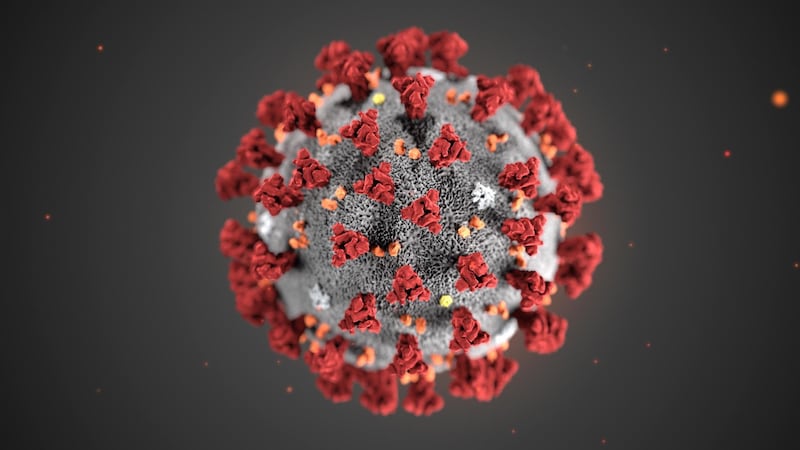

They identified one strain with a mutation in the genetic instructions for the so-called spike proteins that stick out from its surface. These are used by the virus to infect healthy cells, triggering Covid-19 which has so far killed over 250,000 world-wide.

Analysis by the team suggests that the mutation, known as D614G, rapidly spread throughout Europe, becoming the dominant form of the virus just a few weeks after its appearance.

They claim that the mutation may boost the virus’s ability to break into healthy cells. “D614G is increasing in frequency at an alarming rate, indicating a fitness advantage relative to the original Wuhan strain that enables more rapid spread”.

To investigate whether the mutant form is also more harmful, the team studied its prevalence among over 450 Covid patients in hospitals in Sheffield, England.

The patients typically had greater levels of the virus. However, tests found no compelling evidence that the new strain increases the risk of serious illness.

According to the team, the rapid spread of the new strain raises the possibility that the mutation makes it more able to evade the body’s immune system. This, the team cautions, may leave patients “susceptible to a second infection”.

There may also be consequences for the design of vaccines, widely regarded as the best hope of ending the pandemic.

Coronavirus death toll surpasses 250,000

The team report that while they had planned to identify mutations that might undermine future vaccines “we did not anticipate such dramatic results so early in the pandemic”.

Responses to the research have been mixed.

Dr Jonathan Stoye, head of virology at the Francis Crick Institute, London, said that while the importance of the mutation has yet to be established, the study “shows that SARS-CoV-2 can alter its genetic structure in multiple ways as it spreads around the world”.

Dr Stoye added that this is “likely to have important implications for vaccine development.”

However, others expressed scepticism about the claims, pointing out there is little evolutionary pressure on the Covid virus to become more contagious as there are still huge numbers of people open to infection.

Instead, the mutant strain may simply have benefited from emerging in Europe, a region with a relatively old and vulnerable population. This allowed the new strain to trigger a surge in cases, creating the false impression it is more infectious.

Researchers also questioned the implications for vaccine development.

According to infectious disease expert Professor William Hanage of Harvard University, it is unlikely that a single mutation in the virus will prevent vaccines from working: “The virus would have been awfully lucky to have landed on the escape mutation from all these vaccines so early”.

Prof Hanage added: “Any vaccine will be tested to see if it provides protection against circulating strains”.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Professor of Science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK