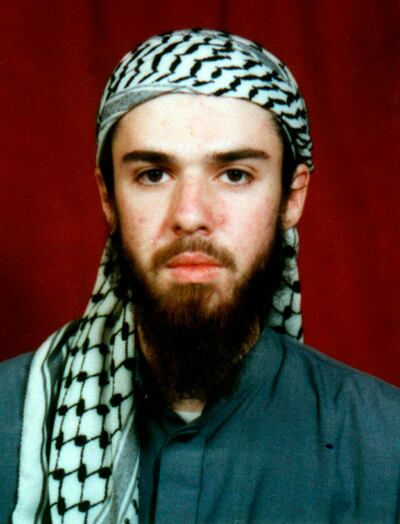

Few people have defined America's post-9/11 homegrown terrorist threat like John Walker Lindh, the so-called "American Taliban". On May 23, having served 17 years of a 20-year sentence for aiding a terrorist organisation, Walker Lindh walked free from a high-security prison in western Indiana having been released early for good behaviour. Yet despite the long years he spent behind bars, it appears his extreme views may not have wavered at all.

In letters exchanged with a television producer while in prison in 2015, Walker Lindh told of how he spent his days in pursuit of pure Islamic knowledge, and that he considered himself a political prisoner. Four years ago, as ISIS slaughtered and raped across Syria and northern Iraq, Walker Lindh referred to the terror group as “doing a spectacular job”, according to KNBC, an affiliate of NBC News.

A 2016 intelligence document from the National Counter Terrorism Centre, a US government agency, reported that Walker Lindh, despite having spent 14 years in a "correctional facility", continued to be an advocate for global jihad. A year later, Foreign Policy magazine claimed that he was involved in writing and translating extremist texts while behind bars.

But now, having served his time, Walker Lindh is free to enjoy life like any other American.

Now and over the coming five years, prison time for a deluge of extremists is coming to an end. Najibullah Zazi, an Al Qaeda recruit who plotted to bomb the New York subway, was released in May after serving a 10-year sentence. As many as 80 individuals jailed on charges of providing material support for foreign terrorist organisations are eligible for release before 2024, including dozens incarcerated on ISIS-related offences.

It raises a critical question: What is the plan to reintegrate them back into society?

Walker Lindh’s case has brought into sharp focus the dearth of post-prison support for people who have served time for extremist activity. Incredibly, no specific national programme exists to help reintegrate convicted extremists into everyday life. Unlike other countries, "the United States has neither established a formal rehabilitation and re-entry programme for convicted terrorists nor developed infrastructures to support individuals upon their release", reports a recent study by the Counter Extremism Project, an international policy organisation.

Experts fear that unreformed extremists pose a terrorist threat to the country. “They are undoubtedly a time bomb waiting to go off,” says Mubin Shaikh, a Canadian counter-extremist expert and one-time Taliban affiliate, of those soon to be released. “There’s nothing to indicate their animus has changed. If anything, now they’ve only become worse because they’ve been put in a bad place. US prisons are not exactly known for their rehabilitative effect. What tells you they’re going to come out any better?”

Some groups in the US are attempting to take matters into their own hands. A Tennessee-based organisation called Parents For Peace, established by family members of young men radicalised and recruited by extremists, has a hotline that people can call if they fear a loved one is being radicalised.

In Minnesota, where dozens of young men from the 100,000-strong Somali-American community in Minneapolis were targeted by ISIS and Al Shabab online recruiters and travelled to Somalia and Syria in recent years, America's first deradicalisation programme was launched two years ago. Named the Terrorism Disengagement and Deradicalisation Programme and founded by a former senior probation officer, its core efforts focused on establishing a wide network of community support for radicalised youths with significant input and monitoring on the part of their families, friends and religious leaders.

The Minnesota experiment found that 10 of the 12 individuals selected for the programme successfully completed their court-ordered term of supervision. About a dozen others were considered unsuitable to take part, based on factors including their flight risk and a lack of willingness to admit guilt or express remorse.

Similar models have been tried in countries such as Belgium. In 2014, the town of Vilvoorde north of Brussels saw dozens of its young men leave to join ISIS in Syria or Iraq. The mayor launched a hands-on deradicalisation plan that sought to reclaim Islamic vocabulary co-opted by ISIS online recruiters, and establish a network of close friends and family around at-risk youth. Since then, the town has reported not a single attempted departure.

And while Islamic extremism attracts significant attention from a host of influential US government intelligence and security agencies, some believe their role in reintegrating ex-convicts into the world should be limited. Deradicalisation “should not be a government thing; top-down government-driven efforts are going to fail because they do not come from the at-risk communities,” says Mr Shaikh. “In order for there to be any significant social change within the communities, it must be led by the community. That’s just a given.”

As successful as the Minnesota project may have been, it sorely lacked funds and scale, according to its architect, Kevin Lowry, who previously served as Minnesota's chief probation officer. “When I visited the Prevent programme in the UK in 2015 [a government counter-terrorism initiative] they had an annual budget of $67 million [Dh246m] … the United States has not seen that kind of effort or commitment to finances.”

Several people convicted for extremist offences in Minnesota, Ohio and other states have been ordered by judges to stay in halfway houses – designed to help people convicted of alcohol and drugs crimes transition back to civilian life – as there are no other appropriate facilities available. Now that ISIS and Al Qaeda are all but defeated on the battlefield in Syria means that counter-extremism agencies could, should they choose, turn their attention to supporting deradicalisation efforts, financially or in other ways.

Unlike many others who have been jailed for similar crimes, Walker Lindh, now 38, is subject to a series of restrictions after his release. He is believed to have settled in northern Virginia, and his access to the internet is monitored. He must attend mental health sessions and is banned from foreign travel, despite having acquired an Irish passport (through his paternal grandmother’s Irish roots) while in prison. Some believe the restrictions placed on Walker Lindh speak to the high level of concern authorities continue to have about him.

For Mr Shaikh, releasing convicted extremists without putting them through deradicalisation programmes may have terrible consequences. “We will read about them in the paper because they went off,” he says. “It seems that we only want to wait until [a terrorist attack] happens and then react, and then it’s too late.”