The age of the image has gone. The Arab Spring has produced historic moments but, as yet, few defining images. Across the 20th century, the first century of popular photography, there have been images that stand apart, that are central to our understanding of momentous events. Indeed, these images define those events. The best example, probably the most easily recognised news photograph of the last century, is the lone protester, standing before the tanks as they roll towards Tiananmen Square.

These photographs capture a singular moment in time. But now, in the age of 24-hour news channels and ubiquitous cameras and camera phones, we don't remember a moment in time, we remember an event.

Take a recent example. September 11, 2001 in New York. Most people have a memory of various moments from that day: the planes hitting the towers, the towers on fire, burning above New York, and the eventual collapse, coating the city in dust. The sequence is well-known and often replayed. But there is no one image, merely a collection of images.

The next day, newspaper front pages around the world tell this story. The most reproduced moment is the fireball created as the second plane hit the towers. But even that is not one image, but a sequence, or, rather, a moment that lasted a few seconds, photographed many times from many angles, each subtly different. It is an event, not an image.

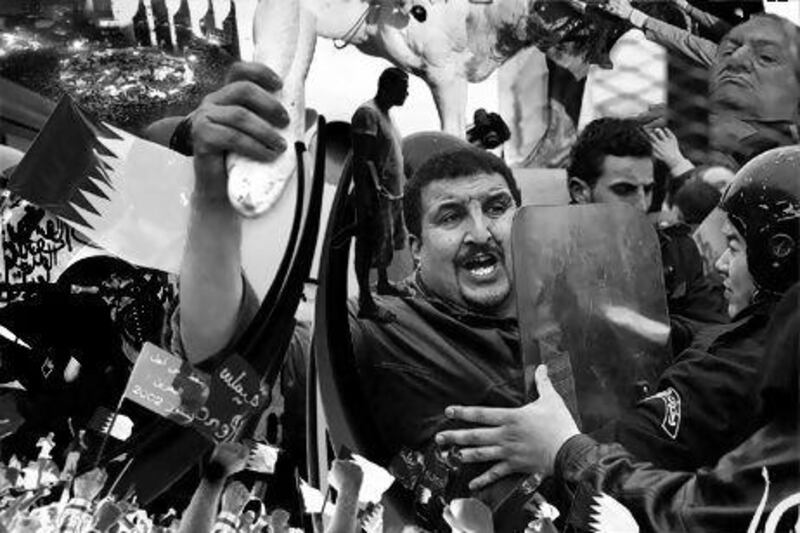

This is also the case with the Arab Spring. The astonishing images that came out of Tunisia, and then Egypt, Libya and Yemen are not single images but events. The crowds in Tahrir Square, the most easily recognisable gathering of the uprisings, form an event, of which many images have been taken. But there is not one iconic image.

In Libya, we think of the months of fighting, but there isn't one image that defines the revolution. There are some that have become very well known - such as the amusing photograph of a brave man playing the guitar while rebels fight Qaddafi's troops, an image that went viral; or perhaps the gruesome final grainy footage of Qaddafi himself, shot on a camera phone. Or in Yemen, the enormous crowds of people, holding long flags of the nation, braving the bullets of Saleh's regime. But there is not one image that defines either revolution.

Indeed, there are no verified images of the single most important moment of the Arab Spring, the self-immolation of Mohammed Bouazizi, the Tunisian man who sparked the uprisings of the Arab world.

This lack of images is partly a function of the revolutions themselves: a leaderless mass uprising, without a face on which to hang the whole story.

The sheer number of people in the crowds, or the rapid back-and-forth fighting on the long road from Benghazi, or the shattering of Homs and Hama in Syria, made it necessarily difficult to capture moments that, pulled out of the narrow instant of history, would have wide resonance. The crowds in Tunisia, Egypt and Yemen meant that photographers and videographers were rarely in the same place, watching different moments unfold.

Some of the most iconic events are not captured particularly artistically, but because they represent such momentous moments, they stand apart. The photographs of Hosni Mubarak in court, facing trial by his own people, is an image that stays with me. As someone who has spent so much time in Egypt and in the Middle East, who has seen first hand the repression of some of these governments, seeing the leader of the Arab world's largest country toppled and then tried by his own people was incredibly moving.

And there are some iconic moments that cannot be captured in a photograph. Watch the last speech given by Nicolae Ceausescu as he addresses a crowd in Bucharest in 1989, and there is a moment, as the crowd refuses to be quiet, where he looks bewildered. It lasts for maybe two seconds, but in that hesitancy, we feel we see the end of his brutal regime. The Romanian people are no longer afraid. Ceausescu was tried and shot dead two days later. In a similar way, footage may yet emerge of Mubarak or Ben Ali being told to go, or of Qaddafi leaving his compound in Tripoli for the last time to run from his own people.

There may yet be an iconic image of the revolutions, an image that, in 10 or 20 years, will define our memory of this tumultuous time. That image, if it comes, will probably come from the Syrian uprising, which is still ongoing.

The lack of a single defining image of the Arab Spring tells you much about the way we now consume media and understand the world around us. But it also tells you much about the Arab Spring, about this astonishing uprising of human beings that, even without a single image, remains iconic.

Faisal Al Yafai is a columnist for The National.