CASABLANCA // Ten years ago, Jewish fathers in Morocco looked at demographics and decided it was time to build a museum. Morocco's once-thriving Jewish community has shrunk to a handful since the creation of Israel in 1948. Today, Simon Levy, a linguist and historian, fights doggedly to preserve its memory as director of the Arab world's only Jewish museum.

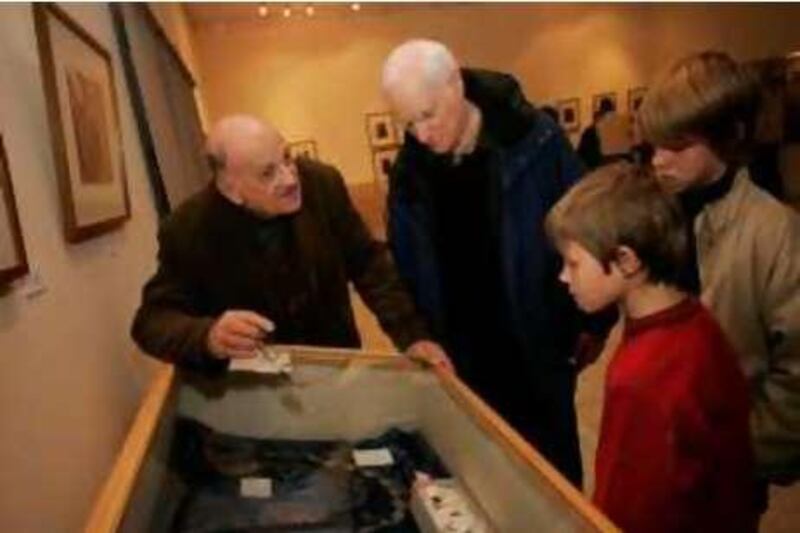

Mr Levy recently played host to a group of high school students. For most, it was their first exposure to Jewish Morocco. While Mr Levy normally sees a trickle of foreign Jewish tourists, his target audience are Muslim youngsters. "More than anything, I want them to learn that there's a different way of being Moroccan," Mr Levy said. The Jewish Museum of Casablanca is a complex of low, white buildings with gardens of cactus and palm trees. Inside is a collection of artefacts from traditional Jewish life, plus an archive of photos, documents and films. For Mr Levy, the museum stands as testament to a rich Jewish life in Morocco even as the country's dwindling community flickers at the edge of existence.

Mr Levy walks the students through the galleries, explaining the Torah scrolls, silver jewellery, and photos of Jewish life - rabbis with long beards, boys in yarmulkes poring over Hebrew texts, menorahs blazing in the synagogues. He asks the students to identify the Jews and Muslims in an old photograph. They guess unsuccessfully for a moment, then Mr Levy asks what the picture represents. "Mixing?" a girl said.

"No!" Levy said. "Because they are the same." Jews and Muslims share many customs that mark them as Moroccans, Mr Levy tells the students. They speak Moroccan Arabic, eat couscous and tajines, drink green tea laced with mint and make pilgrimages to the shrines of local Jewish and Muslim saints. It is the result of nearly two millennia of Jewish presence in Morocco that has withstood successive upheavals.

Nearly 2000 years ago, Rome destroyed the Temple of Jerusalem and drove the Jews into exile. Some did not stop until they reached Morocco, where they quietly flourished through Roman, Vandal and Byzantine rule. Arab armies barrelled into North Africa in the seventh century, bringing Islam and imposing the second-class status of dhimmi on Jews. In the 12th century, the Almohad dynasty went further, ordering Jews to become Muslims or quit Morocco. Most converted falsely until the Almohads fell in the next century.

By now, Morocco was home. Jews were prominent in metal-working, banking and commerce, and increasingly served Moroccan sultans as middlemen to Europe. The community was bolstered in the 16th century by Jews fleeing waves of persecution in Europe. Jews also suffered in Morocco at moments of political tension. European visitors wrote of Jews forced to walk barefoot near mosques, cheated in courts and assaulted with impunity.

Twentieth-century French colonialism abolished the dhimmi status, but replaced it after 1940 with the repressive decrees of wartime France's pro-Nazi Vichy government. The appeal of Zionism to Morocco's Jews increased, compounded after the war by economic hardship. After Moroccan independence in 1956, Jews gained full rights as Moroccan citizens and today enjoy freedom of worship and government support for Jewish institutions. But since the creation of Israel in 1948, a Jewish community that once numbered about 265,000 has plummeted to fewer than 2,500.

For some Muslim Moroccans, the dwindling of the Jewish community is a bitter loss. "I had Jewish friends when I was a kid," said Mohamed Ismail, a Moroccan filmmaker who grew up in the 1950s. "Then overnight, they were gone." In February, Mr Ismail released Adieu Meres (Farewell Mothers), the story of Jewish and Muslim friends torn apart by political tension, money troubles and the machinations of an Israeli immigration agent. Subplots feature a Jewish insurance broker who sells his practice to join family in Israel and a doomed Muslim-Jewish romance.

"If it hadn't been for the creation of Israel, the Jews wouldn't have been compelled to leave," Mr Ismail said. Adieu Meres will represent Morocco at the 2009 Academy Awards in the Best Foreign Language Film category. Israel is home to about one million Jews of Moroccan origin. But nowadays Morocco's few remaining Jews are heading North, not East. "For most Jews, Morocco no longer offers possibilities," said Shimon Cohen, the headmaster of Casablanca's Lycée Maimonide, one of four Jewish schools in Morocco. Armed with French diplomas, Mr Cohen's students go on to university studies and jobs in France.

But Mr Levy, the museum director, insists that despite their emigration, "the millions of Moroccan Jews wandering the earth remain attached to their country". At the museum, Mr Levy and the visiting students are winding up their tour. He leads them into a small synagogue and his assistant brings everyone glasses of Moroccan green tea. "It's a surprise to learn that Jews and Muslims lived in harmony," said Zina, 14, one of the students. "Before, I had only the image of Israel and the Palestinians fighting one another."

Mr Levy points to a drawing on the wall depicting Jerusalem. The Dome of the Rock, Wailing Wall and Al Aqsa Mosque are all visible. "What do you think this picture represents?" he asks the students. "Peace?" says a boy. "Yes, peace." jthorne@thenational.ae