BAGHDAD // Built to protect residents from the car bombs and suicide attacks that rock the city, the concrete blast walls have now taken over. They cause traffic jams, divide neighbourhoods and serve as a constant reminder of life under occupation. These days, however, they also provide hope.

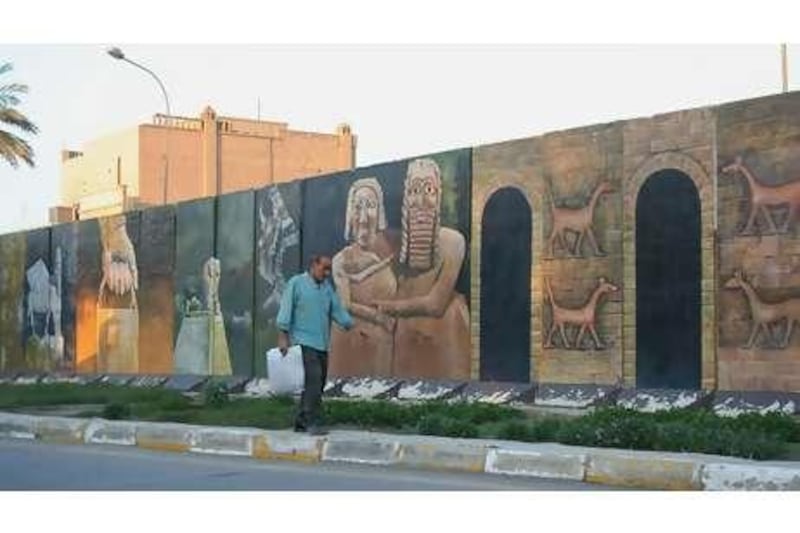

While Paris has the Mona Lisa and Rome the Birth Of Venus, Baghdad's beleaguered artists are creating their own visual icons out of the walls. On Abu Nawoz Street, a prime piece of real estate that lines the River Tigris, artists have created a visual history of Iraq. Paintings of the Gates of Ishtar, the Kingdom of Babylon, Lions and ancient Kings and Queens have been added to the most unlikely of canvasses.

"The idea is to give Baghdad life and colour, to put a beautiful view against this grey picture of violence," said Asaad Yousif al Saghir, an artist and teacher at the College of Fine Art in Baghdad. It is his students who have been dispatched across the capital to beautify the city. The Abu Nawoz scene is his work of art and one he is proud of. "The idea is to give Baghdad life, colour," he said.

Mr al Saghir, 36, was quick not to claim credit though. "The idea, it was not an Iraqi idea. There are a lot of examples, the Berlin Wall, between West and East Germany, for example." Despite borrowing the idea, the wall art in Iraq has a special purpose. "Let me tell you, frankly we chose special places to show the opposite of life during the looting, kidnapping and killing. To show there is an opposite way to show how deep Iraqi history is," Mr al Saghir said.

His piece on Abu Nawoz Street is outside the French Cultural centre; his hope is that it will show foreigners the history of Iraq and that by being in such a prominent location will attract media interest so the outside world will also see. Jamal, a security guard who works near the wall, said he liked it. "We believe it is not a wall, it is like a painting. People come and look and ask what it is and we tell them, this is Babel."

To understand the importance of the art, which has been springing up all over Baghdad for the past 18 months, one must first understand how hated the blast walls are. "When I see these walls, I feel they are going to fall on me, I feel suffocated," Mr al Saghir said. Shaddad al Qhar, an Iraqi artist who has exhibited his work in Europe and whose paintings sell for thousands of dollars, echoes this sentiment. "For sure, positive, I don't like it. You feel like you are yourself in a military camp."

The walls have also had a crippling effect on some local enterprises. Ahmad Fathel, a 36-year-old restaurant owner, has seen his business drop after walls were erected around his premises. "These walls separate my restaurant from the main street, and it costs me a lot of money. I hope one morning I will go to work and I will see these walls removed," he said. Mr Fathel used a famous Iraqi saying to express is his anger, the gist being that it is better to have your head chopped off than lose profit.

Despite the negatives there is no doubt that when suicide bombings and sectarian killings were rocking the capital, the walls served a purpose. Even today, they provide a vital barrier against bomb attacks that hit the city on an almost daily basis. Lames, 42, the owner of a beauty salon who uses only one name, agreed. "The concrete walls protect my shop. Some people are trying to affect my business and my customers and I feel protected [by the blast walls]."

Perhaps the harshest judges of the walls are those among the Baghdad art community. "This is not professional, it is just a hobby," Mr al Qhar said. "This is not representing Iraqi culture. I believe it is good to cover the walls but I hope you won't say this is Iraqi art." The National