Thousands of Algerians took to the streets on Thursday to protest a presidential election they see as illegitimate, clashing with police and urging the country to boycott a vote that is likely to go to a second round.

Early results on Thursday night showed no candidate was on course to get the 50 per cent of votes needed to win outright. It was not yet clear when the run-off between the two top-placed candidates would be held, although it is expected to be between December 31 and January 9.

The electoral authority said the results of Thursday's vote would be released at 11am on Friday.

Election officials said the overall voter turnout was just under 40 per cent – a little over 41 per cent among Algerians voting in the country and close to 9 per cent among voters overseas – the lowest participation rate in a multi-party contest in Algeria's history.

Some of those who voted said they had chosen to spoil their ballot rather than snub the election.

While overseas polling booths opened on Saturday, they were scarcely attended, according to media reports, with 14 per cent of registered voters in the UAE turning out. Expats make up about 20 per cent of Algeria's voting population.

Those who cast their votes on Thursday were labelled traitors by demonstrators, who also referred to the candidates as "five wolves".

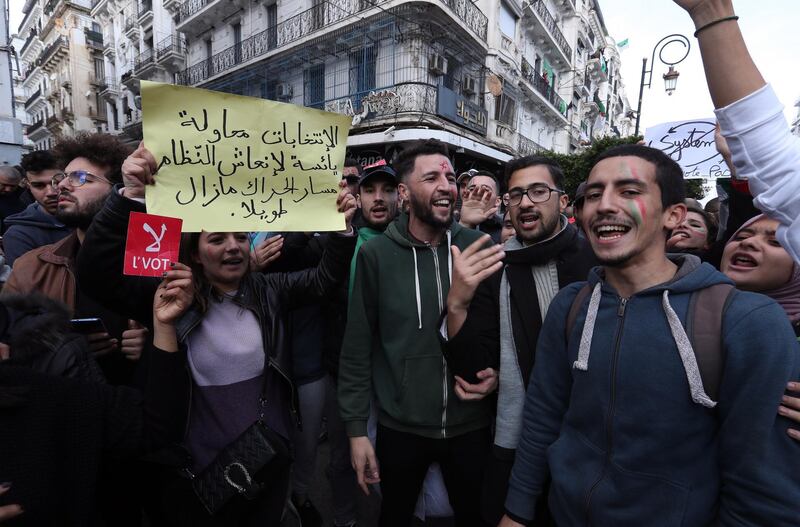

At a march in central Algiers, large groups of mostly young men chanted slogans like "democracy not military" and "generals in the rubbish, then Algeria gets its independence" under the gaze of a circling police helicopter.

Protesters say they reject what they see as a sham vote that is aimed at protecting the interests of the political establishment, and have demanded complete reform of the system.

"I don't believe in the vote, I don't believe in the five candidates. I want to vote and have an election, but not with the government of the 'gang'," said Dr Yusif, who has been part of the movement since the start and abstained from voting.

"They say that Algeria is a democracy, but it's just ink on paper – it's not true. It's still a dictatorship ... we will not stop protesting until the country is liberated."

The large protests, known as the Hirak movement after the Arabic word for mobilisation, began in February after long-time leader President Abdelaziz Bouteflika announced he was to stand for fifth term, in contravention of the constitution. Within six weeks he had been forced to resign.

However, the unrest has continued and the five men running for president, who protesters refer to as the gang, either supported Mr Bouteflika or participated in his government.

Lt Gen Ahmed Gaed Salah, who triggered the legislature that forced the 82-year-old Mr Bouteflika to step down due to ill health and has since become the country's most powerful political player, pushed for the vote as the only way to end the crisis. The conviction of two former prime ministers on corruption charges earlier this week was seen as an attempt to show the public that the government was willing and able to reform.

Although the protests have remained deliberately peaceful over the last nine months, Red Crescent volunteers said they had started to see injuries caused by clashes with police since Wednesday.

The National witnessed a young man being stretchered into an ambulance after sustaining a head wound he claimed was caused by a police baton, causing sight problems. Protesters also said they had seen police use unnecessary force on people that had resulted in injury.

While political and civil organisations urged people to refrain from voting, some chose to sabotage polling stations. A video circulated online appeared to show protesters raid an election official at a local school in the province of Bejaia, known for its Amazigh (or Berber) population, seizing ballot boxes and scattering votes across the playground.

Former Minister of Culture Azeddine Mihoubi had been seen as the favourite, with former prime minister Majid Tebboun close behind.

Ali Benflis, another former prime minister and presidential candidate, promised that if elected he would engage with opponents of the vote during Algeria's first political debate earlier in the week.

Who are the protesters and what do they want?

The Hirak movement, named after the Arabic word for mobilisation, grew out of the weekly protests that began in February by the announcement that Mr Bouteflika was to stand for a fifth term.

Had he been successful it would have breached constitutional limits to presidential mandates. He had been almost completely absent from public life after suffering a stroke in 2013.

Protesters seek political reform in a country where almost 50 per cent of the population is under 30, but is dominated by men over 50.

To a lesser level, the protests also demanded improvements to infrastructure, housing and the jobs market.

The Algerian demonstrations have been peaceful, avoiding the bloodshed seen recently in Iraq and skirmishes in Lebanon.

But scores have been arrested, including journalists and opposition figures.

Thousands of mostly protesters take to the streets every Friday after prayers, and on Tuesdays students take to the street.

While some praise the military for punitive actions against high-ranking officials, others say it is propping up the ruling elite.

On November 1, for the 65th anniversary of independence from France, millions took to the streets likening their struggle to the historic fight for freedom from their former colonial ruler.