CAIRO // Just over a year ago, Amira Maurice was attending a New Year's Eve Mass in the Saints Church in Alexandria with her parents and fiance, their marriage set for a few months away. Then the bomb blast ripped through the church.

Now, Ms Maurice, 28, a pharmacist, is in Germany undergoing a string of surgeries to save her leg and recover from burns. Her fiance is dead, one of the 21 people killed in the suicide bombing at the church.

Another New Year's has passed since, and there are still no answers in Egypt's most dramatic attack on Christians. The investigation was halted 11 months ago. The only suspects ever detained were released, and it is not clear they had any role in the bombing. No new suspects have ever been named.

"Nothing. Nothing at all has happened with the investigation," said Ms Maurice's father, Nabil Roman. "It is ridiculous."

Mr Roman suspects that the interior ministry has dragged its feet in going after the case, but he does not know why.

"Something is not clear. All I can say is that God will deal with them."

The attack was soon overshadowed by the uprising that led to Hosni Mubarak's toppling on February 11. But the failure to answer who was behind the blast has fuelled resentment among Egypt's Christian minority. This sentiment has bred conspiracy theories.

The failure has also highlighted the deep problems that ailed Egypt's police forces during Mr Mubarak's nearly 30-year rule and only worsened after his fall.

Police were notorious for failing to investigate crimes - instead, their modus operandi was usually to detain possible suspects and torture them into confessions, according to rights groups and former police officials. After the fall of Mr Mubarak's regime, the police have been in disarray and have resisted reform in their ranks.

An interior ministry official said the delay in investigating the bombing was because of the turmoil after Mubarak's regime ended, and the inability of police to arrest and interrogate people like before.

Egypt's security forces long had near unlimited power to arrest people under emergency laws. The laws are still in place, but police have become more hesitant to use them in some cases for fear of eventual retribution.

Joseph Malak, the chief lawyer for families who lost relatives in the attack, said he has been pressing the chief prosecutor's office for months to proceed with an investigation, but prosecutors are legally bound to wait for the interior ministry to hand over its initial findings, which it never has. This has left the case in limbo.

He said he does not know why the case is still with the police.

The rights activist, Hossam Bahgat, said the interior ministry "has been and remains broken".

"It is not just abuse and corruption, but also inefficiency," said Mr Bahgat, the head of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights. Under Mr Mubarak, police had more of a role in monitoring opponents and preserving the regime than investigating crime, and that "had a detrimental effect", he said.

He said no suspects were ever tried in two of Egypt's previous most prominent terror attacks - suicide bombings in Sharm El Sheikh in 2005 and Dahab in 2006. In the 2004 bombing of another resort, Taba, three men were sentenced to death, but Mr Bahgat said it was "abundantly clear" they had confessed under torture.

The investigation into the church bombing appears to have been marred by the same methods. One man who was detained died in custody after witnesses said he was tortured. Police claim his death is being investigated.

Police arrested about 40 men after the Saints Church bombing, all of whom had been previously detained in 2006 for alleged ties to militants in Iraq, although none were charged at the time and none were subsequently charged in the church bombing. Most belonged to the Islamic Salafi movement.

The men were all released in April when the military, which took power after Mr Mubarak's fall, released political prisoners.

Several of those detained said they were tortured during detention.

"We were arrested for being arrested before. We had done nothing wrong, but that never mattered under Mubarak," said one of the former suspects. "We want this case solved more than anyone because it's our right to know who did this and who tried to blame us for it."

Ahmed Amin, a lawyer who was detained in connection with the attack, said police told the detainees to fabricate scenarios of how the attack was planned. "The officers interrogating us told us we either accept this case nicely or they will force it on us."

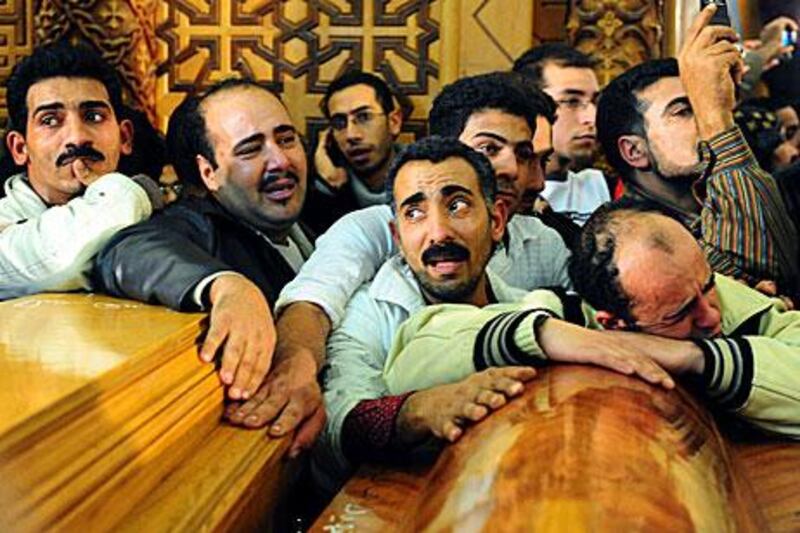

Last week, several hundred protesters - most of them Coptic Christians - held a vigil outside Cairo's main courthouse to remember the victims of the attack. Some held posters demanding the resignation of the attorney general and others demanded Habib El Adly, the interior minister at the time, be investigated as a suspect.

Mr Roman is among those who suspects El Adly had a role and he feels justice has been served, in a way, with the trial of Mr Mubarak and El Adly on charges of complicity in the killing of more than 800 protesters in last year's revolt.

"God got us our justice and more when the revolt happened on January 25 and all these men went to jail," he said. "God stood with us."