NEW DELHI // When Archana Shekhar saw a widely-circulated photograph of students’ friends and family scaling the outer walls of a school to help them cheat, she laughed.

“I mean, what was happening was ridiculous, of course,” she said of the photo, taken during grade 10 and grade 12 exams in Bihar on Wednesday. “Exams have to be free and fair, and this kind of cheating has to be cut out.”

But as a grade 11 high school student in the southern India city of Mysore, she also felt a pang of empathy. The tense, nervous atmosphere around such exams was only too familiar to her.

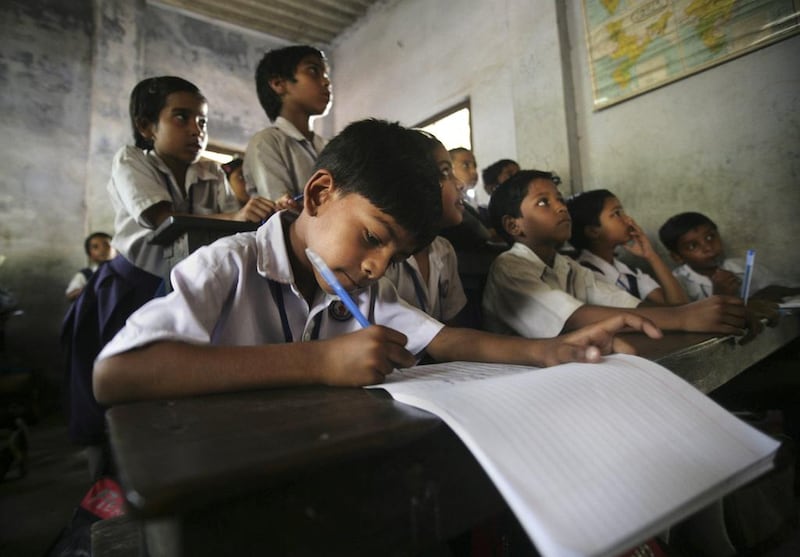

Across India, students worry that if they don’t perform well on the exams, their future will be plunged into uncertainty. Prospects of higher education, and therefore of well-paying jobs, might fade, and families left disappointed.

Every year, more than 20 million students, aged between 16 and 18, enter the final year of high school – Grade 12 – in India. All hope to score highly enough during their leaving exams to earn a place in one of the country’s 640-odd universities.

“Even if you assume 20,000 seats per university, which is hardly the case, we’re nowhere near that [20 million] figure,” Narayanan Ramaswamy, the Chennai-based head of the education advisory at KPMG India.

Within these universities, there is a vast gap between the top-tier institutions and the rest.

This makes the struggle to get into the very best universities even more difficult. At the same time, the government is trying to increase the number of high-school graduates, even though “there aren’t enough universities to take them all in,” Mr Ramaswamy said.

[ Indian relatives scale school walls to help puils cheat ]

For instance, the annual admission rate for the 16 elite Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), which are scattered across India, is lower than two per cent – out of the approximately 500,000 applicants who apply every year.

The IITs hold their own gruelling entrance exams, while other universities, which depend on marks from high school final exams to screen their applicants, can set dizzying qualification criteria. Two years ago, the Shri Ram College of Commerce in New Delhi mandated that students who had not studied commerce-related subjects would have to show exam marks of 100 per cent to earn a seat in its Bachelor of Commerce degree programme.

“The cut-off [marks] may have been perceived as unrealistic,” PC Jain, the principal of the college, said at the time. “But the rate at which these seats got filled up and the number of students who are still turning up for admission indicates that our cut-offs were actually a little low.”

All this makes the pressure to perform well immense. For poor families, who have pinned their hopes for economic and social advancement on their children’s academic performance, the burden of anxiety is even heavier. Every year, between the start of the exam season in March and the release of results in May or June, newspapers fill up with the tragic news of student suicides.

Last Wednesday, a 17-year-old girl in Chennai committed suicide before a mathematics exam. She had been worried about her performance, her parents told the Times of India newspaper. Early on the morning of the exam, she locked her room, ostensibly to study, and hanged herself from a ceiling fan.

In 2013, the most recent year for which statistics are available, 2,471 students committed suicide, up from 2,246 in 2012, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

Although it is not always possible to attribute such suicides to academic pressures, the highly competitive nature of high schools in India are thought to debilitate the mental health of students.

For nearly two decades, the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), a body that runs schools affiliated with the federal government, has organised counselling for students suffering from exam-related stress.

Parents and students can dial into toll-free numbers to talk to mental health counsellors. At schools, and on its website, the CBSE also screens two short films, “Smile Through Stress” and “Exam Stress: A Natural Feeling.”

ssubramanian@thenational.ae