ISTANBUL // Abdul Aziz Al Kheir, a medical doctor and leading Syrian dissident, was driving home from Damascus International Airport a year ago when his car was stopped at a government checkpoint.

He, and two other political activists travelling with him, have not been seen or heard from since.

In many ways the case is not unusual. According to human-rights monitors, more than 10,000 Syrians have “disappeared” since the start of the uprising in March 2011, taken by the mukhabarat, feared secret police agencies that enforce regime control.

Witnesses saw them taken away by air-force security on the main airport motorway but there has been no confirmation they are in regime hands and they have not been charged with any crime.

Shortly after Dr Al Kheir disappeared on September 20, 2012, regime officials said armed rebels abducted him, a claim disputed by Dr Al Kheir’s friends, who drove through the checkpoint before him and watched as he was detained by air-force security.

Opposition activists say they believe he is still alive, and the regime does not want him dead. Like the Syrian president Bashar Al Assad, and much of Syria’s ruling elite, Dr Al Kheir is from the Alawite sect.

In this respect, his disappearance is different from most other cases.

Dr Al Kheir, who had served 14 years in a regime prison between 1992 and 2006 for peaceful political dissent, was returning from meetings in Moscow and Beijing when he was detained.

He had been seeking to convince Russia and China to drop support for Mr Al Assad, or at least use their influence to rein him in and push for a political transition.

Although a member of the National Coordination Committee, a domestic opposition group broadly tolerated by the regime, Dr Al Kheir’s trip to Moscow and Beijing appears to have crossed the boundary of what the authorities were prepared to accept.

“Because he is Alawite and from a strong family, the regime decided to kidnap him – possibly they will not kill him, they might use him as a bargaining chip at some point,” said Zaidoun Al Zaubi, a dissident and friend of Dr Al Kheir.

“He has a great deal of knowledge, deep experience of Syrian politics, a sharp mind and was unquestionably a Syrian nationalist, so the regime feared him.”

A routine of torture

Many prisoners are kept in a shadowy network of squalid detention centres, in which torture is routine and death commonplace, former inmates say.

Because the mukhabarat operates outside of any written laws, family members are not always notified if someone is taken into detention. Instead, informal contacts and back channels that allow family and friends to make contact with the secret police are often used to try to locate prisoners.

Bribes are frequently paid for scraps of information, which may or may not be accurate, according to Syrians who have been involved in tracking down friends and loved ones held in a labyrinthine detention system overseen by more than a dozen independent security branches.

“You make a lot of phone calls, you try to find out where people were arrested and then which security unit was working in that area at the time, and then you might be able to find some [mukhabarat] officer who’ll tell you if they are holding the person or not,” said an opposition organiser who has spent time in jail, and helped locate other political prisoners.

Sometimes, with the right connections and enough cash, bribes can be paid to lose files and release detainees.

A former inmate of the political security branch in Damascus said his family paid US$10,000 (Dh36,700) to have his case file “lost” by a senior officer, who was then able to arrange for the prisoner’s release – on condition he leave the country immediately and never come back.

“My family paid without me knowing,” the former prisoner said. “We had a friend who knew someone high up in political security so they could make the arrangements.”

He remains inside Syria and is wanted for helping get humanitarian supplies, including food, fuel and medicine, to rebel held areas.

During detention he was hung from the ceiling by one leg for hours, until he vomited or fainted. Weeks after being freed, his left leg was still covered in fierce purple bruising from the clamp that had been used to suspend him.

It was his second time in detention since the uprising began, and his family was convinced he would not be lucky enough to be freed again.

“I was angry with them for paying all that money, but they said it was cheap because it kept me alive.”

A UN panel, which asked about allegations of thousands of disappearances this year, said the regime responded that “there were no such cases in Syria”, with all arrests were carried out legally.

The Violations Documentation Centre, a human-rights group working inside Syria, led by the lawyer Razan Zaytouna, released a report this month detailing the experiences of five men held for between one and two years by air force intelligence, in Harasta, eastern Damascus.

In gruesome detail the men describe abuse by doctors tasked with keeping them alive through brutal interrogation sessions, starvation conditions in crowded basement dungeons, summary executions and death from disease and torture.

The centre has documented the deaths of more than 3,000 prisoners in mukhabarat cells since the start of the uprising. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have also recorded hundreds of cases prisoners dying in custody.

Prisoners can languish in detention cells for months. Some are freed, others are charged with crimes and transferred to prisons such as Adra and Sednaya.

Dissidents who have spent time in both the mukhabarat holding cells and the squalid, overcrowded state prisons describe a sense of relief at leaving the secret police behind.

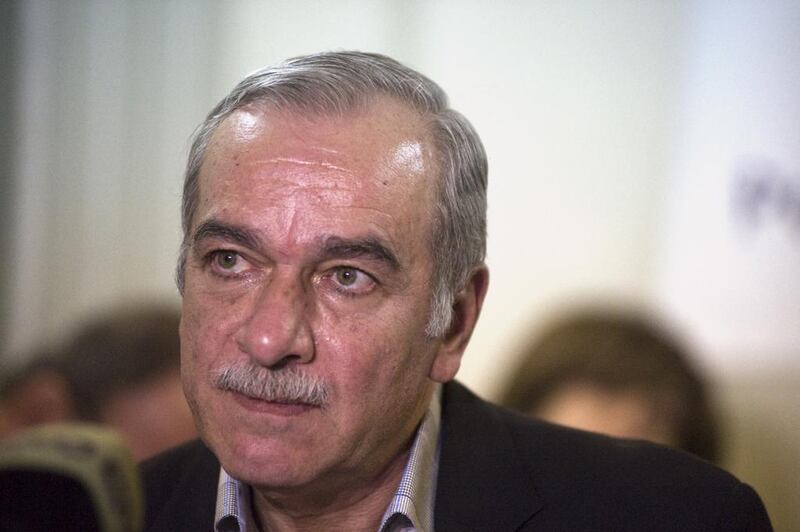

“We used to know the new people who were being transferred in from the mukhabarat because they would still be bleeding and have broken bones or gunshot wounds,” said Kamal Labwani, a former political prisoner who served 10 years in jail for dissent before being freed in November 2011.

“They would sit on the ground and when they stood up, there would be a pool of blood on the floor, they hadn’t been given any proper medical treatment by the mukhabarat – you really can’t compare prison with the detention centres, prison is a luxury compared to that.”

psands@thenational.ae