ISTANBUL // In a sign of a new willingness to come to terms with the more difficult chapters of its recent past, Turkey has decided to restore citizenship to Nazim Hikmet, one of the country's greatest poets, almost half a century after he died in exile.

"We think we have done the right thing," Cemil Cicek, the deputy prime minister and government spokesman, told reporters after the decision by the government in a cabinet meeting in Ankara this week. Hikmet will regain his Turkish citizenship posthumously as soon as the ministers' decision is published in Turkey's Official Gazette. The decision carries enormous significance for a state that has often found it hard to admit and correct mistakes. The move follows a series of other recent steps that the government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the prime minister, under pressure at home and by the EU to do more for Turkey's bid to join the European Union, has taken to demonstrate its commitment to tolerance and reform.

In October, Mehmet Ali Sahin, the justice minister, made history by becoming the first leading Turkish politician to publicly apologise for the death of a torture victim. Last month, the government agreed in general to grant more rights to the Alevis, a liberal Muslim minority. A week ago, Turkey's first state-run Kurdish television station went on the air. "Nice gestures have been made by the state lately," columnist Hasan Cemal wrote in the daily Milliyet. But few things the government has done recently matched the symbolism of Turkey officially welcoming Hikmet, a titan of literature who was stripped of his citizenship in 1951 and considered a traitor for decades, back into the fold. Hikmet's poetry was banned in Turkey until 1965. Mr Cemal praised the cabinet decision as "an apology after 58 years". Many other writers and intellectuals agreed. "It was long overdue, but it is an important decision, one that many governments in the past were unable to take," said Kiymet Coskun, the deputy president of the Nazim Hikmet Culture and Art Foundation in Istanbul.

Over the decades, admirers of Hikmet had tried several times to have him rehabilitated, but all attempts failed. In 2000, a small left-wing party collected 500,000 signatures for a petition that called on Turkey to rehabilitate Hikmet and bring his remains back to Turkey, but the government did not act upon it. As recently as 2001, Enis Oksuz, a minister at the time, said he would not sign a degree to give Turkish citizenship back "to a man who insulted my country, [Turkey's founder Mustafa Kemal] Ataturk, the Turkish army".

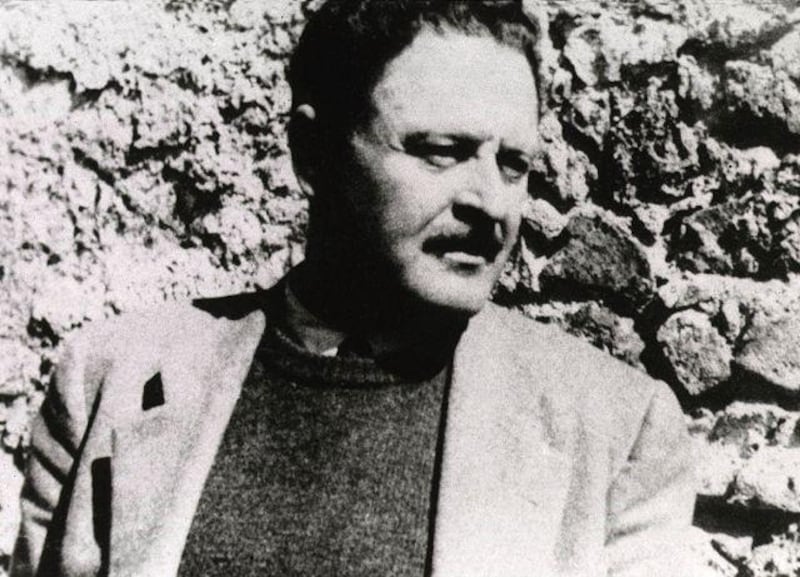

Hikmet, who was born in 1902, was in trouble with Turkish authorities for much of his adult life until he left the country for good in 1951. A dedicated communist in a newly founded republic that saw communism as a threat, Hikmet was prosecuted several times. In 1938, he was sentenced to 28 years in prison for inciting mutiny in the navy. Shortly after his release in a general amnesty in 1950 he fled to Moscow, where he died and was buried in 1963.

During his years in exile, Hikmet wrote poems that spoke of his love for his Turkish homeland and of his homesickness. In one famous poem, he wrote that he wanted to be buried in an Anatolian village cemetery under a tree. Turks are moved by Hikmet's writings even today. "In the hearts of the Turks, he always remained a Turk", despite being stripped of his citizenship, Ms Coskun said. Even today's ministers are said to have been touched by Hikmet's poetry. The Hurriyet newspaper reported that Ertugrul Gunay, the culture minister, who led the campaign to rehabilitate Hikmet in the government, read Hikmet's poem My Homeland to his cabinet colleagues in the meeting this week. After hearing the poem, ministers signed the decree for Hikmet, the newspaper reported. Mr Gunay told Turkish media afterwards the cabinet meeting had marked "one of the most emotional moments" of his time in office.

"Turkey did what should have been done years ago," the minister said, according to Turkey's state television TRT. He called Hikmet "Turkey's greatest poet". The minister also said the government's willingness to make peace with prodigal sons among the country's intellectuals did not stop with Hikmet. Newspapers reported that Yilmaz Guney, a controversial filmmaker who fled Turkey in 1981, was stripped of his citizenship in 1983 and died in Paris one year later, was also due to be rehabilitated. Guney won the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 1982 and is considered one of the most important Turkish film makers.

"If there are problems with Yilmaz Guney's citizenship, we will correct them," Mr Gunay said. "The prime minister is very determined to break taboos and lift bans. That is also true for Guney's case." Despite the government's stated willingness to bring Hikmet's remains back from Moscow to Turkey, in line with the poet's wish, it is unlikely to happen. Members of Hikmet's family said in newspaper interviews they wanted his grave to remain on Moscow's Novodevichy Cemetery. Several famous writers and artists, among them the poet and playwright Vladimir Mayakovsky who had a strong influence on Hikmet, are buried there.

tseibert@thenational.ae