For generations the port city of Mersin on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast has prided itself as a colourful reflection of Turkey’s cultural diversity, with a mixed Turkish, Kurdish and Arabic population.

Now, the city, which lies to the east of the popular holiday resort of Antalya, is struggling to retain this spirit of tolerance as the arrival of refugees from Syria means competition for scarce resources and limited public services create new divisions while Turkey faces an economic downturn.

Part of the central neighbourhood of Akdeniz has become “Little Damascus” to many locals and, although they were largely sympathetic to the new arrivals when they first moved in, Syrians are often now regarded as an unwelcome addition.

“Fifteen years ago this place was doing well but now it’s crashed,” said 63-year-old Dogan Gul as he gestured around his small grocery shop in the heart of Akdeniz.

“The Syrians don’t come here. They use their own shops and the big supermarkets because the government gives them cards they can use there for free [goods]. I have Arab background myself, but these Syrians are not like us, they don’t integrate. Relations are not good and when the economy gets worse, relations with the Syrians will get worse as well.”

Tension between locals and refugees has already broken into violence. Two years ago, the Adanalioglu district on the outskirts of Mersin was the scene of rioting between Syrians and locals that left dozens injured and forced the authorities to temporarily relocate refugee families.

This atmosphere, as well as rising rents that many locals blame on the arrival of Syrians, has resulted in many of Akdeniz’s original residents moving out of the neighbourhood.

“In the past, the most expensive house in this neighbourhood was 900 Turkish liras [Dh955] a month but now that’s the price for the cheapest,” said estate agent Hatice Celikbas.

“The Syrians live in better conditions than most Turkish citizens. I would say 40 per cent of people have left the neighbourhood now. If you look in the street there are hardly any Turks left. This country has been damaged by these people.”

In the workplace, Syrian newcomers have largely been pitted against Kurds in competition for low-income jobs in sectors such as agriculture and construction.

“Syrians are used as cheap labour in jobs that Kurds used to do,” said Selim Zuberi, who worked for a refugee charity until it ran out of funding.

“Business owners are just exploiting Syrians the way they used to exploit Kurds and they’re having to pay even less in wages now. They used to pay 100 liras – it’s now 20 or 30 liras for a Syrian worker.”

Canan Yuce, a former city councillor for the leftist pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party, said the refugees had also replaced the Kurdish population in another way – as scapegoats for society’s ills.

“It’s true that unemployment increased for local people because Syrians work for less money and the rents doubled or tripled,” she said. “This is a common problem for Mersin because it’s a place that’s historically a migration destination. But the only thing that changed is that before Kurds were blamed, and now it’s Syrians.”

Most Syrians are reluctant to complain about their treatment at the hands of a country that has accepted about four million refugees, the bulk of whom fled from Syria’s civil war after it erupted in 2011. However, they say a recent crackdown by police on unregistered refugees or those who have broken travel restrictions has affected even those living legitimately.

“Life is good here but the police have caused a lot of problems for us recently,” said Hussein, a Syrian cafe manager. “When I walk to my home a few blocks away, I am always stopped by the police to check my documents. This didn’t happen before.

“Also, if we have a problem and call the police, they don’t come. Instead they fine us for things like people smoking shisha because we can’t afford a licence but if we smoke on the street people get upset.”

Sitting on a plastic garden chair under the cafe’s rattan roof, his colleague Kamil – both men asked for their surnames not to be used for fear of repercussions from the authorities – added: “When the police fine us, they don’t always say what it’s for, they just tell us to sign the papers.

“One time, the police officer got mad at me because I had my hands in my pockets while I was talking to him – he wanted me to stand to attention like a soldier.

“This attitude is very disturbing. I think it is discrimination. We understand this country has its laws and they expect us to obey them. We have all our documents and have fulfilled all the requirements, but still they treat us this way.”

Both men, who are in their 30s and from the northern Syrian city of Aleppo, said they had encountered more hostility since Turkey launched the first of two military operations in Syria in 2016.

“People say that we fled our country and one time a Turkish soldier said to me: "Why are you smoking shisha here while our soldiers are dying in your country”? Hussein said.

“They say we are traitors and that we ran away, but which side should we choose? If we fight for either side we would be killing our brothers.”

Second-hand furniture salesman Halid Mahaley, 32, raised another common complaint among refugees – travel regulations that prevent them leaving the province where they are registered without official permission.

“It’s very difficult to get permission, even to visit relatives in another part of Turkey,” said Mr Mahaley, who arrived from Latakia five years ago. “I want to sell furniture outside Mersin but I can’t because I can’t leave this area.”

Other refugees have established a more settled life in Mersin – a city of about a million inhabitants that has been swelled by the arrival of around 200,000 refugees, according to official figures, although many say the actual figure is much higher.

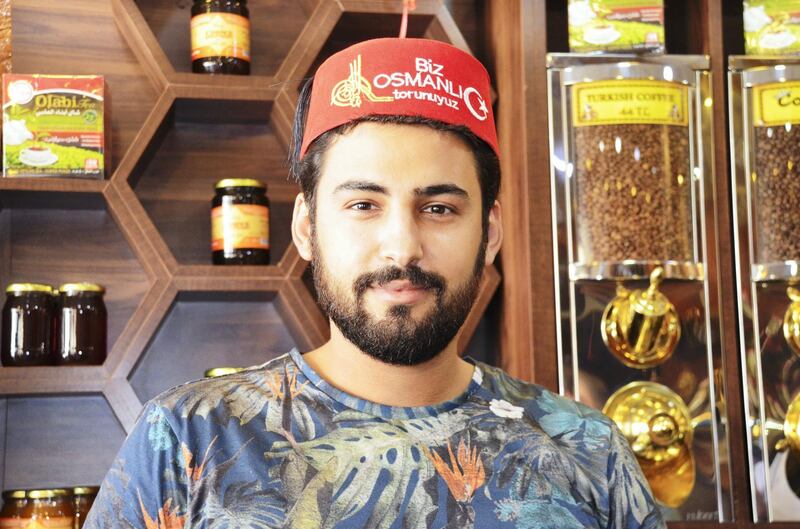

On a busy road in Akdeniz – where most Arabic shop names have now been removed by the authorities following an crackdown on the use of the language – Syrian-owned Olabi Kahvesi sells bespoke coffee blends at prices of up to 66 liras per kilo.

“We have a mix of customers, but mainly Arabs,” said Syrian worker Husam Kiyat, who wore a fez embroidered with the phrase “We are Ottoman grandsons”.

“Our first shop opened in Mersin four years ago and the company has branches in other countries. If the company stays in Turkey then we will stay. We have no problems with the police here.”

However, among locals raising the issue of Syrian refugees often provokes less benevolent anecdotes.

“There are cultural differences between the locals and the Syrians that cause problems,” said Mr Zuberi, the former charity worker. “Syrians like to stay out on the street at night, smoking shisha, and large groups of Syrian men gathering at the beach upsets some people.

“If you are with your girlfriend or family and there are 50 Syrian men next to you it can be intimidating.”

Shopkeeper Mr Gul complained that Syrian businesses had for a long time been allowed to operate without paying taxes or having the correct licences. “The authorities stopped this recently but why were they allowed to do it in the first place,” he said.

With little end in sight for the conflict in Syria and with many refugees having made a life for themselves in Mersin, many fear what the future will bring.

“I worry mostly about the future of Syrian children,” local journalist Soner Aydin said. “Many of them are not going to school or learning Turkish. What will they be doing 10 years from now?

“We are facing a problem that we have helped to create because there was no long-term planning when we took all these refugees in. It’s a problem for us and for them.”