"He was very sick, but who knew there was something so terrible going around?" a Chinese nurse told The New York Times back in 2003, referring to the Sars outbreak that was to kill more than 774 people that year.

Who knew? This is the question at the core of effective public health crisis response, when containing a virus where it starts and informing the public is the best action against it spreading further.

Within the span of less than 20 years, the world has learnt powerful lessons from the 2002 to 2004 the Sars outbreak in southern China and the devastating 2014 to 2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa.

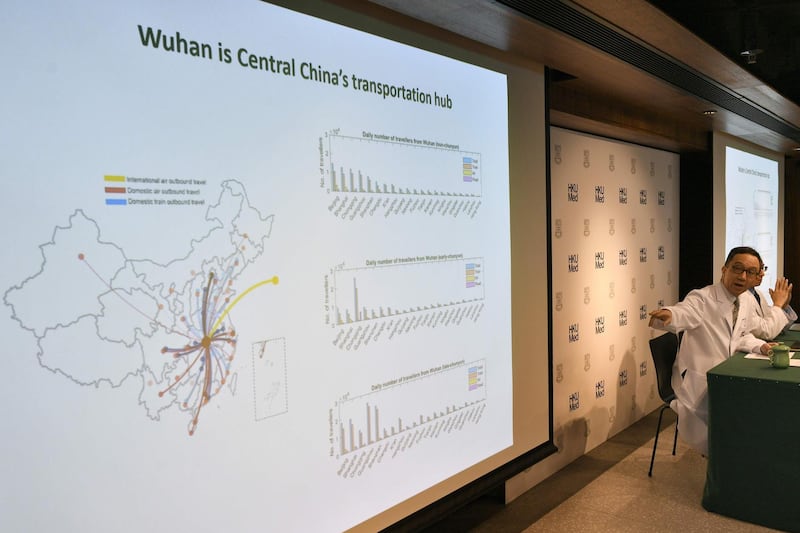

Now a new strain of virus, previously unknown to scientists, has spread across China in recent weeks, as well as to Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Thailand.

So far, the strain has killed four people and 218 cases have been identified, but the true number is thought to be higher.

As another coronavirus grabs headlines, there are several reasons to take heart. Today, information travels exponentially faster and with broader reach than an infectious disease can.

Since confronting Ebola, the World Health Organisation has developed "revolutionary" rapid diagnostics and a blueprint for research and development to find cures more quickly. Major transit points, such as airports and ports, are also working to improve illness detection dragnets.

Since 2016, the WHO, the UN agency working to improve global health, has begun rapid starts to research and development activities during epidemics. For example, in the Democratic Republic of Congo the work of the new R&D team known as "Blueprint" enabled the fast-tracking of effective tests, vaccines and medicines as part of the Ebola response in 2016, the agency said. During that time, it also automated testing for new Ebola cases using a small diagnostic platform called GeneXpert.

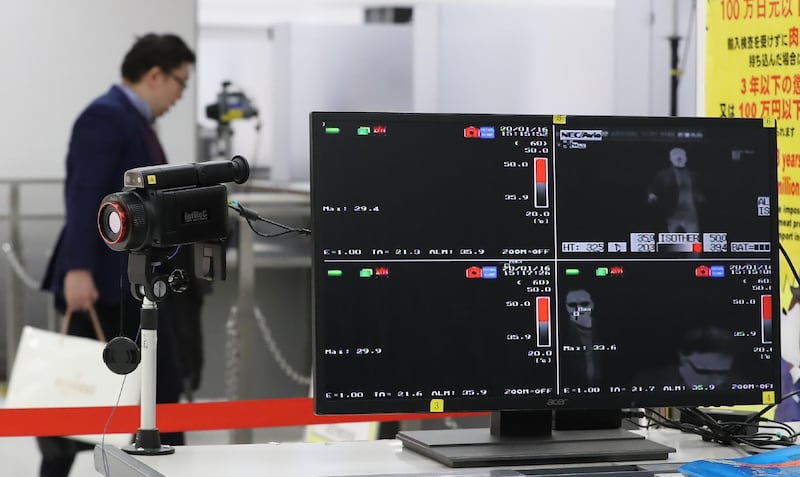

"It's revolutionary," said Pierre Formenty, part of the viral and haemorrhagic fever team in WHO's health emergency programme. "The first and only manual step is for a trained and skilled lab worker to inactivate the sample in a biosafe glove box, which renders it safe to be tested. The sample is then inserted into a cartridge and the rest is automated. A diagnosis can be made in hours," he said this year. While airports currently rely on thermal and infrared cameras to detect the surface temperature of travellers and – with mixed results – identify those with a virus, a team in Leipzig, Germany, has been working for several years to invent a cheap diagnostic tool to test passengers before they board a plane for viruses or respiratory or bacterial infections.

Dr Dirk Kuhlmeier and his colleagues at the Fraunhofer Institute for Cell Immunology and Therapy use a technology already in use by airport security to detect drugs and explosives by swabbing luggage or clothing.

The team is working to develop a system that will do the same but instead will detect different bacteria in human breath and also determine whether bacteria has become drug resistant.

Drug resistance is among the largest global health threats, the UN says, and the pipeline of new antibiotics coming to the market is drying up. It is an area in desperate need of innovation.

"Never has the threat of antimicrobial resistance been more immediate and the need for solutions more urgent," said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of the WHO.

“Numerous initiatives are under way to reduce resistance, but we also need countries and the pharmaceutical industry to step up and contribute with sustainable funding and innovative new medicines.”