KABUL // The assassination of Burhanuddin Rabbani, the former Afghan president and government point man for peace talks with the Taliban, is threatening to bring further instability to Afghanistan as the country grapples with a series of high-level insurgent attacks and assassinations in recent months.

Rabbani, 71, died on Tuesday in his official role as chief of the High Peace Council, a government body tasked last year with spearheading negotiations with the Taliban, after an attacker posing as a reformed Taliban fighter detonated a bomb concealed in his turban while greeting the former president at his home in Kabul.

Mohammad Ismail Qasemyar, the international relations adviser for the peace council, said the bomber, identified as Esmatullah, had approached several council officials, telling them that he was an important figure in the Taliban insurgency and would only speak directly with Rabbani, according to the Associated Press.

On Tuesday, the two met and the attacker went to shake hands with Rabbani, bowing his head near the former president's chest and detonating a bomb hidden in his turban, Mr Qasemyar said.

US and Afghan officials denounced the assassination as a Taliban attempt to thwart peace efforts in the war-wracked country, although the Taliban has not taken responsibility for the attack. But Rabbani, an ethnic Tajik and anti-Taliban commander who presided over years of bloodshed as Afghanistan's president in the 1990s, made little headway in reaching out to insurgents in the past year.

The US, seeking to extricate itself from an increasingly violent and now 10-year-long conflict in Afghanistan, has been pushing for about a year to bring Taliban leaders to the bargaining table. August marked the deadliest month for US troops since the war began, with 81 killed.

US officials provided Rabbani about US$200 million (Dh730m) in funds to coax Taliban fighters away from the insurgency.

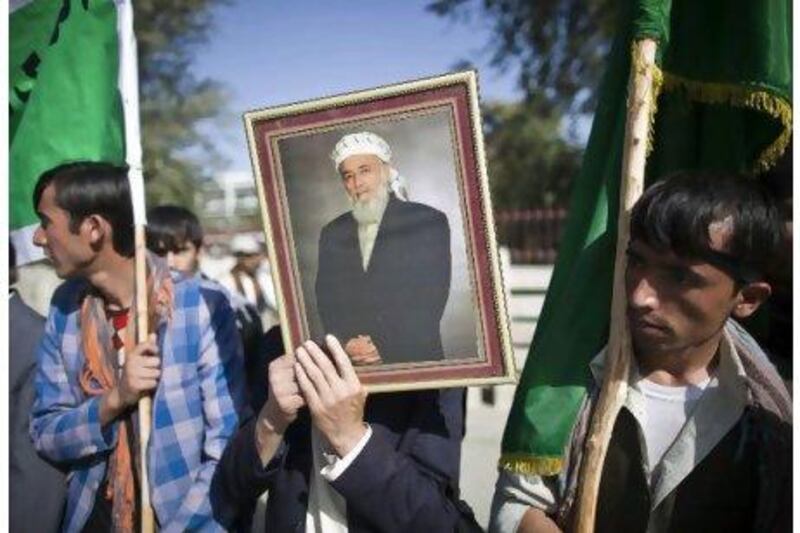

But despite the crowds of mourners streaming to the slain official's house to pay respects yesterday, Rabbani to many was not a peacemaker but an opportunistic warlord - interested only in grabbing power and in cowing members of the largely Pashtun Taliban movement that forced him to flee Kabul as president in 1996.

"Rabbani is dead, this is one problem solved," said Sayed, a 28-year-old taxi driver in Kabul. "He was a very bad man, and he destroyed this country."

Rabbani may not have been the best candidate to lead negotiations with the Taliban, who rose to power on the back of the violent chaos that plagued his presidency, and whose fighters are now waging a fierce anti-government insurgency here.

But his position as High Peace Council chief gained tacit support for peace talks from otherwise virulently anti-Taliban commanders in his traditional Tajik base in the country's north.

"Rabbani's appointment as chairman of the peace council kept the Tajik groups, the Northern Alliance in particular, quiet in their opposition to talks with the Taliban," Moen Marstial, a member of parliament from the northern Kunduz province, said. "Rabbani was the guarantee that their interests would be secured. They could not refuse the peace talks then."

Rabbani first entered Afghan politics as a Muslim activist in the 1960s, after which he helped lead the Islamist resistance against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s.

He had been a central figure in Afghanistan ever since, using his Jamiat Islami (Islamic Organisation) party to form the crux of the largely Tajik Northern Alliance that ousted the Taliban with US assistance in 2001.

It is the perceived loss among ethnic Tajiks of a stalwart ally on the High Peace Council, however ineffectual, that could prove to be the most potent destabilising force after Rabbani's death, analysts here say.

Because Tajik officials and Northern Alliance commanders were long sceptical of attempts to make peace with the Taliban, Rabbani's death could stir feelings of resentment in the north and harden constituents against future talks.

"Now, the Northern Alliance can say: 'We kept quiet and we wanted peace. And the Taliban and armed opposition - they didn't want peace. So now, we don't want peace with the Taliban," Mr Marstial said.

Indeed, in the immediate aftermath of the attack, the former Northern Alliance commander and Tajik governor of northern Balkh province, Atta Mohammed Noor, told a local television channel that the government "could not have peace with the Taliban".

In the past six months, there have been at least five assassinations of senior government officials, some by Taliban insurgents, including the half brother of Hamid Karzai, the Afghan president.

The worry is that Rabbani's death will push Northern Alliance militias to re-arm, laying the foundation for yet another civil war when foreign troops pull out of Afghanistan in 2014.

"Many key northern leaders were already vocally sceptical of Rabbani's nominal pro-negotiation stance," said one Western political analyst based in Kabul. "If the Karzai government continues to pursue talks, we can expect an angrier, more alienated and possibly re-armed north."