MEERWADA, MADHYA PRADESH // Life in the remote village of Meerwada used to grind to a standstill as darkness descended. Workers downed tools, kids strained to see their schoolbooks under the faint glow of aged kerosene lamps and adults struggled to carry out the most basic of household chores.

The arrival of solar power last year has changed all that. On a humid evening, fans whirr, children sit cross-legged to study their Hindi and mother-of-seven Sunderbai is delighted people can actually see what they are eating and drinking.

"When it was dark, we used to drink water with insects in, but now we can see insects, so we filter it and then drink," said Sunderbai, 30.

Meerwada struck lucky when US solar firm SunEdison picked it to test out business models and covered the hefty initial expense of installing high-tech solar panels in the heart of the village.

But rapidly falling costs and improved access to financing for would-be customers could encourage the spread of such systems down the line, while simpler solar schemes are already making profits in areas where the grid either does not extend or provides only patchy power.

And Asia's third-largest economy, where just this week hundreds of millions were left without electricity in one of the world's worst blackouts, needs all the help it can get in easing the strain on its overburdened power infrastructure.

The country's ministry of new and renewable energy hopes solar systems that bypass the national grid will account for just under one per cent of total installed capacity by 2022. Still a mere flicker, but that 4,000-megawatt (MW) goal would be way up from 80 MW now when so-called off-grid solar systems are still out of reach for most of the country's rural poor.

Large-scale solar facilities that directly feed the grid, such as those at an more than 600 MW solar park recently launched with great fanfare in Gujarat, have been gaining traction for some time.

But potential growth in off-grid solar power offers hope to the 40 per cent of India's 1.2 billion population that the renewable power ministry estimates lack access to energy.

Covering initial investment on solar is crucial as, in a country with around 300 days of sunshine a year, subsequent costs are largely limited to maintenance and repairs.

"The high upfront capital cost is one of the adoption barriers [for solar projects]," said Krister Aanesen, an associate principal at McKinsey & Company's renewable energy division.

Small-scale direct current (DC) systems from Karnataka in the south to Assam in the north-east have already cleared that hurdle, supplying simple lights and mobile phone chargers at 100-200 rupees (Dh6.59-Dh13) per month per light - prices that typically allow installers to cover their initial costs in time.

Mera Gao Power, a private company, fits rooftop solar panels and then transmission to other houses who pay about 40 rupees to connect, with costs thereafter about 25 rupees per week, said Nikhil Jaisinghani, one of the firm's founders. That means it should take about 12 months to repay panel installation expenses of about US$2,500 (Dh9,175) for 100 houses, though the cost is set to fall.

Initial expenses are far more onerous on more comprehensive mini-grids like the one in Meerwada, which includes a room full of batteries that can store enough electricity to provide round-the-clock supply to the village and which has recently started powering water pumps. That mini-grid cost between $100,000-$125,000 to build, California-based SunEdison estimated, but the cost of such grids is expected to fall, said Ahmad Chatila, president and chief executive of MEMC Electronic, SunEdison's parent company.

In the meantime, the government is offering 30 per cent of the project cost and in some cases low-interest loans for solar power systems.

Still, systems are beyond the reach of many poor, rural customers, so some solar companies are putting up the 20 per cent deposits on loans required by banks or acting as guarantors for customers who are outside the conventional banking system.

The villagers in Meerwada have added an unexpected ingredient to the cost equation - frugality. Lights even now are turned on only when darkness falls and fans target the youngest children and the elderly, saving on power use.

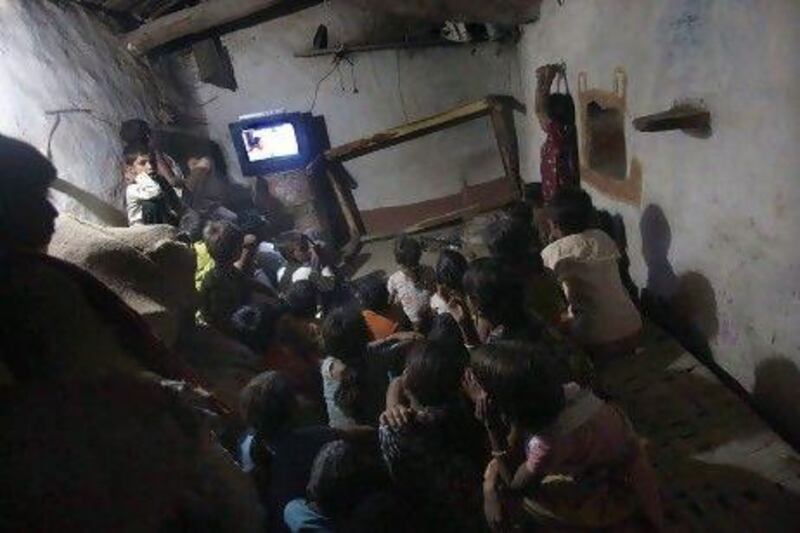

Only the village leader, Sampat Bai, has been able to afford a television but it's open to all and her bare-walled main room is crowded when the latest epic dramas come on screen and the children have finished their homework.