BENGHAZI // Amid all the well-meant official talk about lofty ideals of justice and not repeating the sins of the brutal Qaddafi regime, Atif El Hasia injects a sober note.

"If we have the opportunity to capture one of the top members of the regime, are we prepared to rise above all this and bring them to justice? I can do it, but I didn't see my brother killed. I didn't see somebody raped in front of my eyes," says Mr El Hasia, a physician who joined the uprising in February.

As insurgent forces prepare to lay siege to Sirte, the home town of the former "brother leader", discussion has begun turning to the challenge of administering justice in a deeply wounded and scarred - and deeply angry - society.

Already, evidence has emerged of mass killings of prisoners by the Qaddafi regime and extrajudicial shootings of prisoners by opposition forces, according to Amnesty International.

With the arrival of the Eid Al Fitr, emotions are running especially high. Hundreds of Libyans newly released from Col Qaddafi's prisons are arriving by plane and ship back to their home towns, their bodies and minds disfigured by the torture and mistreatment they suffered at the hands of the regime's jailers. As they mark Eid with their reunited families around the dinner table, they will recount what happened to them.

But the sheer enormity of what Libyans have suffered under the 42-year rule of Col Qaddafi will start to be grasped only when it dawns on them that some chairs around the Eid table will never be filled and that many of the estimated tens of thousands who filled the regime's jails or fought against him will never be accounted for, let alone return.

Which, then, will prevail - the thirst for justice or the hunger for revenge?

Mohammed Ibrahim Noba knows that high-minded invocations of "justice" may not mean much for people such as him in the new Libya.

That is why he is so eager to tell his story, so eager to explain himself, that he cannot talk fast enough. Lips quivering, he pauses between words to gulp more air, then speeds ahead.

Mr bin Noba, 44, is accused of being a member of a secret "fifth column" of Qaddafi loyalists who tried to sabotage the anti-regime uprising in Libya's cities. He is worried that a revised version of "revolutionary justice" - Col Qaddafi's version of summary execution - might be imposed on him.

Sitting on a bare mattress at a temporary prison on the outskirts of Benghazi, he says he was merely an accountant for the state security apparatus in Tripoli. Nevertheless, he has trouble explaining why he came to Benghazi - he knows only one person in town. He insists, however, that he has been against Col Qaddafi all along.

"By God, I should not be here," he says, raising his hands in the air. "We all just want to go home. I believe in the revolution. But the others in here … I'm not so sure."

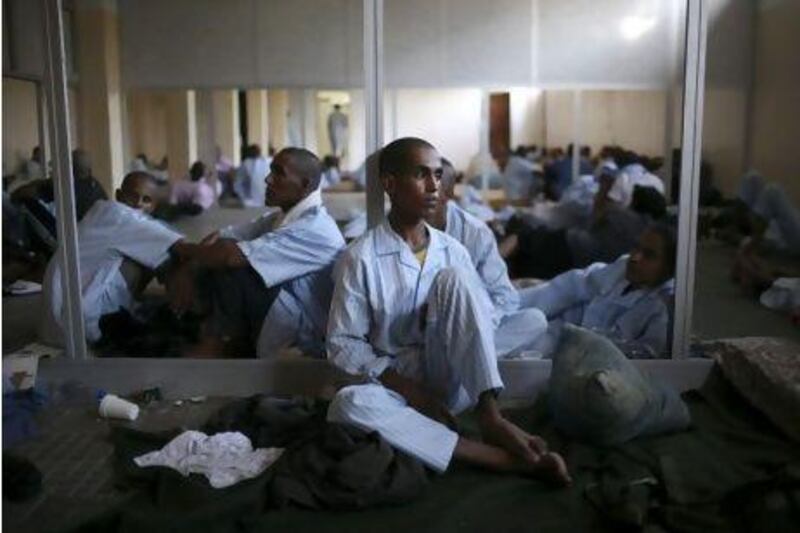

Mr bin Noba is being held in this jail, a former youth correctional facility, with about 90 other inmates, mostly soldiers in Col Qaddafi's army. When they are not inside one of the several large cells stretched across one of the many thin mattresses strewn across the floor, they lounge in a single poorly lit hallway, overseen by guards in mismatching uniforms.

Yousef al Aseifer, the military prosecutor for the forces of the new interim government, estimates that by last week insurgents had captured more than 2,000 of Col Qaddafi's forces across the country. That tally is increasing by the hundreds each day. Most are Libyan, but there were also recruits from Mozambique, Niger, Chad, and Ghana.

Mr Al Aseifer understands that many of those imprisoned were misled. During questioning they say the regime ordered them and thousands of young men like them to defend the country, and claimed it was under attack by foreign mercenaries and Al Qaeda operatives who had taken control of Benghazi.

"Some of them even thought they were coming to guard a football match in Brega," he says.

Criminal charges have not yet been brought against any prisoner because the country is not yet stable enough to restart the judicial system, Mr Al Aseifer says. He promises that justice will be speedy and impartial. He also sets a high - perhaps impossibly high - standard for impartiality.

"The most important thing is to have justice served against those that betrayed us," he says. "This is one of the steps to heal the country."

This could mean that many prisoners could be released for lack of evidence, a move he concedes will be hard for families who have been victimised by Qaddafi's regime.

Ghanei, 25, a soft-spoken army reservist from Sabha, believes the scales of justice in the new Libya will not be skewed.

He was working as a cook when his Qaddafi army convoy was ordered to surrender at an opposition checkpoint. He tried to escape but was shot through both legs at close range, and the bullets severed a nerve.

As he lay bleeding on the ground in the dark, Ghanei drew a circle around himself in the sand and prayed to God to protect him. An opposition commander took pity on him and took him to hospital, where he was saved by doctors, then arrested.

"To be honest, I don't really care who is in charge, as long as the country is safe and stable," he says. He is confident that the rebels will treat him fairly because they are compatriots.

"Our commanders told us they were all foreigners, terrorists," he said. "When I got to Benghazi, I saw that they were all Libyans. It was a shock."

* * * * *

In the studios of a radio station here in Benghazi, Dr El Hazia, now as an official in the interim government's media department, is one of four presenters fielding calls from Libyans excited to offer their views on how justice should proceed in the post-Qaddafi era, advocating everything from hangings to trials in the International Criminal Court.

The debate crystallises around the fate of Col Qaddafi himself. "Regardless of whether we all believe in capital punishment or not, I think it will give a lot of closure to a lot of Libyans if he is executed," said Lujane Benamer, an Irish-Libyan law student.

"Personally, I don't agree with capital punishment, but I'd like to see it with Qaddafi and his family."

Alaa El Huni, a member of the National Transitional Council, interjects. "That is a paradoxical statement," he says. "If you want to be true to your statement, then Qaddafi should be treated like any other Libyan citizen."

For good or ill, history should be a guide, Mr El Hasia says: "See how Mussolini was killed in Italy. See how Ceausescu was executed with his wife in Romania. That's the scene to consider."