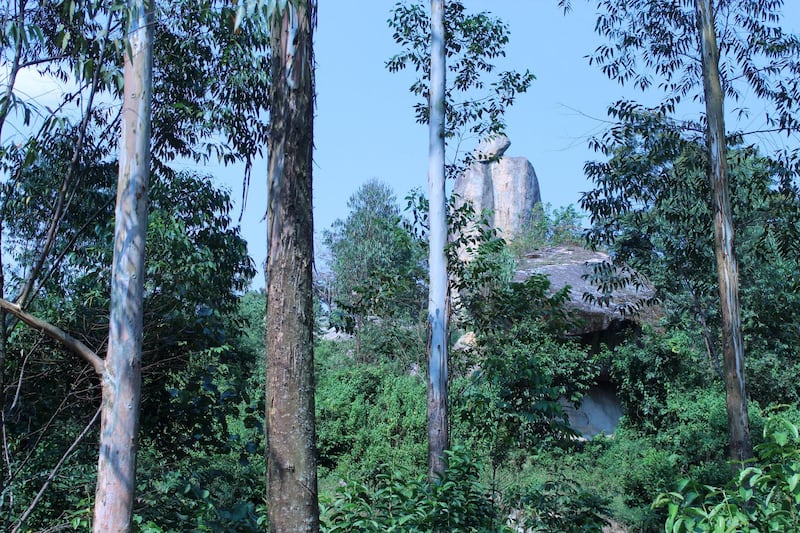

Deep in western Kenya, three kilometres outside Kakamega town on a ridge that overlooks the Kisumu-Kakamega highway, stands The Crying Stone of Ilesi.

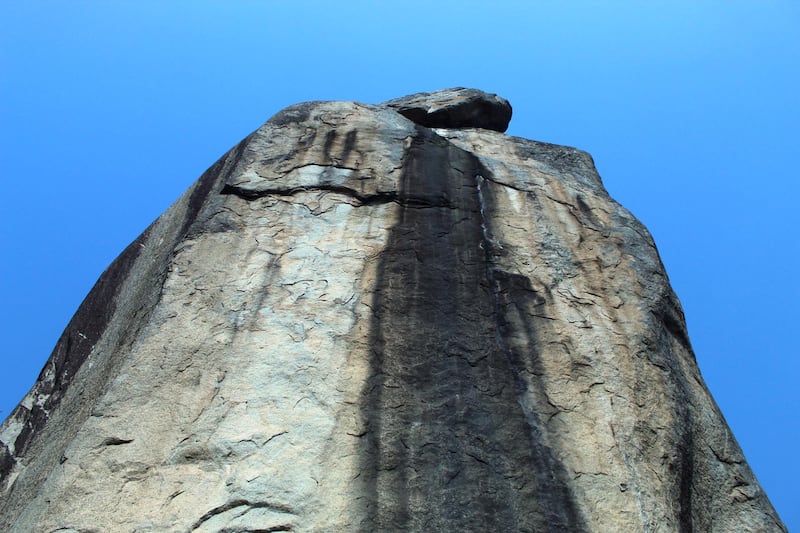

Known in the local tongue as Ikhongo Murwi, it is about forty metres tall – a large boulder balanced on a column of rock with water flowing from a groove in the centre.

The strange rock formation resembles a solemn head resting on weary shoulders and, from certain angles, it looks like a person who is crying.

However, in recent years, the tracks made by water running down the rock face have been more visible because the Crying Stone of Ilesi is often dry. It hasn’t cried continually – as it once did – for years, and the exact cause is unclear.

Some point to agroforestry activities in Ilesi, where eucalyptus trees – called money trees because they are sold for use as electricity poles – have been planted en masse, sucking up large amounts of groundwater.

Others blame the effect climate change has had on precipitation levels, something that has led to water sources below and above ground being tapped much faster than usual.

A climate risk profile on Kakamega County published by Kenya's Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries reveals that while there has been an increase in the average annual rainfall in the county in recent years, it has been erratic and largely concentrated in highly intense bursts.

“Farmers noted changing seasonality, including delayed onset of rains, for instance from March to April; unreliability and variability of the rains; reduced or increased amounts of rainfall; higher temperatures during the hot season; and much lower temperatures in the cold season," the report said.

"Farmers attested to receiving more erratic rainfall, including unusual early rains followed by weeks of dry periods."

Still, the science linking dropping precipitation rates to the drying up of the stone's water is unclear.

Samuel Ayieko, a Water Resources Management Authority official in Kakamega, said when water flowed down the stone, "it meant that it was going to rain".

Much about the stone has a mythical quality. “Water is supposed to drip down; the unique thing about the stone is that the water comes from the top, so it can’t be a spring.”

In the lobby of the plush Golf Hotel in the heart of Kakamega town, a painting of Ikhongo Murwi is prominently placed. Kakamega is replete with symbols of the stone, from the numerous hotels in Ilesi named after it, to the county flag with the stone at its centre.

It also features prominently in local lore. Among the Isukha community that lives nearby, it is believed the stone's "tears" are a harbinger of a bumper harvest, while in pre-colonial times, before the British expanded their influence in Kenya, the rock acted as a good omen for local Isukha warriors.

One account says Nandi warriors, believing the rock was a source of strength for Isukha fighters, tried to pull it down but failed. By the end of the day, more than 100 Nandis had died in battle.

But with climate change wreaking havoc on local water resources, the stories that have sustained local culture across the generations are coming under threat.

Gerishom Majanja, a local activist and an Isukha community leader, remembers happier times for the crying stone.

In his childhood, the area was perpetually wet and the stone rarely ran dry. Ilesi used to be swampy, and teemed with bird and animal life.

When it rained, water would trickle down the sides, leaving dirty streaks that remain visible, even in times of drought.

“If it reaches a point when the stone is permanently dry, then a new narrative will develop,” Mr Gerishom said.

Alternative stories are already being spun. In a public address made two years ago, Wycliffe Oparanya, the governor of Kakamega County, declared that the stone had run dry because he had ordered it to but said "if you visit, it will cry after five minutes".

Other groups of people are making efforts to reclaim the narrative. Mr Gerishom’s clan, the Bamilonje, whose patriarch was an early settler in Ilesi, is forming an association to protect the stone’s heritage.

Their plan is to establish a museum that tells the history of their clan and its relationship with the stone.

Despite the stone's water drying up, they are determined to preserve its touristic appeal.

“We want to keep the myth so that you guys can keep coming,” Mr Gerishom said.

The area is rich in attractions, from the Kakamega Forest Reserve for birdwatching and hiking to the Nabongo Cultural Centre that chronicles the history of the Abawanga tribe.

However, it is the Crying Stone of Ilesi that serves as a proud symbol of the town.

There are no figures on the number of visitors the stone attracts every year but it features prominently in tour packages featuring the region's top attractions.

TJ, a travel operator in nearby Kisumu, keeps the stone in tour itineraries, despite the lack of water. “The history still exists,” he says.

In recent decades, the stone has recovered its status as a site for religious pilgrimage, with members of the Catholic and Legio Maria churches among the most frequent visitors.

Whereas in the past, these churches discouraged any association with carry-overs from the old religion, now their congregants venture to the shrine in prayer.

The steady stream of visitors provides a revenue stream for some members of the local community, whether through tours and entry to the site, as well as the restaurants and hotels the stone helps fill.

Sivincia, an Ilesi local, lives next to Ikhongo Murwi. The worshippers, she said, pray at the stone from six in the morning until 9pm when they retire to her house to sleep, before waking up the next day to repeat the process. She receives a small sum for hosting.

“They leave me something for bread, ” she says.

But the longer the stone stays dry, the higher the chance that the old beliefs may fall away, leaving this local landmark devoid of the stories that have enhanced the town's status for generations.