It makes for shocking viewing: two men on a moped approach a group of children on a street in India, grab one, and speed off with onlookers in pursuit.

The video went viral, alerting everyone to the menace of “child-lifters” prowling the nation’s villages.

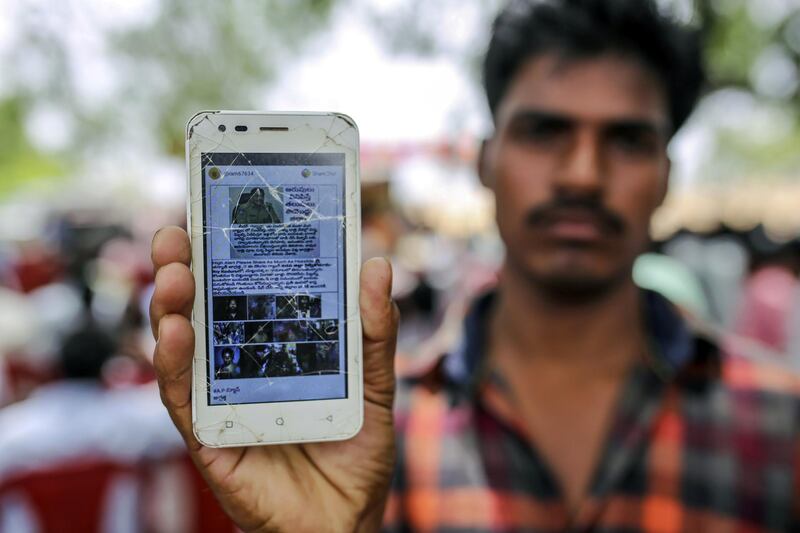

Sightings of more, similar incidents then emerged on social media, with murderous consequences. In recent months, more than 20 people have been lynched.

All of them were innocent, victims of the latest and darkest manifestation of fake news.

The video was actually part of a public safety campaign running in Pakistan, and made clear the scene had been staged. But just the “kidnapping” element began circulating on social media, feeding fears of child molesters stalking every village.

Some experts have blamed the resulting mob murders on the rapid take-up of Whatsapp in rural India.

With no prior exposure to a global social media service, many lack the skills to spot fake news.

This has now led to official campaigns warning users to check information before sharing it.

Yet blaming the naivete of social media users fails to reflect he perniciousness of the fake news phenomenon.

Urging people to check information seem perfectly reasonable until one asks: with whom?

In the child kidnapping case, it wasn’t just gormless users of social media that were spreading fake news. Mainstream regional TV broadcasters have also been accused of repeating the rumours.

WhatsApp’s popularity among networks of friends has also been blamed for helping to spread unverified facts. When a rumour circulates among a group of people we like and trust, it acquires a credibility it would never otherwise enjoy.

The “invitation-only” nature of WhatsApp groups also makes tracing fake news stories back to their origins much more difficult.

The challenge in combating fake news is not its virus-like nature. The challenge is that fake news undermines the standard means of stopping lies: access to the truth.

That makes it more than just a fast-spreading virus. Fake news is the epidemic of the information age, wreaking havoc by attacking the “immune system”of reputable sources.

This pernicious feature of fake news predates the era of social media. One of the most notorious examples has been circulating in the mainstream UK media for nearly 20 years.

In 2000, a consultant paediatrician in Newport, Wales, returned home to find the word “paedo” sprayed on her front door. A police investigation concluded it was probably the work of a stupid teenager who had misunderstood the consultant’s job title.

Yet the story quickly took on a life of its own. Some media reports stated the consultant had been asleep at home when her house was attacked by a mob. Others suggested her home had been broken into and vandalised.

Then the reports became more florid. Some claimed a baying mob – sometimes consisting of furious parents of children - had been involved. Their actions varied from chasing the consultant down the street to burning down her house.

Then the scene of the attack somehow shifted 200km from Wales to Portsmouth, England.

With the usual sources of verification now undermined, other trusted sources began falling prey to the fake news effect.

By 2006, a highly respected BBC editor gave yet more credence to the “mob attack” story by citing it in a public lecture – on, ironically enough, declining standards in journalism.

Just last month, the story popped up again in the comment section of a national newspaper, with readers insisting the story was true because they had been able to verify it online.

Given its ability to subvert even trusted sources, how can the epidemic of fake news be halted?

In testimony to the US Congress earlier this year, Mark Zuckerberg made clear his belief that the answer lies with that miracle du jour, artificial intelligence.

According to the Facebook chief executive, AI is already helping to spot fake news, and will get even better over the coming years.

There is certainly no lack of interest among computer scientists in tackling the problem.

One major strand of research is focusing on identifying fake news through both the claim being made, and how it is expressed.

Much fake news centres on emotive issues like politics and the well-being of ourselves and those we care about. But studies have shown that trustworthy reports tend to longer, contain direct quotes and use more words expressing doubt, insight and quantification, while fake news tends to be brief, more repetitive and conveys more certainty.

So-called neural computers are being created that can “learn” to spot fake news using such characteristics. But their hit-rate is around 70 per cent – far short of that needed to halt the epidemic.

Another approach focuses on the way fake news spreads across social media. Genuine reports are often re-posted directly from the same authoritative source, creating a star-like pattern with the source at its centre.

In contrast, fake news is often spread by people reposting claims made by other people, creating a more meandering, tree-like pattern.

Many experts believe, however, that computers alone will never be up to the task. But including humans assessors also has its drawbacks.

For years, news-sharing sites has allowed users to flag up questionable claims. Yet this often results in users alerting moderators to stories they just disagree with.

Last month, Facebook told The Washington Post that it is now trying to tackle the problem by rating users according to how reliable they are in reporting genuinely fake news.

The best approach probably lies in a combination of both technology and human assessment. But in truth fake news will always be with us, and efforts to deal with it will always be playing catch-up. For as Mark Twain famously put it, "A lie will go round the world while truth is pulling its boots on".

Except he didn’t. It was someone called C H Spurgeon.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Professor of Science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK