As it sat on the launch pad at Kennedy Space Centre on the morning of January 28, 1986, Challenger was already a veteran of space flight.

This would be its 10th mission and the 25th since the inauguration of the Space Shuttle programme in 1981.

So routine were shuttle launches that the American media had largely lost interest in covering them. That this flight of Challenger was covered live by the networks was largely due to the presence of Christa McAuliffe, who would be the first teacher in space.

What happened next is told in a new Netflix documentary, Challenger: The Final Flight.

At one minute and five seconds after launch and an altitude of more than 14,000 metres, mission control issued the command “go at throttle up”, indicating the engines should go to full power.

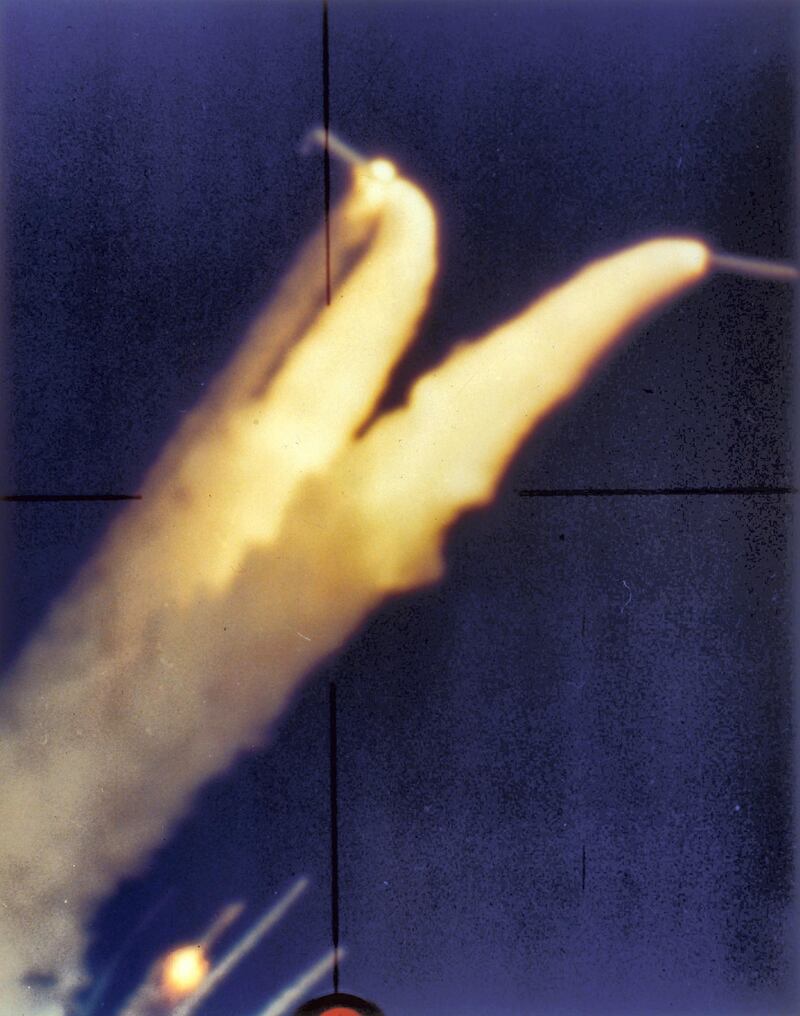

Eight seconds later, Challenger disappeared in a fiery cloud. Spectators on the ground, including McAuliffe's parents and 18 of her pupils, watched in confusion and then horror as the flight path split into two swirling horns of smoke and cascading debris.

"My God, there's been an explosion," the KNBC television commentator, Kent Shocknek, cried out. By then, most of networks had already returned to their regular programming, with the exception of a relative newcomer to broadcasting, CNN, whose anchors were reduced to stunned silence.

The space agency, Nasa, though, had arranged for a live feed to classrooms across America. Hundreds of thousands of traumatised schoolchildren watched live as McAuliffe and her fellow crew members perished in horrific fashion.

As they now enter middle age, the Challenger disaster is imprinted as an early memory on a generation of Americans, as much as the assassination of President Kennedy was for their parents and 9/11 on their children.

The four-part Netflix series does not uncover any scandals or reveal new evidence about the tragedy. Rather, nearly 35 years later, it is a sobering reminder of the vulnerability of large organisations to ignoring warnings and making mistakes that can have catastrophic consequences.

As was later discovered, the Challenger shuttle did not explode that day. Burning gases escaping from one of the two rocket boosters caused the main external fuel tank to break apart and both boosters to detach, creating a fireball.

The shuttle, which had no escape system, continued to ascend for another 25 seconds, then plunged back to Earth as aerodynamic forces ripped it apart. All except for the crew compartment, which remained intact until it hit the Atlantic Ocean at 320 kph nearly three minutes later.

The astronauts probably survived, uninjured, until its impact with the water, but mercifully would have most likely lost consciousness before then.

Their remains were recovered the following March, along with the troubling discovery that three of the four emergency oxygen suit packs on the flight deck had been activated.

The inquiry that followed uncovered the cause of the disaster. Freezing weather in Florida the night before the launch had damaged the elasticated seals known as “O rings” between the sections of the rocket boosters allowing them to leak.

As the Shuttle reached full power, pressurised burning gas shot from the side of the right booster, causing it to break away, and damaging the main fuel tank to the point of destruction. The Shuttle was now doomed.

The inquiry, and the media investigations that accompanied it, also did something else; puncturing the myth of Nasa and American exceptionalism in space that followed the Apollo Moon landings the previous decade.

It exposed a culture of arrogance in the organisation, in which smaller voices of dissent struggled to be heard, including those who had long warned that the Shuttle was potentially unsafe.

It was also a stark reminder of the dangers of space travel. With the Shuttle programme, and the reusable winged craft that landed like an airplane, Nasa had promoted the image of almost mundanity in its operations.

As the Netflix series recalls, the doomed flight was informally named “the teacher’s mission” and “the first flight of a private citizen”. It showed space travel was now for “ordinary people”, and ended the “old mystique of the astronaut tradition”.

Footage of the appalled faces of children watching the destruction of Challenger, some still wearing party hats and clutching celebratory balloons, shows how premature that vision was.

As well as McAuliffe, the six others who died included Ronald McNair, only the second African-American in space, Judith Resnik, the first Jewish astronaut, and Ellison Onizuka, a Buddhist and the first Asian-American astronaut. It was a part of the American dream that also perished that day.

All Shuttle missions were paused for nearly three years for a major redesign. In 2003 the Space Shuttle Columbia broke apart on re-entry, the result of damage to a wing caused by insulating foam breaking from the main fuel tank on launch. Again, all seven crew were killed.

Despite its obvious flaws, the Shuttle programme continued until July 2011 until it was finally withdrawn. America only returned to manned space flight this year, using a more sophisticate version of the capsules that launched manned flight six decades ago.

In total, 19 men and women have died during space flight, 14 of them on the Space Shuttle. Four Russian cosmonauts have perished, including the three crew of Soyuz-11, whose capsule depressurised in space in 1971. About a dozen more have died in training accidents, and perhaps hundreds of ground workers in launch pad explosions, mostly in the former Soviet Union.

Their sacrifices are a reminder that space travel comes with a human price. It underlines the bravery of astronauts but has not deterred those who continue the journey.

It is also worth noting that the 3.4 per cent death rate for astronauts is the same as calculated by the World Health Organisation in March for those infected with Covid-19.

On the evening of January 28, 1986, the then US President Ronald Reagan went on television with a special word for the country’s children.

"The future doesn't belong to the fainthearted; it belongs to the brave", he told them. "The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we'll continue to follow them."