For decades, Brooklyn's Arab-Americans have come together at Widdi Hall, a worn-at-the-edges catering facility in the Sunset Park neighbourhood that often plays host to the community's enormous wedding celebrations. Last Thursday, the hall was packed with hundreds of Arab Brooklynites who had gathered to play their roles in a different kind of ritual: the Great American Panderfest. The occasion was a Meet-the-Candidates night organised by the Arab American Institute (AAI) as part of a nationwide voter-mobilisation effort it calls "Yalla Vote". Politicians had come to tell the Arab-American community that they too came from immigrant backgrounds. That they too cared about traditional values. That they too wanted to create opportunities for small-business owners.

Several candidates congratulated themselves on reaching out to the Arab-American community - "given the world we live in," as one put it - and expressed their appreciation for their hosts' efforts to make them feel at home. After a young woman wearing a red hijab performed a quavering, tender rendition of the Star-Spangled Banner, Joe Cammarata, a Republican running for State Assembly, told the audience: "When I saw the…what's it called? Habib? Hajib? You know, the dress! When I saw that? With the anthem? I was touched."

Presiding over the evening was Dr James Zogby, the founder and president of AAI. Zogby was beaming as he rose from the table at the front of the room that he shared with the candidates and various community bigwigs to address the crowd. "People say Arab-Americans aren't organised - we are!" he assured the crowd. Zogby has been a central figure in Arab-American politics for more than three decades - and given the glacial progress he's witnessed, his unshakable optimism is surprising. "I've been coming to Widdi Hall, doing stuff in New York for 25 years," he reflected the following day. The past few years - especially following September 11 - had been difficult, he explained. But that was then. Now, he said, "I came out thinking - we're back!"

But the evening's most striking moment was a less encouraging one. During his pitch, Bob Straniere, a Republican congressional candidate, made a rather cursory mention of his support for John McCain. A young man sporting ultra-hip jeans and heavily gelled hair raised his hand, and aired his distaste for McCain's recent statements at a campaign rally in Minnesota. When a supporter there told McCain, "I can't trust Obama. I have read about him and he's not, he's not... he's an Arab," the candidate took back the microphone and said ""No, ma'am. He's a decent family-man citizen."

"Why," the young questioner asked Straniere, "would you support a person who would respond in such an unfavourable way to the community?" A sustained round of applause swallowed the young man's final words, and all eyes turned to Straniere, waiting to see if he would affirm that he believed Arabs could be decent family men. "You know, we all work very hard, we campaign very hard, and sometimes, your mouth goes faster than your brain," he said through a stiff smile. Besides, Straniere declared, McCain hadn't been his first choice - "Rudy Giuliani was!"

This did not quite suffice, and the crowd let Straniere know it with a chorus of boos. The young man sat down, frowning and rolling his eyes. A woman sitting nearby muttered, "They don't get it."

In the end, what was most remarkable about the Brooklyn event was that it happened at all. Politicians like Straniere may not "get" the Arab-American community, but he may have demonstrated the painful conventional wisdom of political professionals - that the rewards of outreach to Arab and Muslim Americans are too slight to justify the risk at a moment when some people regard the idea that a candidate is "an Arab" as a damning indictment. "Both Muslims and Arab-Americans have been ill-treated in this political environment," noted Steve Clemons, a veteran observer of American politics and popular blogger who is a senior fellow at the New America Foundation, a Washington think-tank. "There has been some tacit acceptance of that, even by people around Barack Obama," he added. It is hard to overstate the marginalisation of Muslims and Arab-Americans in American politics. They are seen as politically radioactive - and worse, this status quo seems to be widely accepted.

The woman who told McCain that she couldn't trust Obama was the prototypical target of a months-long campaign by ultraconservative and neo-nativist groups that have captured a significant section of the Republican party and infected McCain's campaign - with the candidate's apparent consent. "Vote McCain, not Hussein!" is their chant of choice. "The media just lets this go and tolerates it," said Edward Ayoob, a Lebanese-American lawyer and lobbyist. "Imagine if that woman had said, 'I can't trust Obama because he's black,' and McCain had replied, 'No, he's not black, he's a decent family man.'"

But as the former Secretary of State Colin Powell pointed out on Meet the Press two weeks ago, insinuating that your opponent is a Muslim has become a permissible campaign tactic. Powell observed that Obama is in fact a Christian - but he may have been the only prominent figure in recent months to stand up and protest the underlying logic: "But the really right answer is, What if he is? Is there something wrong with being a Muslim in this country?"

Mobilising a community to participate in a political system whose candidates reflexively run in the other direction is an unenviable task. But pervasive anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiment alone cannot account for the striking disengagement from politics that has characterised successive generations of Arab-Americans. After all, politicians frequently ally themselves with interest groups that do not enjoy widespread public support or visibility.

But for decades Arab-Americans have been collectively unable to transform themselves from an ethnic group to an interest group - the main problem being that they are not really a group, and it's not entirely clear what their interests are. Rather, they are a demographic divided: by national origin, by religion, by ideology. These divisions - along with a shared cynicism about politics rooted in the experience of repression and despotism in the Middle East - have complicated Arab-American solidarity, and prevented people from participating in American politics as Arab-Americans.

Reliable estimates of the number of Americans of Arab descent are hard to come by. The Census Bureau estimates around 1.2 million Arab-Americans, but most demographers argue this is a severe undercount; the true figure is probably closer to three million. All agree, however, that the community is heavily concentrated in a relatively small number of major population centres: one out of every three Arab-Americans lives in California, New York or Michigan.

Immigrants have come to the US from all 22 Arab states, mostly in three major waves, beginning in the 1870s and continuing to the present day. It's a remarkably diverse community, and one that resists easy generalisations. Close to two-thirds of Arab-Americans are Christians; about one quarter are Muslims; and the rest a typically North American hodgepodge of other faiths or avowed secularists. As a whole the community has achieved considerable socioeconomic success: more than 40 per cent of Arab-Americans have a bachelor's degree, and more than 15 per cent hold postgraduate degrees, well above the national average. Arab-American households have an average annual income that is 8 per cent higher than the national average, and almost 20 per cent of Arab-American households have an annual income over $100,000.

But these achievements have not translated into political clout. The success of Jewish-American advocacy organisations and the pro-Israel lobby (whose influence is real but frequently overstated) has invariably led to questions about the absence of an Arab counterpart. But this puts the cart before the horse: for now, at least, there is no Arab-American body politic. Michael Suleiman, a political scientist at Kansas State University, has studied and written extensively about Arab-American politics for over twenty years. "Arabs, including Arab-Americans, like to think there is something called the 'Arab world', when in fact there are many Arab worlds," he noted. "They assume there should be unity when there isn't."

Arab-Americans are divided not just by national origin and religion, but by a corrosive form of "exile politics" that recreates old schisms in a new country. "When there are conflicts that pit Arabs against Arabs, you see it imported into the US," said Hussein Ibish, the executive director of the Foundation for Arab-American Leadership. "Palestinian-Americans are angry with each other. Lebanese-Americans continue to sneer at each other. And you still have village and party affiliations, subnational divisions that play themselves out."

These kinds of divisions have made it almost impossible for Arab-Americans to reach consensus on many issues - even the one most Americans probably expect them to agree about: the Arab-Israeli conflict. The pro-Israel lobby has been successful in part because groups like the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) have managed to create a powerful image of solidarity when it comes to uncritical support of Israel. The unity is illusory - Jewish-Americans have many disagreements over Israeli policies. But the pressure on Jewish-Americans to present a unified front is no longer overwhelming, since the US-Israel alliance has only grown stronger over the past 40 years. Arab-Americans, by contrast, operate from a position of acute weakness.

The Arab-Israeli conflict is hardly the only focus of politically engaged Arab-Americans, but the rifts over this emotionally charged issue provide a key - a "road map", if you will - to a more fundamental divide. A larger, more "mainstream" group argues that Arab-Americans should engage with American politics to influence the course of the "peace process". This camp, which supports a two-state solution and seems more willing to compromise on the right of return for Palestinian refugees, represents a more establishment-orientated sector of the community, represented by organisations like AAI and the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC).

A smaller - but significant, vocal and growing - minority rejects the idea that Washington will ever be an "honest broker" between Israelis and Palestinians, and points to the abject failure of 15 years of negotiations. Among this faction are second- and third-generation activists, students and professionals in their twenties and thirties, alongside an older, educated cadre of first and second-generation Arab-Americans who reject that hyphenated identity and remain loyal to the vision (and rhetoric) of the post-1967 national liberation struggles. It includes many who champion the idea of a single, democratic and secular state that would be a homeland for both Jews and Palestinians.

This stark divide over the most basic questions of engagement in the political process - which to some degree masks a conflict over identity - presents a major obstacle to mobilisation. "We're trying to build a politically astute, organised community," said Rebecca Abou-Chedid, the former director of government relations for AAI. "But the community is not sure where it wants to head. We don't have a community that is dying for us to do just one thing."

In effect, while Arab-Americans have assimilated into the social, economic, and cultural fabric of America, they have not undergone what might be termed political assimilation. "We carry with us a cynicism about politics," argued Hussein Ibish, "because the terrain of the political in the Arab world in the past one hundred years or so has been one, with few exceptions, of defeat and failure." Said one Arab-American academic who did not want to be quoted by name: "If these are people who are still first-generation, and their experience is the secret police putting electrodes on their testicles, I don't think they're going to trust the cops, I don't think they're going to vote, I don't think they are going to know anything about the constitution. Even if they have $300,000 in income! They're not going to contribute to political campaigns and they're not going to go to PTA meetings with other Americans and argue with them in flawless English."

"We shouldn't kid ourselves," warned Khalil Marrar, a professor of political science at DePaul University and the author of a recently-published book titled The Arab Lobby and US Foreign Policy. "There's no 'Arab lobby' in the same sense that there's an Israel lobby. To say that there is would be insane." There have, however, been numerous attempts to build such a force, dating from the founding in 1967 of the Association of Arab-American University Graduates, which tried to forge a progressive, secular Arab-American identity that would connect the struggles of Arab-Americans to those of oppressed people everywhere. As Gregory Orfalea writes in his history, The Arab Americans, AAUG "saw itself as a kind of intellectual laboratory for change in the Arab world." The group held conferences and published the influential Arab Studies Quarterly, which was co-edited by Edward Said. Their impact may have been marginal, but it was visible enough to merit the attention of the Nixon administration, which targeted the group for surveillance and wiretaps.

But AAUG was riven by ideological factions and bitter infighting - "Arab League syndrome," in the words of Jamil Jreisat, who served as president of AAUG's board of directors in the early 1990s - "narrow, parochial, and distrustful behaviour peddled as representation of diverse interests," as Jreisat wrote in a short history of the group. By the end of that decade, the toll of this dysfunction had become insurmountable, and AAUG folded in 2000.

Another group, the National Association of Arab Americans, was founded in 1972 to push against America's then-recent shift towards Israel, and was the first Arab-American organisation to employ full-time registered congressional lobbyists. Khalil Jahshan, who served as the group's director during the 1980s and 1990s, has said that the group's mission was "to counter the effects of AIPAC on US politics." Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the group provided a voice on the Hill and in the press for the "Arab side" in the unending series of Cold War-flavoured imbroglios that defined that period. But it was tiny, had a very small budget, and was buffeted by growing anti-Arab sentiment after the oil embargo. Over the next three decades, the group saw the scope of its efforts diminish as funding dried up, and it merged in 2000 with ADC, which looked as though it might carry on the quest to create a lobby.

ADC was founded in 1980 by James Abourezk, the first Arab-American to become a senator. (After serving one term, he opted not to run for reelection, concluding that the Senate was a "chickens**t outfit".) The theory behind ADC was that the chief impediment to Arab-American political influence was the negative images of Arabs encouraged by stereotyping in the media and Hollywood. ADC attempted to foster a more positive view, and its mission quickly extended to assisting Arab-Americans with discrimination lawsuits and lobbying Congress on civil-rights issues.

ADC is the longest-surviving of the mainstream groups: at its height, during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, it boasted 22,000 members. But its membership has waxed and waned with events in the Middle East. By 2002, Orfalea estimates, that number had shrunk to 5,000. It is currently the only organisation that employs a registered lobbyist to work the halls of Capitol Hill on behalf of Arab-Americans, but its small budget - about $2 million a year - makes this difficult. After all, to have any hope of persuading elected officials to take certain positions, lobbyists have to be able to deliver votes or money. Of course, a combination of the two is preferable. But the Arab-American community can't offer much of either.

In Congress, the "Arab-American lobby" is one person: Christine Gleichert, ADC's legislative director. But ADC's disclosure forms indicate that they spent only $80,000 on lobbying activities last year - a paltry sum. (AIPAC, by comparison, spent almost $2 million just on lobbying Congress, roughly equivalent to the entire ADC budget.) And the lobbying Gleichert does undertake is more focused on domestic civil-rights issues than on foreign-policy.

ADC's director of communications, Laila al Qatami, was candid about the results: "I would be hard pressed to say the lobbying we do on foreign policy has been all that successful. It really hasn't."

A veteran of AAUG and ADC, where he served as executive director until a bitter falling-out with Abourezk, James Zogby has become the American political establishment's "go-to-guy" on all things Arab-American. The Arab American Institute, which he formed in 1985, is an idiosyncratic organisation that does advocacy on the Hill and in the executive branch, but does not employ a registered lobbyist. It conducts research and publishes studies on Arab-American demographics and opinions, but it's not quite a think-tank. Its bread and butter, ultimately, is Zogby's quest to mobilise the Arab-American community through grassroots organising.

But sustainable grassroots mobilisation - even with the help of new technologies that have powered well-financed campaigns like that of Barack Obama - is still a very tall order for smaller outfits like AAI, whose relatively small budget (around $2 million a year) limits the scope of its efforts. The AAI headquarters on K Street - the traditional Washington locus of lobbying clout - have a down-market feel that reflects this fiscal austerity. But it is blessed with a core staff of committed, impressively-credentialed Arab-American women in their twenties and thirties.

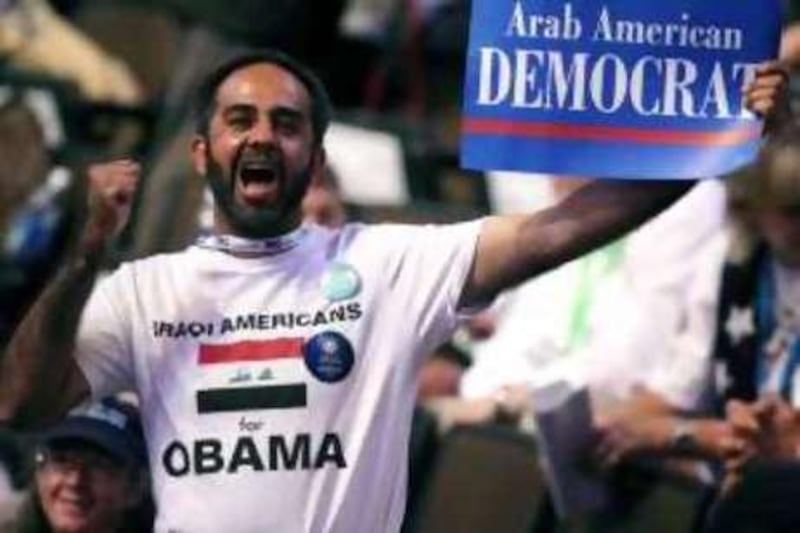

When I visited earlier this month, all energy was focused on the Yalla Vote project - whose real goal is not merely to get Arab-Americans to the polls, but to get them there voting as Arab-Americans. The group has hired regional field organisers in seven states, set up Meet-the-Candidate nights, and is directing a "virtual phone bank" that allows volunteers to make get-out-the-vote calls. On this particular night, AAI staffers had stayed at the office after hours to make calls themselves. AAI has purchased access to voter-information databases, and uses a software programme to identify "Arab" names. (Perhaps as a result, more than a few calls were placed to South Asian Muslims or African-Americans who likely adopted Arabic names after converting to Islam.)

"I'm calling as a volunteer for the Yalla Vote project, which is working to ensure that Arab-Americans have the resources to participate in this year's crucial election," the staffers would cheerfully inform whoever answered the call. "Can I verify that your family has origins in the Arabic-speaking world?" Of the Arabs reached that night who were willing to share their preference, almost all said they planned to vote for Obama. (One AAI staffer handed me a couple of "Arab-Americans for McCain" bumper stickers that had been stashed in her desk drawer. "You can take some of these," she said with a mordant smile, "since they'll never be used.")

Steve Clemons praised AAI for its mobilisation efforts. "I think Zogby understands the importance of building capacity and structure, registering people, getting people to move forward." But Clemons also noted that AAI remained focused on areas with large Arab populations, without much progress fostering influence nationally. "You've got to have a 50-state strategy and you've got to be building on that and showing that you're generating results and outcomes," he said. "It's kind of like an interest group that's got a script but hasn't gone 'viral' yet."

AAI's approach - which has yet to yield significant Arab-American political donations or the creation of an identifiable voting bloc - also reduces its voice on foreign-policy issues. Even though AAI does employ a director of government relations, Leigh O'Neill, to act as its face on the Hill and within the executive branch, she is not a registered lobbyist. O'Neill, a former aide to John Kerry who is one-quarter Lebanese, brushed aside my questions about the emphasis on domestic issues: "We don't do Arab politics here. We do American politics here. Our role is to make sure that the US plays a constructive, well-informed, positive role. We have a very accessible message. And we are the ones who are invited to the table."

The trouble with this approach, however, is that AAI has plenty of access but little leverage. As a former Congressional staffer who worked extensively on foreign policy told me: "Because AAI has succeeded in making a name for the Arab-American community, members of Congress and the administration look at them when an issue comes up and say, 'Hey, what does AAI think about this?' But when AAI doesn't lobby on it, the perception becomes, 'This must not be that important to the Arab-American community.'"

Zogby is naturally unfazed by the charge that AAI does not spend enough time on foreign policy. He pointed to the results of a recent AAI poll on the priorities of Arab-American voters. "Almost nobody said Palestine or Lebanon," he told me. "They don't see them as solvable right now. They're focused on home: jobs, business, family, education."

Ziad Asali, who left his position as president of ADC to form a new group, the American Task Force on Palestine (ATFP), decided it was time for a different approach. Unlike AAI and ADC, Asali's new outfit would forego grassroots organising in favour of single-issue advocacy. Instead of building constituencies in the Arab-American community, it would attempt to build them in Washington and Ramallah. By positioning themselves as a "mature", reasonable alternative to the other Arab-American groups, ATFP hoped to appeal to American and Palestinian insiders looking for an effective liaison.

By allying with ATFP, Asali argued, both the Bush administration and the Palestinian Authority could avail themselves of a group that might be able to trade on its members' prominence to sell the Arab-American community on a negotiated solution. It's a top-down approach, one in which the larger community is relegated to the role of passive consumer. Asali, a Palestinian-American, spent most of his life as an internal-medicine specialist and endocrinologist, but moved to Washington in 2000 to focus full-time on advocacy. He believes that his medical experience gives him a unique form of insight: "In the privacy of an examining room, everybody is bare, and the soul is naked. So I do know the American people."

ATFP's message has been crafted with an unusual degree of caution, free of any rhetoric that might make its Washington audience uncomfortable. It "advocates the development of a Palestinian state that is democratic, pluralistic, non-militarised and neutral in armed conflicts" and that lives "side by side in peace and security" with Israel. To help him sell this message, Asali brought aboard Ghaith al Omari, a former senior adviser to Mahmoud Abbas; and Hussein Ibish, who left ADC to join Asali. He also brought on as executive director a well-connected Palestinian-American named Rafi Dajani, who had worked for many years at the American Committee on Jerusalem.

Asali's approach represents "a form of realism," Ibish said. Expressing palpable bitterness about the years he spent working for a grassroots organisation, Ibish explained that ATFP is "an effort to actually achieve something in terms of policy, rather than an effort to organise the community, mobilise the community, please the community, pander to or cater to the community, or otherwise serve the community in a way that makes them feel good but doesn't get them anywhere."

Most of ATFP's activities are decidedly behind-the-scenes; aside from a lavish annual gala, the group holds few public events and doesn't publish much in the way of literature or research. In August, though, it signed an Memorandum of Understanding with USAID to help channel charitable donations to the Palestinian territories - philanthropy that has become harder to carry out during the "war on terror," which has put a chill on giving by Arab-Americans fearful of being involved in activities that might later be deemed illicit.

Asali clearly relishes his new-found access to powerful players, and sees himself as a maverick, breaking with the Arab-American establishment. "We were being fought by the establishment in the Arab-American community," he said, "who are not at all happy about us being so accommodating and moderate." Indeed, when I asked James Zogby about ATFP, he was surprisingly dismissive. "I don't know very much about the Task Force," he said. "I'm way too busy running around the country and writing my articles and doing my shows to have a sense of what they do."

The group has carefully constructed its image - as "grown-ups," in Asali's words - but that effort seemed liable to unravel when the group announced last winter that it had dismissed Dajani, its executive director, for allegedly depositing more than $100,000 in donations intended for the group into a personal bank account. "We turned it over to the authorities," Asali told me, and "they are investigating." (The Washington, DC police would not confirm an investigation, and Dajani declined to comment.) But the episode does not appear to have damaged ATFP - perhaps because it had little grassroots support to lose.

To Michael Suleiman, one of the most authoritative observers of Arab-American politics, the emergence of ATFP traces a familiar arc. "Every new generation of Arab-Americans comes on the scene saying, 'We have a new way of dealing with the issue, and we have greater enthusiasm for doing what we're doing,'" he observed. "In good part, they are ignorant of their own history, the history of their own community. This is my great concern."

What seems clear is that the approaches taken by all of the established organisations have failed at least in part because they have not found a way to address divisions within the community over identity and the efficacy of engagement with American politics. "I think the next generation of leadership is going to be far more Web-friendly and realise how to use virtual networks to demonstrate greater political power than you would otherwise have," Clemons predicted. But the challenge for the future is figuring out how to reach younger Arab-Americans before they become jaded about participation in the political process - if it is not already too late.

"The efforts of many groups over many decades that have said 'Trust the system! Get involved!" have had a very limited impact," said Ali Abunimah, a founder of the Electronic Intifada website and a leading voice among those sceptical of engagement with Washington. However, he added, "it doesn't follow that therefore we abandon all efforts to influence opinion or direction in this country. There have to be voices in the country talking about the alternatives and putting them on the agenda."

But will those voices be heard amid the ongoing din of fractious intra-communal sniping? Not long before his death in 2003, Edward Said - a rare unifying figure in the community - wrote that "nothing can be more disheartening than the disputes that corrode Arab expatriate organisations... instead of trying to unite and work together, these communities get torn apart by totally unnecessary ideological and factional struggles."

"It's no good sitting back blaming 'the Arabs,'" Said concluded, "since, after all, we are the Arabs."

Justin Vogt is on the editorial staff of The New Yorker.