The United States made a “huge mistake” by launching a fake immunisation programme in its quest to find Osama bin Laden, an expert seeking to eradicate polio has claimed.

Chris Elias, president of the Global Development Division at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, said the CIA plot had fuelled conspiracy theories about vaccines in Pakistan, one of only two countries which continues to report polio cases.

The Microsoft founder's Seattle-based charity has been helping fund efforts to eradicate the disease entirely, with Dr Elias saying the drive had been “99.9 per cent” successful. However, polio has persisted in a few stubborn areas in Pakistan and Afghanistan. There have been 28 cases so far this year, Dr Elias said, compared to 22 in the whole of last year.

Issues around inaccessibility and security had contributed to the situation, he said. However, unfounded rumours about vaccinations, leading to people refusing to have them, had also played a part and these had been “fuelled” by the emergence of the Bin Laden scheme.

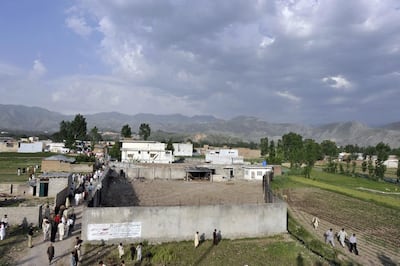

In an attempt to confirm their suspicions that Al Qaeda's leader was living in a compound in Pakistan, the US launched an immunisation scheme with the objective of obtaining DNA from a resident in the property that would confirm any family link.

Asked whether he thought it had been legitimate to use a vaccination programme in that way, Dr Elias said: “No. I think there’s a generally accepted principal that humanitarian operations will not be used as cover for intelligence operations. The United States made a huge mistake in violating that principle in its search for Osama bin Laden – there’s no question.

“But at the same time, there’s some things to clarify. That immunisation campaign was not a polio immunisation campaign [it was hepatitis]. It was a ruse to collect DNA, [but] the DNA was never collected and never used, actually, in identifying the links. In the media, and in some movies, it’s been confused as a polio campaign and hence has fuelled some of these rumours.

“It wasn’t a polio campaign, but it was an immunisation campaign, which was unfortunate. Many groups in the public-health community have spoken out about what has for a long time been the accepted principal of not using humanitarian operations as cover. It’s unfortunate it happened and it’s unfortunate the rumours persist. The reality is children suffer when they don’t get the vaccines.”

Dr Elias said he did not believe the scheme to identify Bin Laden, who was killed by US special forces in a raid on the compound in 2011 despite the failure to obtain DNA, was the “main” reason polio had persisted in a small number of cases.

_______________

Read more:

UAE polio vaccination programme reaches 57 million children in Pakistan

National Editorial: The eradication of polio is finally within our grasp

_______________

It was hoped that polio would be eradicated completely this year, although he said the increase in cases should not be seen as statistically significant, given the low numbers. In 1988, there were more than 300,000 cases, meaning humanity is on course to eliminate only the second ever fatal disease, after smallpox. Other myths about polio vaccinations in Pakistan are that it contains pork fat, forbidden for Muslims, or causes infertility.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has invested about US$4 billion (Dh14.7bn) in Gavi, the vaccines alliance that is holding its midterm review in Abu Dhabi this week, in the past two decades. Polio is one of the diseases that Gavi works to combat. Dr Elias described it as "by far our biggest investment and in many ways our best investment", which shows "Bill and Melinda's understanding of immunisation as one of the 'best buys' in global health".

“For every dollar that we invest in immunisation, we see about $44 return,” he said. “That’s a pretty good return on investment.”

The Gates Foundation – which employs more than 1,500 people, holds more than $50bn in assets and has given out $46bn of grants since it was set up by the Microsoft founder in 2000 – will continue to use its cash to save "the most lives possible at the lowest possible price", Dr Elias said.

As well as immunisation, it is working to improve maternal and child health, to help combat malaria, tuberculosis and HIV, as well as childhood diseases such as pneumonia.

In partnership with the UAE, it is also working to eradicate neglected tropical diseases, which generally only occur in poor countries.

Expanding access to contraception in the developing world is another priority, he said. Asked about religious organisations such as the Catholic Church that have traditionally opposed contraception, Dr Elias said the most important thing is to "listen to women".

“There are 320 million women today in poor countries who are using contraception,” he said. “There is another 210 million women who want to use contraception, but currently don’t have access to the services.

“Many of those women are being advised in different ways by their traditional and religious leaders, and they’re making personal choices to want to time and space their pregnancies.

“Something as simple as spacing pregnancies by three years would cut maternal mortality probably in half and cut child mortality by a third. Most religions do have teachings about commitments to the health of children and families. Providing women and couples the opportunity to space and time their pregnancies is actually part of having a healthy community and a healthy family.”