CANCUN // Top UAE officials joined high-level talks at the UN Climate Change Summit in Mexico yesterday as the 194 nations present heard perhaps the most poignant arguments of all, from the countries with the most to lose from global warming.

The Minister of Environment and Water, Rashid bin Fahad, and Dr Sultan al Jaber, the Special Envoy on Energy and Climate Change, worked yesterday with heads of state and ministers towards a deal on climate that would be acceptable to all by the close of the conference, which wraps up tomorrow.

Countries and alliances have also been making public statements on what needs to be done to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and the UAE is due to address the summit late today or early tomorrow.

Yesterday, the floor opened to African states and island countries in the Pacific, nations that are the most vulnerable to climate change.

Marcus Stephen, the president of Nauru, said that for 14 low-lying Pacific Island states facing large parts of their territory being inundated by rising sea levels, achieving an ambitious climate deal was a matter of urgency.

"There is very little compromise," he said. "When you ask us to compromise, you are asking us to choose how many islands we will lose. This is not a choice we are prepared to make."

Meles Zenawi, the prime minister of Ethiopia, said that while Africa had contributed to less than two per cent of global greenhouse emissions, it was already suffering some of the results of climate change, such as severe droughts.

"We Africans do not have the luxury of debating the cause or nature of climate change, or whether it is happening or not," he said. "The devastating consequences of global warming are with us now."

Poor countries want developed states to extend the Kyoto Protocol, which only outlines commitments until 2012. But the industrialised states have insisted they would only do so if fast-developing countries such as China and India committed to reducing emissions too.

Japan, for one, has declared outright that it would not extend its Kyoto Protocol commitments beyond 2012, a move which has generated widespread criticism from developing countries at the conference.

Despite the stalemate, officials are hoping for some broad agreements to help pave the way for a legally binding deal during next year's round of the negotiations in Durban, South Africa.

Connie Hedegaard, the EU commissioner for climate action, said yesterday that "to come out of Cancun with nothing is simply not an option".

"We know that here in Cancun we cannot get everything done, but it is imperative that we must deliver," she said.

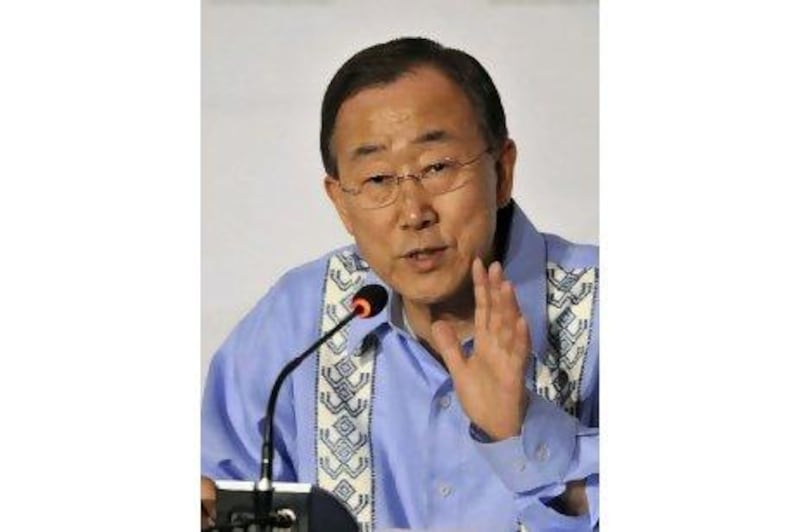

The UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, said that agreements on forest protection, climate adaptation, clean technology and "some elements of finance" were possible.

"Some important decisions are ripe for adoption," he said.

During the Copenhagen climate conference last year, rich countries agreed to set up a US$30 billion (Dh110bn) fund between 2010 and 2012 to help developing countries, and an additional $100bn a year until 2020. But yesterday some delegates complained that the cash had not been forthcoming.

"In Africa the general opinion is that the money is yet to be delivered," Mr Zenawi said.

The Copenhagen Accord mentions these pledges, but is not a legally binding treaty, making the funding uncertain.