In most walks of life, if a boss said to a worker, "Look, you take it easy today. Just pop along for the last few minutes and wrap things up", the employee would jump at the chance.

All the glory, the same fee, but far less effort. And yet in football, players, almost universally, want to play from the start. Everybody wants to be in the opening line-up, to put in the hard yards from the very beginning.

There is a conviction that the substitute is a lesser role, that it almost demeans a player to be on the bench. Certainly, that was how Frank Lampard saw it when he was only brought on after an hour of Chelsea's Club World Cup semi-final against Monterrey, even though that was part of a wider plan to keep him fresh for the final.

To an extent, the disdain for the substitute's role is explained by football's history.

For a long time teams could not make substitutions. Although there was an understanding, in friendly internationals from the late 1940s, that injured players could be replaced, in competition they were only legalised in 1954 and introduced into the English league in 1965.

Initially, teams were permitted to name just one substitute and so, naturally enough, the ideal substitute was a utility player, a Jack of all trades capable of deputising for an injured player in as many different positions as possible.

Even now, with teams allowed to use three of seven substitutes in the Premier League and the Uefa Champions League, a hangover from that attitude remains.

Actually, it takes a special skill to be a substitute.

It is not easy adjusting to a match that has been going on for an hour or more, that has its own dynamic. Some players may take five or 10 minutes to feel their way into a game, playing a few easy passes, calming the nerves and warming the muscles.

A substitute does not have time for that and, besides, everybody else is already warmed up. If they take a few minutes to get into the game it looks far worse than a teammate's tentativeness early in the game.

In the English game, the greatest substitute was almost certainly Ole Gunnar Solskjaer, who could be relied upon to come off the bench and score for Manchester United.

Most famously, he did so to win the Champions League final against Bayern Munich in 1999, stabbing a Teddy Sheringham flick over the line.

That was a goal rooted in instinct; the Norwegian clearly had a natural sense of where he needed to be and an icy cool in taking chances. But he also studied the game assiduously from the bench and that gave him an advantage.

On one occasion he came on as a substitute to score four at Nottingham Forest.

Some benched players give the impression of barely watching matches; Solksjaer studied them, working out where weakness were, where the space might appear, assessing the opposition.

Sir Alex Ferguson, the United manager, called Solskjaer "a student . one of the most intelligent players in the game" and predicted he would become a fine manager as a result. It was that game intelligence that made him such a fine substitute. And he has, of course, begun his managerial career superbly, winning the Norwegian league title with Molde, a side who had never before been champions.

Yet Solskjaer was never quite comfortable with the neologism "supersub", which highlights the paradox of the role. The better a player performs as a substitute, the more he feels he ought to be a starter.

In September, Cesc Fabregas, complaining about how often he was left on the bench at Barcelona, saying: "There's no such thing as a great substitute in the world of football. I couldn't tell you what makes a great substitute."

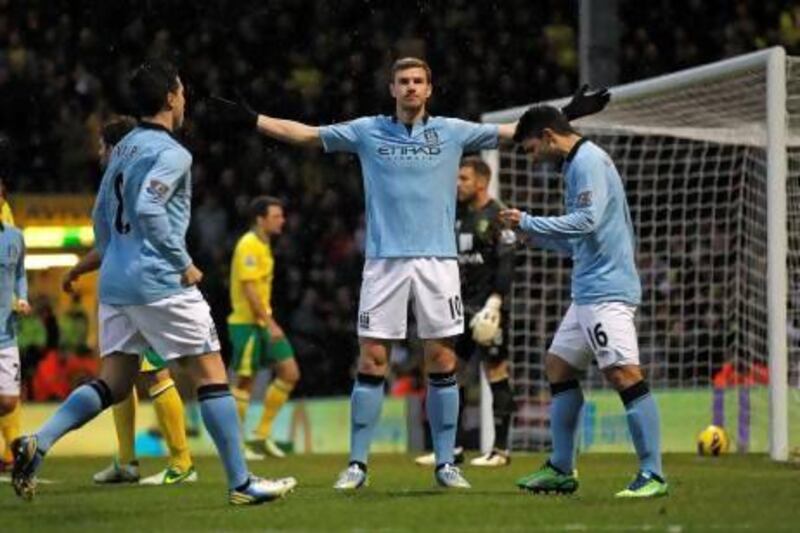

Or take Edin Dzeko: earlier this season he turned around a game at West Bromwich Albion that seemed to be going against Manchester City, but he immediately expressed dissatisfaction with his role: "I'm not a supersub," the Bosnian said. "I want to start games."

Yet this season he has scored a goal every 394 minutes when he starts games and every 44 minutes, 36 seconds when he comes off the bench. Manchester United's Javier Hernandez, similarly, scores every 44 minutes, 15 seconds as a substitute and every 248 minutes when he starts. Some players just seem to have an aptitude for coming off the bench.

The original supersub was David Fairclough, who sealed his reputation in Liverpool's epic victory over St Etienne in the European Cup in 1977.

One down from the first leg, Liverpool led 2-1 in the second and were going out on the away goals rule when Fairclough, only 20, was introduced.

Six minutes from time, he gathered the ball around 35 yards from goal, sashayed round a defender and finished calmly. His growing reputation as a player who could turn games from the bench was sealed. "I hated sitting on that bench, despite what people might think," Fairclough said.

"It was frustrating, horrible at times. At the start of my career, I was just grateful to be involved. But that changed, of course."

Yet there are signs that the mentality is changing. Both Arsenal and England have used Theo Walcott as an impact substitute, recognising how his pace is particularly troublesome to tiring defences.

Steve Clarke, the West Bromwich Albion manager, has a clear theory on how best to use his two strikers, Shane Long and Romelu Lukaku. Essentially he plays one for 60 to 70 minutes doing what he has described as "the dog work" and then sends on the other to capitalise on defenders' weariness in "the glory role" - an inversion of the usual perception of the part substitutes play.

In other sports, the ability of a player to enter a game late and make an impact is respected. Perhaps football, too, can learn to appreciate game changers, those quick and intelligent players who can be called upon to save a match.

After all, in films and comics the people you turn to in crisis are known as superheroes. Supersub should not be a term of abuse.

Follow us

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]