Football isn't usually something that springs to mind whenever Russia and Islam are mentioned in the same sentence. Indeed, despite Vladimir Putin's assertion that Russia is "a Muslim power", the planet's largest country and its fasting growing religion have had a complex, often violent relationship over the last couple of decades. From the horrors of the two Chechen wars to inter-faith tensions, there would seem to be no place for the world's favorite sport among the apparently endless conflict.

All this then makes the success of Rubin FC, from the capital of central Russia's Muslim-majority republic of Tatarstan, a surprising and welcome contrast to the unrelenting bad news. In 2008, seven years after winning promotion to the elite for the first time, the Kazan-based side unexpectedly ran away with the Russian Premier League title and are on course for a second successive triumph. Come autumn and the Champions League, Rubin will also look to become the first Russian club to make it out of their group for seven years.

The side's forthcoming Euro-pean adventure is also likely to act as a positive advert for Tatarstan, and by association Russia's 15 million or so Muslims, with the massive Qolsharif mosque that towers over Rubin's home stadium leaving TV audiences with little doubt as to the dominant faith in the region. The club's rise to such heights has been overseen by their notoriously taciturn manager and vice president, Kurban Berdyev, a devout Muslim from the former Soviet republic of Turkmenistan who prefers to give interviews to publications devoted to Islamic issues rather than sport papers, and whose after-match press conferences occasionally consist of little more than a single: "Glory to Allah, we won."

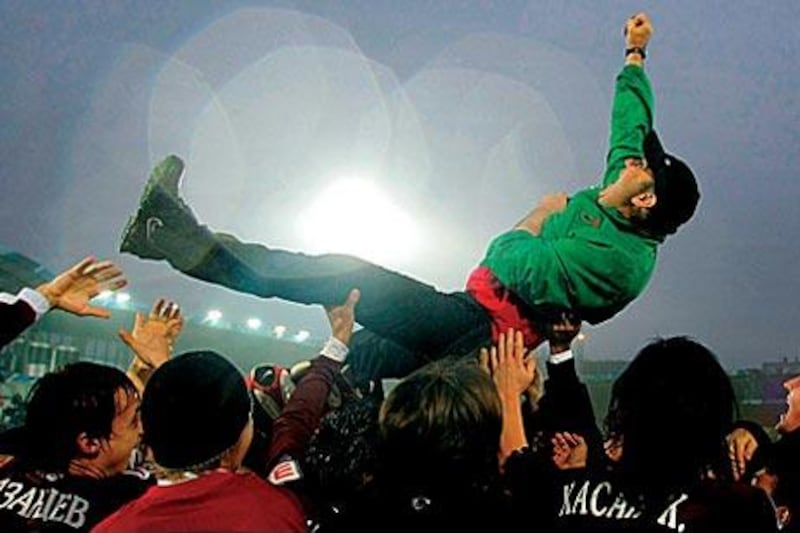

When he does open up on topics other than Islam, Berdyev's utterances are far removed from the usual footballese of your average coach. Upon the occasion of Rubin's title triumph, the 56-year-old local hero took the chance to speak of the importance of sport in modern Russia. "In the Soviet era, people believed in the Party, in the ideas of that age. But what do people believe in today? We're not so rich in ideas, right? But sport provides us with aims that can be achieved, one that allows those who share them to feel pride. In that respect, all the clubs in Russia are engaged in a very necessary activity - we are shaping the souls of children."

For a manager so concerned with Russia's younger generation, it is perhaps fitting that the image that dominates Rubin's strip is a winged, golden panther - the Tatar god of fertility and protector of children. That the panther is also the symbol of sponsors Taif, a wealthy regional oil, gas and construction company, is perhaps somewhat less apt. Still, the top is particularly nifty, and a boom in Rubin shirt sales cannot be ruled out when the Champions League rolls around.

Despite Taif's generous financial backing, the club's success has been achieved without big names, with Berdyev building his pragmatically defensive team on the rock of Russian midfielder (and Orthodox Christian) Sergei Semak, 33, a player almost as low-key and as thoughtful as his enigmatic trainer. Semak's career, most of which had been spent at CSKA Moscow, looked to be winding down when Berdyev brought him to Kazan last year, his solid performances earning him a recall to the national side in time for Euro 2008.

While Rubin's fairy tale would be unimaginable without Berdyev's tactical skills and transfer market astuteness, this is, after all, Russia, where allegations of political conspiracy and corruption are as commonplace as disputed penalties, and the club's success has also been linked to a Kremlin policy of reaching out to key ethnic regions in a bid to maintain the at times shaky unity of the vast Russian Federation.

In the early 1990s, oil-rich Tatarstan's 3.8million inhabitants looked set to split from Russia, with 62 per cent of voters, a figure slightly higher than the republic's Muslim to non-Muslim ratio, supporting independence in a referendum. Secession was eventually avoided after a broad form of autonomy was granted to the republic, and while long-serving President Mintimer Shaimiev has since seen much of his power taken back by Moscow, Tatarstan continues to reap the fruits of the Kremlin's vested interest in the region.

In 2008, Kazan was granted the right to call itself "Russia's third capital", after Moscow and St Petersburg, and state support is also visible in building and infrastructure projects, including the city's new metro system. The lid has been kept shut on the independence movement, for now at least. Such overt Kremlin backing led to inevitable speculation that Rubin's 2008 title-winning season, in the year of the club's 50th anniversary, was the result of high-level interference in the game, something that would, admittedly, not be a first in Russia. Others, many of them it must be said disgruntled fans from rival clubs, claimed that the side's triumph was partly due to the team "calling in" wins for games that they had thrown the previous season, a long-established Russian form of match-fixing.

While this season's continued good form has seen the allegations largely subside, it will surely take another title victory for all the suspicions to be laid to rest. As they continue their quest for title No 2, Rubin host Chechen club Terek FC on August 18, in a clash of the Russian Premier League's only two Muslim teams. Named after the river that flows past the Chechen capital of Grozny, Terek were formed in 1946 and failed to win a single trophy during the Soviet era. However, the club's significance goes far beyond the world of football.

In the mid-1990s, the team were forced to disband when federal forces rolled into the republic to put down a separatist movement. Hostilities ended in 1996 with a peace deal that granted Chechnya a brief de facto independence, and former Terek player Shamil Basayev, a notorious Islamic militant who would later plan the 2004 Beslan school attack, was appointed head of the Chechen FA. However, with Grozny in ruins after the heaviest bombing campaign since World War II, and the republic's players either dead or scattered across Russia, the bearded insurgent's role was largely a symbolic one.

In 1999, Russia launched a new invasion of Chechnya, and Basayev, quitting his post and grabbing his Kalashnikov, took to the mountains. Little more than a year later, with the second Chechen war officially over, the new pro-Moscow administration's sport ministry applied for permission to reform Terek. Despite the obvious hurdles, the Russian authorities, eager to prove the battle against the continuing Islamic insurgency was being won, sanctioned the club's re-entry into the third tier. However, holding matches in the burned-out shell of Grozny was clearly not an option, and the team were forced to play their "home" games some 150 miles away in the small town of Pyatigorsk.

Despite the club being bran-ded "Kremlin Terek" by most insurgents, reports suggest that Basayev remained loyal to his former side, trying to catch broadcasts of matches even during field operations. Indeed, Terek achieved the impossible in managing to unite the notorious rebel, Russia's public enemy No 1 until his death in 2006, and then-Russian president Putin in their passion for the club. "We all need to support Terek," the former KGB man said in May 2004, shortly after the team had lifted the Russian Cup, a major coup for the Kremlin and its attempts to prove that life in the republic was returning to normal.

While Putin's favourites went on to earn promotion to the Premier League at the end of the same season, the majority of the side's original Chechen players had been replaced by this stage with journeymen Russians and East Europeans. However, while homegrown footballers may still be thin on the ground, the club chairman is as Chechen as they get. In fact, Ramzan Kadyrov, a former rebel who switched sides in 1999, is also president of the troubled republic, inheriting both posts after the death of his father Akhmad Kadyrov in a May 2004 bomb attack.

A key Kremlin ally who has effectively been given free rein in the republic in return for his suppression of the separatist movement, Terek's chairman and his security forces have been accused of murder and abduction in Chechnya and beyond. In July, the human rights group, Memorial, claimed that Kadyrov was responsible for the execution-style shooting of activist Natalia Estemirova. Kadyrov denied the accusation, calling it "insulting". Interestingly enough, this was also roughly the same expression he used in May to describe match-fixing allegations levelled at Terek.

In March 2008, the authorities took the unexpected decision to allow Terek to play in Grozny. The move shocked the Russian football world. Even hardened fans used to following their teams to Siberia and other outposts were apprehensive at the prospect of a Chechnya away-day. There seemed little doubt that the decision to send players such as Andrey Arshavin to the former war zone was in part a Kremlin thank-you to keen football fan Kadryov for his loyalty.

The club's press attaché did have one word of warning for visiting supporters, though. However, he made no mention of insurgents or the local unpredictable security services. "It is not the custom to swear here," he said. "We would like guests to express themselves decently in public places." While Kadyrov may have image problems, he certainly seems to enjoy the unwavering devotion of the Terek players.

Just days after Estemirova's body was discovered, Terek defeated Zenit St Petersburg 3-2 in Grozny and the scorer of the winning goal, Bulgarian defender Valentin Iliev, pulled off his top and ran towards Kadyrov's private box, arms raised in homage like a gladiator of old. "I dedicate my goal to Ramzan Kadyrov," his compatriot, midfielder Blagoy Georgiev, whose fierce shot had opened the scoring, said. "We disappointed him with our recent cup defeat, and this win is by way of apology."

Terek were largely indebted to match referee Almir Kayumov for the "apology". The visitors were denied a clear-cut penalty in injury time, and ex-Spartak Moscow defender Alexander Bubonov suggested that the men in black were wary of giving decisions against the club in Grozny. He had a point. In August 2008, referee Aleksei Kovalev was assaulted in his dressing room at half-time and pitch side at the final whistle during a Terek-Lokomotiv Moscow match in the Chechen capital.

The Zenit victory also saw a St Petersburg female journalist claim to have been removed from her seat by Terek officials over her "short skirt and low-cut top". Although Terek later countered that she had been kicked out over her lack of valid press accreditation, the widely-reported story seemed to confirm that Islamic law had been de facto imposed in the republic. In late 2008, seven young women were found dead in and around Grozny, murdered, it was rumoured, over their immoral" behaviour. Shortly afterwards, Kadyrov encouraged Chechens to take second or third wives, even though polygamy is illegal under Russian law.

If then, by allowing Terek to hold matches in Grozny, the authorities intended to prove that Chechnya is returning to the fold, slowly transforming into just another Russian region after years of savage conflict, then this policy has clearly failed. High-profile football matches in Grozny merely serve to focus the public's attention on the fact that while Kadyrov's Chechnya may technically be a part of the Russian Federation, it is for all sense and purposes a separate state.

August's Rubin-Terek encounter is also then a meeting of two very different possible directions for Russia's Muslim republics. Where Tatarstan has cleverly reaped the benefits of Kremlin concern over Russian statehood, massive investment stimulating both economic and sporting success, the Chechen republic has imploded, locked in a vicious circle of insurrection and repression that is reflected in the troubled and complex history of its football team.

The game promises to be as fascinating off the field as on it. sports@thenational.ae