Manny Pacquiao leans back against a wall of gunmetal grey lockers and contemplates life without the very thing that has carried him there.

He has just concluded two hours enthralling those crammed inside Elorde Boxing Gym, a facility on the fourth floor at the Five E-Com Center in Manila’s Mall of Asia Complex, where the people congregate until there’s no space left.

There, as day made way for night, he ground through the routine and the rigour, a regimen all too familiar, as others stood wide-eyed at the talent that has made him world champion in an unprecedented eight different weight classes.

Now a member of the Philippine Senate, Pacquiao has altered slightly the output, more out of necessity than choice, to accommodate both his swollen schedule and milestone 40th birthday. The workout brings to a close another mammoth December day as a pugilist and a politician, a 1-2 punch that would floor somebody half his age.

But, for Pacquiao, one was once all he had ever known.

"I once left boxing for a while, but I realised I feel lonely, because I recognised that I didn't have boxing anymore, that I'm not a boxer anymore," Pacquiao says, eyes clear, voice sincere. "That's why I returned to boxing and keep on fighting. Because I feel that I can still fight, I can still fight good, and entertain people."

He enthralled during a hearty training session that preceded the interview, smiling and joking through the slog. Now, the clamour bursts through the walls from outside what feels like humanity’s most compact changing room, tucked behind the ring where Pacquiao sweated and swaggered. Blending the senate and sweet science is an arduous endeavour, but he seems to be coping. Thriving, even.

“It’s not easy,” Pacquiao says. “Every day you’re exhausted, mentally and physically. But it’s good. It’s a good challenge. I’m learning every day how you balance your schedule, how you discipline yourself.”

Changed from his boxing attire, Pacquiao sports a grey T-shirt, checked shorts, white socks and sports sandals. He turns 40 in five days, already has 69 professional bouts and 462 professional rounds on his Hall-of-Fame resume, yet his face bears little evidence of that toll. His hair remains jet-black, excepting the odd fleck of grey around the temples, caught here in the dim light. His diamond watch sparkles intermittently.

His T-shirt declares “faith will move mountains”, a reminder that Pacquiao preaches often of a talent God given, of a divine intervention that, allied with an otherworldly resolve, dragged him from sleeping in the streets of General Santos City to boxing immortality. Sat there, still somehow fresh, there doesn’t seem much else to attain.

“I have accomplished a lot; I accomplished my dream,” Pacquiao says. “Boxing is my passion and I’m happy to give honour and to be bringing honour to my country. I just want to keep on the path of boxing. I want to keep my name there at the top."

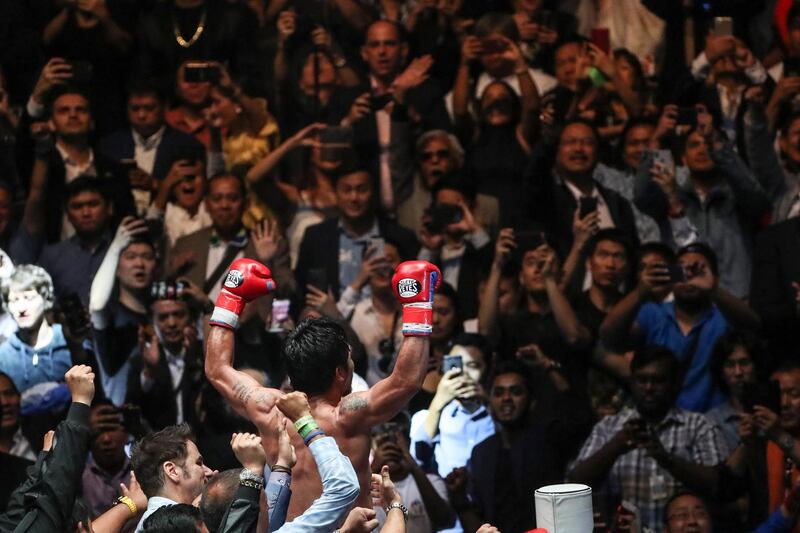

That mission has transported him to this potential crossroad. On January 19, Pacquiao returns to the glaring spotlight of the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, the venue he’s labelled his “second home”, for the first time in two years.

Adrien Broner awaits, a bombastic-but-brooding American who looms as arguably the grandest examination of Pacquiao’s powers since his record-breaking duel with Floyd Mayweather Jr in 2015.

Pacquiao has 60 professional victories under his mass of boxing belts, and vanquished venerable opponents such as Oscar De La Hoya, Erik Morales, Miguel Cotto, Marco Antonio Barrera and Juan Manuel Marquez. But his success last summer against Lucas Matthysse at the less-salubrious Axiata Arena in Kuala Lumpur earned him his first knockout in more than eight years, a stretch spanning 13 fights.

Where Matthysse, now 36, was arguably diminishing, Broner constitutes a clear and obvious danger. The Cincinnati native, with his fast hands and expert defence, has never been knocked out in 33 pro fights. He has three losses to Pacquiao’s seven and claimed titles in four divisions. Perhaps crucially, he is 11 years younger.

“I’m very, very confident for this fight,” says Pacquiao, somewhat predictably. “I want to give the fans a good fight and I want them to be satisfied with my performance on the night. And, of course, try my best to win convincingly.”

Those closest to Pacquiao, though, emphasise the threat posed.

“Broner’s a dangerous guy, a thinking fighter, a counter-puncher,” says Justin Fortune, the former heavyweight who has served as Pacquiao’s strength and conditioning coach since 2002. “But it’s not like we haven’t seen another Broner before.

“Everyone who fights Manny fights above their pay-grade, because it’s Pacquiao. Everyone who fought Tyson fought the best they possibly could, because they thought they were going to die.”

Pacquiao's career appeared to have drawn its last breath following his clash with Timothy Bradley three years ago, when he prevailed on points, but promptly announced his retirement. Seven months later, though, he returned, defeating Jessie Vargas before dropping a controversial decision against little-known Jeff Horn in July 2017. Irrespective of the contentious call, the loss indicated Pacquiao had crept well past his prime.

_____________

Manny Pacquiao beyond the ropes:

Part 1: A man who gives hope to the Philippines

Part 2: Turning 40 and no signs of slowing

_____________

Yet, last October, he signed with Al Haymon, the influential boxing manager and adviser whose Premier Boxing Champions series controls the welterweight division. Haymon holds all the keys. The hook-up with Pacquiao promises another few marquee nights before the closing bell eventually tolls.

“If you ask me, I can still fight two or three more years,” Pacquiao says, not quite defiantly, but convincing nonetheless. “Right now, what I feel is that I’m still OK. I’m not thinking that I’m 40 years old. I’m thinking that I’m early 30s or late 20s. Twenty-nine, like that.”

Revisionist math aside, the consensus among his team is that Pacquiao is a few fights from calling time on a distinguished career.

“This is the final chapter,” says Joe Ramos, chief operating officer of Pacquiao’s promotions company, a friend dating back more than 15 years. “It’s a good way to see him go. We want the best; we want to fight the best. Al Haymon and PBC, those guys have the best talent at welterweight and so we’d like the chance to prove Manny’s still the best fighter in the world.”

Still, the spectre of Mayweather Jr hangs in the air. Pacquiao collided with the American at MGM Grand on May 2, 2015, in the most lucrative bout in boxing history. It brought to an end one of the sport's great, drawn-out sagas. A month from the fight, Pacquiao tore his right shoulder, but requests to postpone the bout were denied. With an estimated $600 million generated, and the clash half a decade in the making, it was too late to delay. Three days after, and following a comprehensive defeat on points, Pacquiao underwent surgery. More than three years later, he seeks redemption.

“Obviously Floyd’s retired, but it’d be the best fight out there for us,” Ramos says. “I know Manny would love to have the chance to prove to the world that he was hurt during that time, and now he’s healthy. I know it’s really itching him to show the world he can beat Floyd.”

To lure Mayweather into a rematch, Pacquiao needs to notch another resounding victory, against Broner, most probably another stoppage. Broner was chosen with “Money” in mind, a similarly defence-first boxer adept too at landing verbal blows. He has been typically brash in build-up to January 19. Apparently, it has registered.

“We picked Broner because Broner is 95 per cent similar to Mayweather,” says Buboy Fernandez, Pacquiao’s best friend from GenSen, an ever-present during the boxer’s ascent to legendary status and now his head trainer. “That’s why Manny said we’re going to fight him. I asked him which one and he said, ‘The one who moves the same as him, who like him talks too much.’ And I said, ‘Mayweather and you? Rematch? That’s your tune-up fight there’. But Broner is a tough guy, a former world champion. We cannot underestimate him.”

That doesn’t concern Fortune. He has always been impressed by Pacquiao’s tunnel vision, his commitment to never peering beyond his next opponent. That said, Fortune adds, he is convinced Pacquiao wants to scratch that aforementioned itch.

“Ask Floyd, because that’s what needs to happen,” Fortune laughs. “Mayweather needs to happen, not us. I don’t know if Floyd will ever bark again and start up a fight. Who knows with Floyd? That’s up to him. That’s his business.”

As the nickname, “Money", suggests, or his garish displays on social media affirm, Mayweather’s business is fuelled by only one currency.

“You know what the carrot is, right?” Ramos says. “It’s a bunch of figures, a bunch of dollars, a bunch of zeros after that first number. That’d be the ultimate prize for Floyd.”

Maybe Mayweather represents the premium prize for Pacquiao. He is reluctant to spend much time discussing his old foe. But, when prodded, Pacquiao acknowledges that, even with all the belts and bounty, there remains a score a settle.

“That’s what I’m talking about,” he says. “There is a big possibility to have a rematch with Floyd Mayweather if I win this fight convincingly. Especially because we have the same promoter, Al Haymon. So it’s a big, big possibility.

“Let’s finish this Broner fight and then let’s talk about the next fight. And if there’s a rematch, there’s a rematch.”

As Fortune highlights, both are far from their vintage. Each has slipped the wrong side of 40 – Mayweather turns 42 next month – and while the undefeated Mayweather plays pantomime with MMA fighters and Japanese kickboxers, Pacquiao's boxing runs parallel to politics.

A congressman since 2010, in 2016 he was voted into the Philippines Senate, as one of 24 elected representatives in the governing body. Comfortable pushing bills like he used to push back boxing’s boundaries, he attempts to use his profile to help better his country.

“Politics is natural to me," Pacquiao says. "As long as I can explain my heart to people, I can explain my sincerity to serve people. I’m happy serving the people, helping them. Even my own money I spend for them. I know the problems. I have been there. We need time to answer the people and solve those problems.

“What surprised me most when I became a politician and a senator is a lot of promises, a lot of talking about the problems, but no action. And I’m a kind of person that I just want to gain more action.”

Given the paired vocations, his days are action-packed. Before the senate session concluded for Christmas, and with the Broner bout nearing, Pacquiao’s programme spanned 14-16 hours daily. Often, his schedule would begin at 6.30am and run until after 8.30pm. Surely, eventually, something will have to give.

“He just loves to fight – it’s in his DNA,” Ramos says. “It’s something you can tell, that at 40 years old, he’s still got the passion, still got the speed, still got the power.

“And he really believes it’s his way to unite the Philippine people. When he fights here, on Sunday morning there’s no crime. There’s no parties, no rebellions. It’s just everybody glued to the TV, cheering on the Filipino to win.”

Yet, ultimately, Pacquiao is fighting an unwinnable fight. However much he or his team protests, however polished and potent he looks on this shimmering December evening in Metro Manila, there is only so long he can push back against the caprices of age. Though he wears no gloves or robe, Father Time remains undefeated.

His inner circle is conscious of the biological clock. No matter the speed and power – Buboy insists the former is as quick as when Pacquiao was 25 and about to embark on a spectacular career, the latter more punishing – there is the realisation that boxing is full of ancients who railed against that inexorable slipping away.

“For me, not all the time you are back in the ring,” Buboy says. “Not all the time you are the Manny Pacquiao that people expects you to be. But I don’t want my friend to get hurt. I don’t. Two to three fights. That’s it, we’re done.

“We’re done with proving to the people who Manny Pacquiao is. Now eight-times world champion, the first boxer in history to become a congressman and a senator. As a friend, as a brother, as family, I don’t want him to get hurt. Two fights, that’s it, done."

Buboy and Joe and others have broached retirement with Pacquiao, but they all accept it’s not their decision to take. Pacquiao’s competitive urges burn bright still, witnessed by the multitude in Elorde, demonstrated during his near-daily games of basketball, or when he’s settled at the chessboard, or tackling crossword puzzles on his phone. Even now, the competition drives him.

“Being a fighter, being an athlete, distractions are always there,” Pacquiao says. “It depends how you balance it, how you control it. If you are given to total distraction, you will be affected. But if you control your schedule, control your time, manage yourself, it’s not a problem. Distraction is always there. It depends upon how you discipline yourself.

“If I feel something in my body that will affect my focus, my training, my style, I have to hang up my gloves and say bye-bye, I’m going to retire. That’s my plan.

"This is a blessing. A lot of fighters retired early in age, so this is a blessing that, at 40 years of age, you’re still a fighter and you can still fight.”

Pacquiao’s not simply fighting for himself. His team resemble a brotherhood, the majority there from the start, some picked up along the way as he extended far beyond the Philippines. They are welcoming, accommodating, genuine folk. They are not a burden, but, just as he does as a senator with his constituent countrymen, Pacquiao feels indebted to them.

“The people around me are relying on me, to also get jobs, to also help me,” he says. “I’m working for the best for us. Not only for myself, but for the family and for those around me.”

Pacquiao has been here before, weighing decisions regarding his family and his future, wrestling with the decision to hang up his gloves, with the loneliness that it stirred. Wife Jinkee and those closest have been down this road already. Boxing kept calling him back.

“They talked about that to me before, but I wanted to explain to them again. They understand,” Pacquiao says, leaning back against the lockers. “And, you know, one day I will make a final announcement for my retirement. But not yet. I'm not done yet.”