Stirling Craufurd Moss was quite simply one of the greatest racers that ever lived.

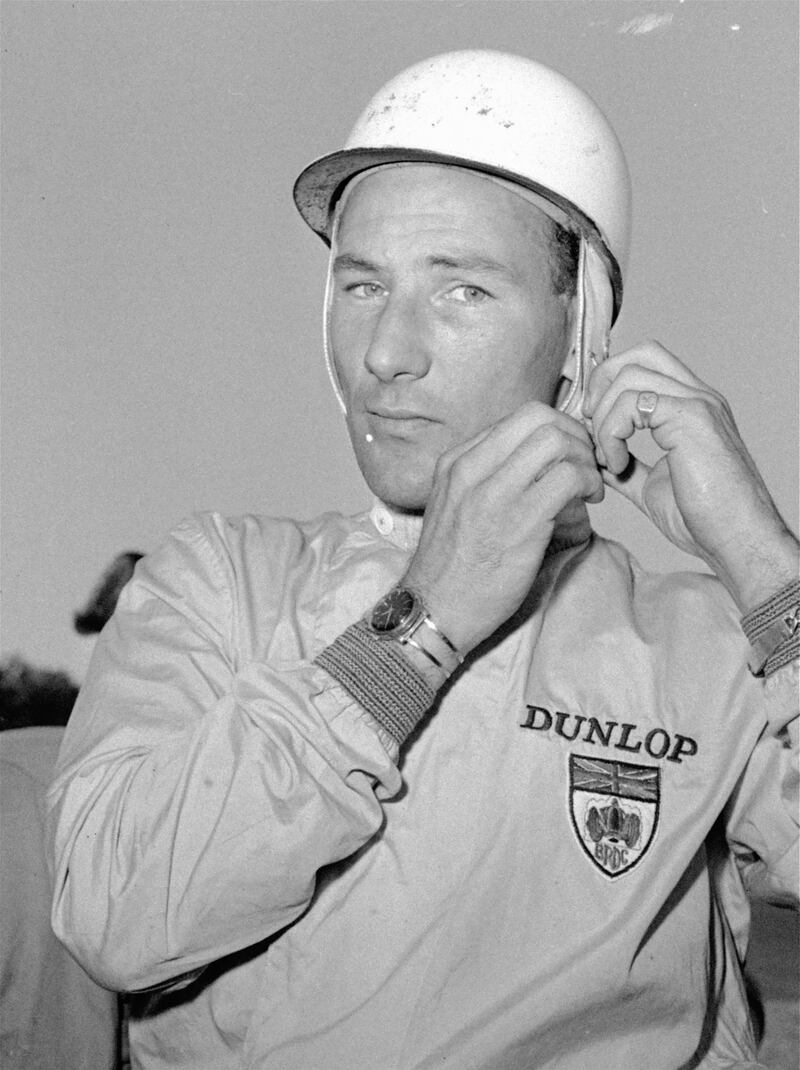

Overtly proud to be British – and race British – it remains more an indictment of F1’s points system that one of the sport’s greatest all-rounders carries the moniker as “the greatest driver never to win a world title”.

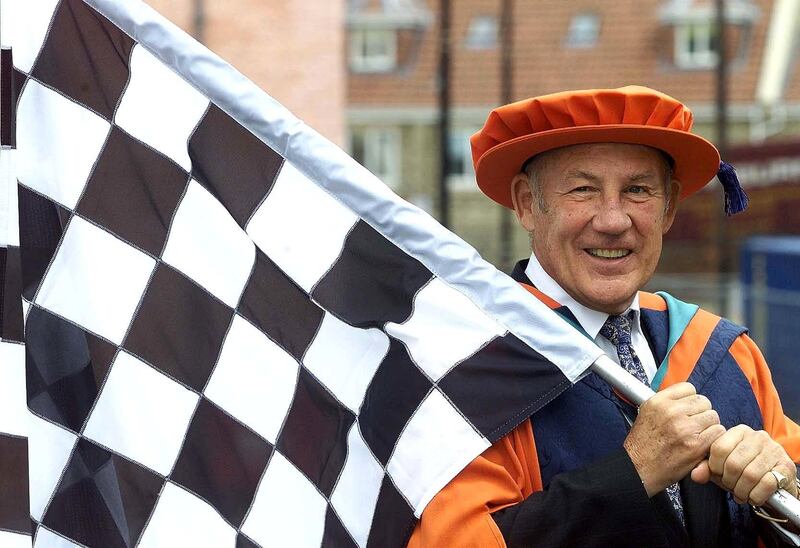

Knighted in 2000, nearly 40 years after he was forced to quit racing, Moss stands shoulder to shoulder in the pantheon with the sport’s greatest: Ayrton Senna, Juan Manuel Fangio and Jackie Stewart.

That he was runner-up four times and third on three more occasions in an F1 career that spanned just a decade is scant reward for one of the richest racing talents the world has ever seen.

Moss was more than a racer, more than a national British institution. He was a genuinely inspirational human being who’s life story was the stuff of movies. One who truly earned the title of legend.

Even the highlights do not truly capture a technicolour life lived in a monochrome age: the first British driver to win the British Grand Prix, first to win a British Grand Prix in a British car, first with a British team to win the F1 team’s championship, Le Mans winner, 16 time F1 winner, Mille Miglia winner. And so it goes on.

The only son of a well-to-do Bray dentist, Moss’ early success on horseback – so with one horse power – enabled him to put down £50 on his first racing car.

As his career blossomed Moss’ talent made him stand out but short for his age and perhaps because he was bullied at school, he combined ferocious speed with a gentle and jocular manner that won hearts the world over.

His career was ultimately defined not only by his speed but a meeting with legendary team founder, Enzo Ferrari, in 1951. Invited to Maranello to sign up, Moss made the journey only to discover he had been rejected in favour of a popular Italian. “A gentleman wouldn’t do that,” said Moss later, vowing never to drive for the Italian marque and strengthened his resolve ‘to win British’.

"Better to lose honourably in a British car than win in a foreign one," became his motto.

But his allegiance to British outfits and fast, but frail, British race machines did as much as anything to prevent him achieving the ultimate accolade.

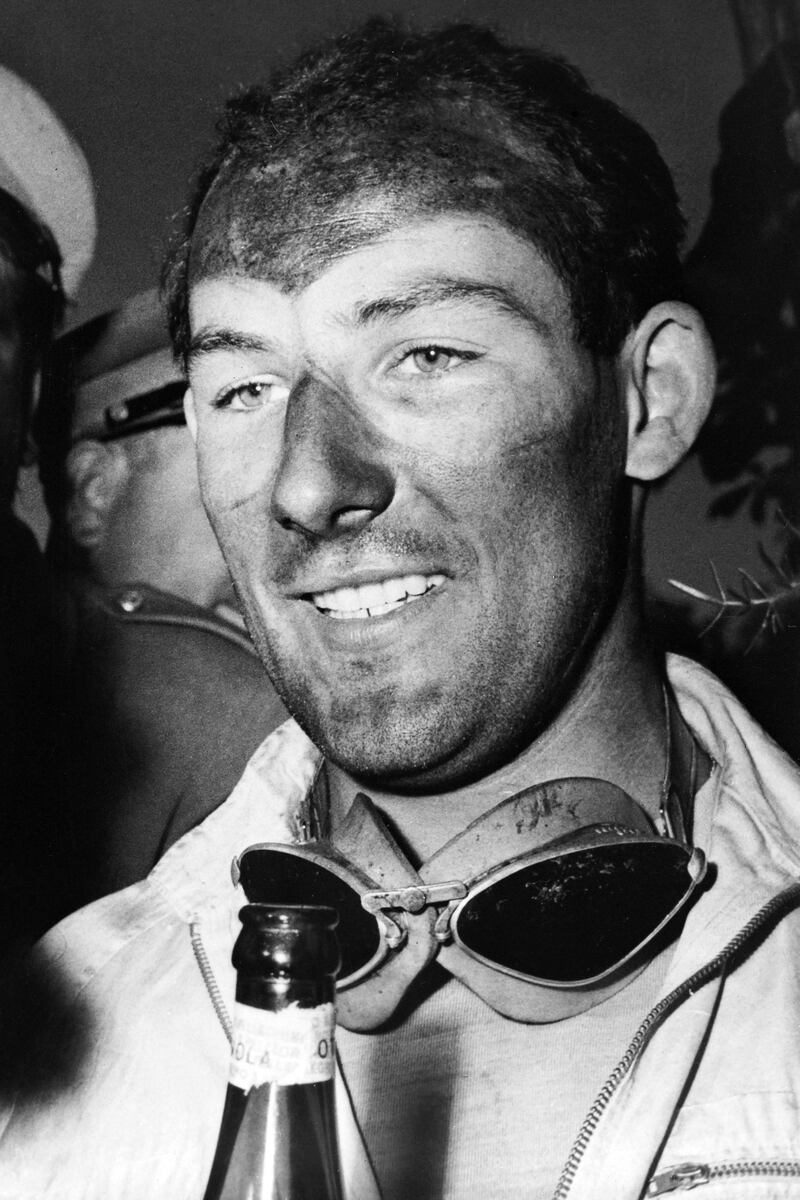

He still managed to win many of the world’s iconic races, triumphing at Monaco twice, Le Mans, and is famously remembered for his stunning 1,000 mile Millie Miglia victory across the mountainous roads of Italy, aged just 25, coming home 33 minutes ahead of the legendary Juan Manuel Fangio who became his mentor.

What set him apart, out of the cockpit, was his generosity of spirit. Arguing for rival Mike Hawthorn not to be disqualified in Portugal, three races from the end of the 1958 season, eventually was the difference that made Hawthorn the first English world champion.

Over his 14-year career Moss raced single seaters, sports cars, and rally cars and best estimates say he won 212 of the 529 events he entered, sometimes 62 races in a single year and, in total, 84 different makes. Among them were 16 F1 wins, a record at the time.

His ability to win in almost anything marked him apart. As the sport’s first post war professional racing driver, his earnings rocketed and he invested in a three-story Mayfair home he designed himself, crammed with gadgets that would have made James Bond proud.

With his established success came another call from Ferrari in 1961 and Moss agreed to compete in the Italian cars as long as they were fielded by his friend Rob Walker. It appeared to be the alliance that would finally ally Moss’ talent with machinery to give him his due.

But he never got to race it. A mystery smash at Goodwood before the start of the season ended his career. Death, a regular visitor to the paddock in his day was something Moss took a pragmatic approach to: “It’s something that frightens me but thinking about it doesn’t make it less likely, so I don’t.”

There are many Sir Stirlings to remember: the racer, smoothly sliding his car out of a corner, or the garlanded winner, blackened face white where his goggles had been, surrounded by scores of admirers. Perhaps stamping a cigarette out before he climbed into the cockpit.

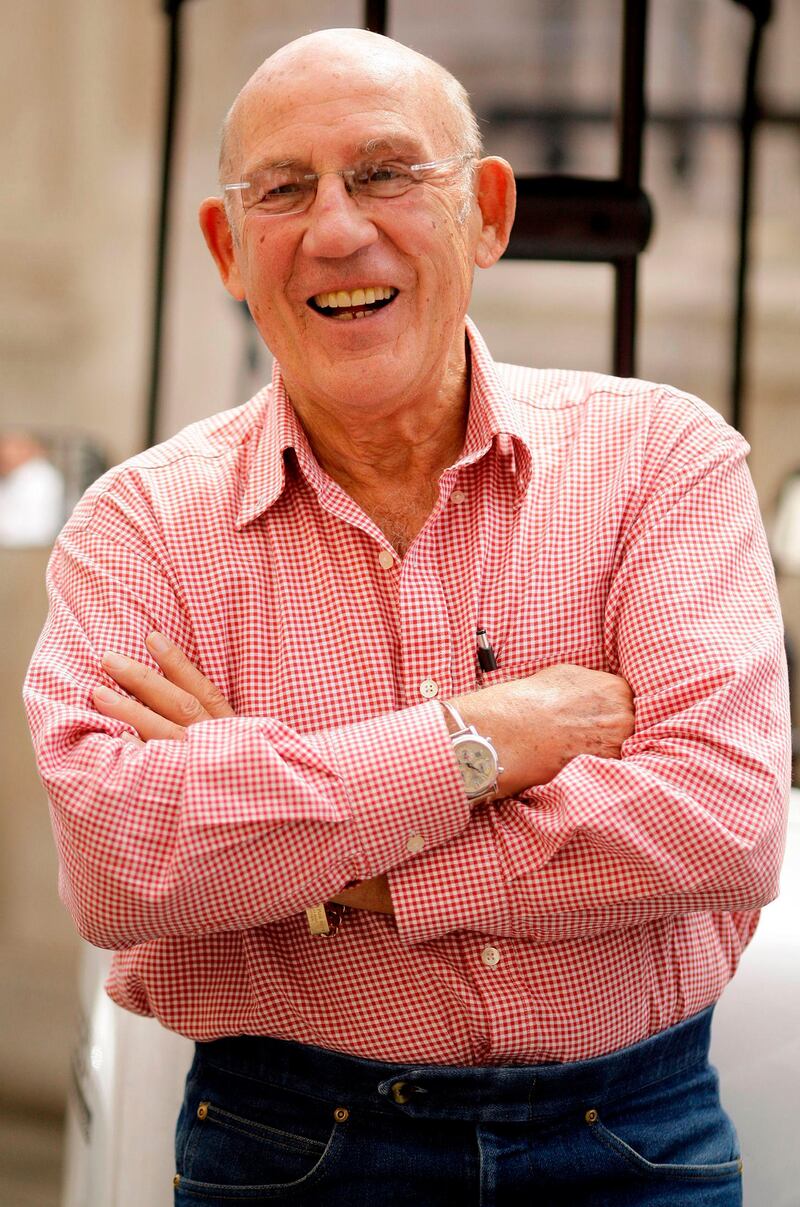

I choose to remember the elderly legend gingerly making his way across the paddock not so many years ago and when I asked him if I could put a few questions to him again he said: “Of course, dear boy”, opened his shooting stick, sat down right there and talked about life in motor racing.