Turn on the television, wait a few minutes and invariably you will hear of protests across Brazil.

What started as peaceful demonstrations evolved into police brutality, evolved into condemnation of police brutality, evolved into police restraint, evolved into looting, evolved into Brazil's president addressing the nation and urging calm.

Somewhere between one and two million people marched across 80 cities on Thursday evening. In Rio de Janeiro, the figure was in the region of 300,000. Yet were you to have gone for a wander along the long stretch of sand called Copacabana Beach at that precise moment, you might have noticed something unusual, but not unwelcome.

Under giant floodlights, you might have noticed an entire championship of beach football matches being played out. You might have witnessed a woman approach and jump and spike a volleyball so many times your own arm ached just watching. You might have noticed two men playing with wooden bats and a ball as if it were the middle of the afternoon and might have wondered if they had even realised the sun had set.

Anyone who believes Rio is in a state of widespread chaos need think again. Parts of Rio operate within a bubble and, on the surface, the Copacabana remains as close to a sandy utopia as one can imagine. It is this picture city officials want to promote as Rio gradually becomes the most prominent metropolis on the planet. As host city of the 2014 World Cup final and the 2016 Olympic Games, it is also this picture the majority of the world will see.

Yet the patience of residents, many of whom, because of high crime rates, feel obliged to live in compounds complete with barbed-wire fencing and round-the-clock security, has worn out. On Thursday night, not even 10km inland from the beach, demonstrations raged against the government, against the police and against the hypocrisy of spending billions on mega-events when the people endure primitive public services.

Fires burnt and shops were looted in a city that is home to more than six million people. Roads were blocked and traffic, already a source of strain for so many residents, was brought to a standstill. Grievances, of which there are plenty, were aired.

A banner seen earlier this week read: "We don't want a country that is beautiful only to gringos", while protesters taking part in a sit-down protest in Rio's Leblon district on Friday night could be heard chanting: "We don't want the World Cup, we want education and health."

Both assertions sum up the issue well. Rio – like much of Brazil – is readying itself to welcome the world, but it is inhospitable to its own people.

Tourists who want to lie on the Copacabana will find a city perfect for their purpose, yet the residents who need to live and work here are faced with crippling traffic, poor health care and a shameful education system.

Jorge Tagarro, a 63-year-old part-time tour operator who has driven taxis around the city since 1974, gave his verdict. "For tourists, no problems. Rio is fine," he said, as he sat in his car amid a traffic jam on the way to the Botafogo district of the city. "The Maracana is finished, the hotels are here, the people will come. The only problem is the traffic – we have too much."

The tourist bubble is intact for now, but the infrastructure to deal with the expected influx is not in place. Trains are crowded, buses are unsafe and there are concerns the city's two renovated airports will not be able to cope with the demands. Tagarro said he has noticed no upsurge in tourists during the Confederations Cup, but next year will undoubtedly be different.

According to Brazil's tourist board, the number of annual visitors to Rio is expected to rise steadily from 1.4 million to 3.3 million by 2016. Unless things change markedly in the next 12 months, there will be a lot of waiting around at the World Cup.

Vicente del Bosque, the coach of Spain's national side, has already raised what he called "a minor complaint" regarding the length of time it took for the team bus to get to the Maracana. When pushed on the subject, he remained diplomatic, adding: "It is not easy in cities like Rio, where transportation is not so easy."

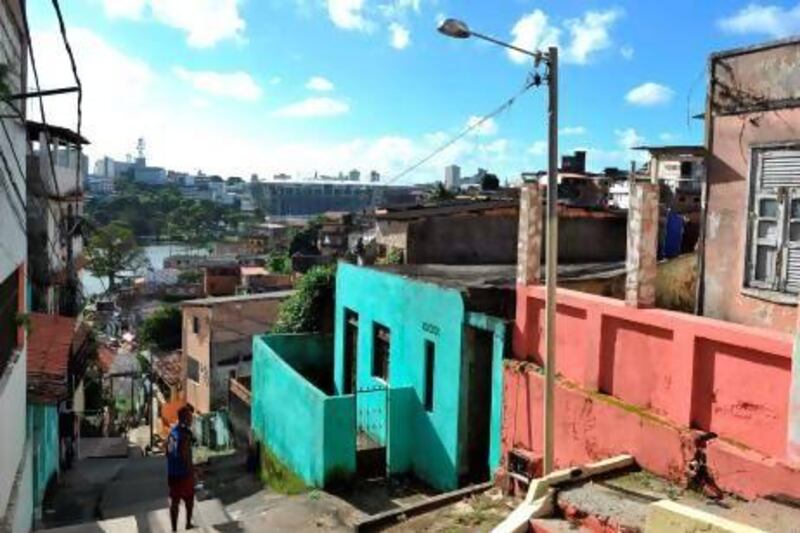

It is a similar story with crime. Many of Rio's notorious favelas have been pacified, but critics say the drug dealers who were operating in the shanty towns were simply relocated further from the city. The problem is not fixed; it has merely been swept under the carpet.

What happens when the focus switches away from Rio after summer 2016?

Rio has 12 months before the first of its two sporting showcases. The protesters are making themselves heard, but actions must be taken by the city.

Officials are being urged to improve residents' lives rather than tourists' holidays. Whether they listen will determine whether the popular picture of Rio as a sandy paradise remains merely a facade for foreigners or whether residents will feel any benefit of living in the most prominent city in the world.

Follow us

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]

and @gmeenaghan

[ @gmeenaghan ]