‘Obor” is not the name of an ancient king or kingdom, but it does resonate with an ambition imperial in its scope.

Obor – One Belt, One Road – is China’s “new Silk Road” and is spinning a web of connectivity by sea and land across Central Asia and into Europe. Its ports, pipelines, railways, roads and airports are a priority for Beijing.

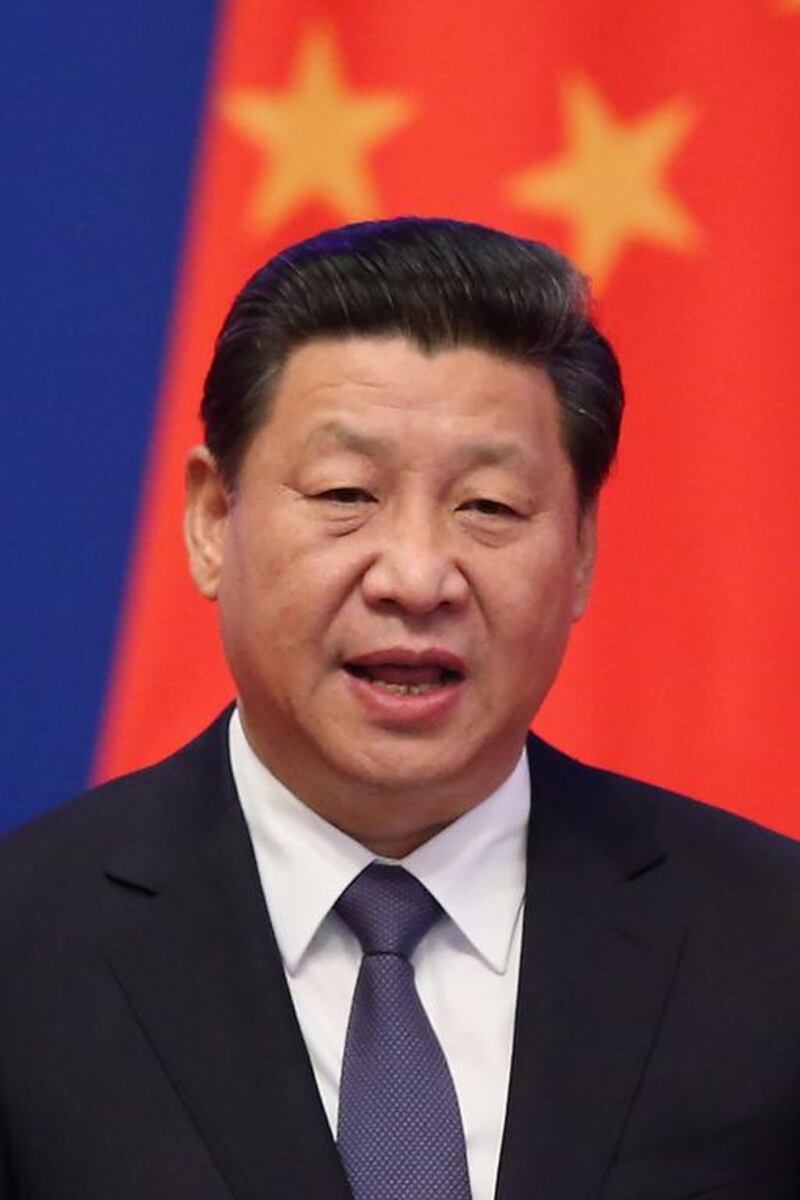

Launched by president Xi Jinping in 2013, it’s a vision that in its potential exceeds that of the Marshall Plan. Chinese officials are, however, quick to downplay such comparisons, for two reasons. The plan that helped Europe emerge from the ravages of the Second World War, they say, was Washington’s way of rewarding friends. Obor is non-political, they claim. Secondly, it involves much more money. The Marshall Plan in today’s value amounted to less than $100 billion (Dh367bn). Some estimates put the value of Obor projects now being built at just less than $1 trillion.

Obor is already extending Chinese commercial influence and reducing the Chinese economy’s dependence on investment in infrastructure at home, and allows it to export some of its vast excess capacity in steel and cement.

We have reached a tipping point, the significance of which was lost in many commentaries. In 2015, Chinese investment overseas outstripped foreign direct investment in China.

China’s outbound direct investment that year increased 18 per cent to $145.7bn, compared to $135.6bn coming in as foreign investment. China has emerged as a net exporter of capital.

Obor has money. In 2015 the Chinese central bank transferred $82bn to banks for Obor projects. A Silk Road Fund worth $40bn was given the green light by China’s sovereign wealth fund and the government set up the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank with $100bn of initial capital. While not formally part of Obor, the bank approved loans at its first general meeting for roads in Pakistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

Obor is far from complete but it is functioning, goods are being transported to Europe by land and sea. Overland trade from China to Europe mostly uses the northern route through Kazakhstan, Russia and Belarus. More than 1,250 trains made this journey in 2015, carrying 47,400 containers – a 40-fold increase from 2011. But is still at an experimental stage.

The plan involves about 60 countries, though an exact number is hard to pin down. But this vagueness does not diminish its importance. Beijing has three major stated goals: the opening up of China’s west, establishing a moderately well-off society by 2020 and a prosperous one by 2050. This is dependent on the success of Obor.

Beijing predicts that the new Silk Road will allow China to extend and showcase its soft power both culturally and economically. We are in a “period of strategic opportunity” up to 2020, according to the Beijing leadership, notwithstanding the remarks from American president-elect Donald Trump or territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

The global security environment, they believe, provides opportunities for China to extend its global power without risk of war. It also harks back to, and provides a timely reminder of, China’s more glorious past. Mr Xi’s presidency could well be determined by how successful it is.

Finally, Obor can shift the axis of world trade. Pacific and Atlantic trade is dominated by the United States. Obor considers Asia and Europe as one market, and suits Beijing’s preference for cutting out the middleman.

Much can still go wrong. Russia may not always favour such a powerful Chinese presence in its own backyard. A credit crackdown in China could diminish funding for overseas investment. The security situation may not be so benign.

But it is worth noting, just before the Trump presidency begins, that China’s leadership horizons extend beyond fantasies of building a wall.

Tom Clifford is a journalist in China