‘You are going to meet the George Clooney of Cuba,” a friend of mine told me as we drove slowly from the upscale Havana neighbourhood of Vedado to the Marina. You can only drive slowly in a 1948 Ford with a 1990 Toyota engine installed under its bonnet, but you have to talk pretty loudly to overcome the sound of a 70-year-old car creaking along.

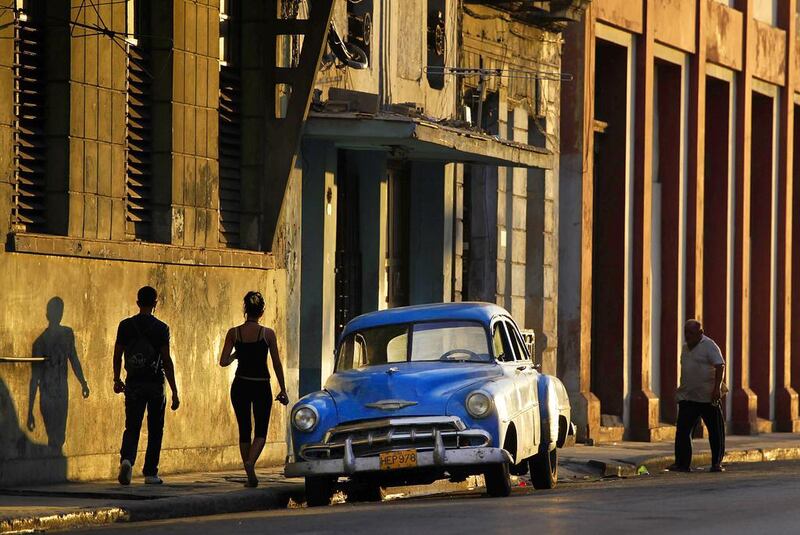

Many of the cars on the road in Havana are American classics – imported before the Castro-led revolution of 1959 – and have been tinkered with and reconstituted for decades, thanks to the United States-led trade embargo and the import restrictions of the Cuban government.

For an American in Cuba, this means that every taxi looks and feels like a time machine, and sputtering around Havana at night in an old American car could make you think for a moment that you’re in an old black-and-white movie. Except for the engine roar.

“I’m sorry,” I asked over the noise of the 1948 Ford. “Did you say the George Clooney? Of Cuba?”

She nodded. “He’s also the Harrison Ford of Cuba and the Tom Hanks of Cuba. And, in some of his movies, the Will Ferrell of Cuba.”

Cuba is a small island nation, of course, so movie stars here have to do double or triple duty. Jorge Perugorria, the man we were driving to meet, has been an internationally-known actor since he burst onto the worldwide stage in Fresa y Chocolate (English title: Strawberry and Chocolate) – a romantic comedy with political overtones – that was nominated for an Oscar in 1994. He’s also been a screenwriter, director, producer and a kind of godfather to the Cuban filmmaking community. (See what I mean about doing triple duty?)

I was meeting him because, for the past two years, I’ve been trying to get a television series produced that takes place in Havana and Miami. Here’s the pitch: a sharp and all-business female FBI agent (think Salma Hayek, think Penelope Cruz) is investigating a mysterious murder in Miami and the trail leads to Havana. She teams up with a Havana police detective (think Gael Garcia Bernal, think Diego Luna) and the two begin an uneasy and often acrimonious partnership. They solve the crime, but in the process they discover that their two countries – enemies for decades – have a lot of unsolved crimes and unfinished business between them.

So they decide to continue working together, mostly without notifying their higher-ups, to help bridge the gap between the two countries.

And, yes, they fall in love. But they argue a lot about everything, and each blames the other’s country for the troubles that exist in the region. What we say in the entertainment business is “sparks fly”, which is another way of saying: two attractive people fall in love despite themselves.

But to reiterate: it’s a romantic mystery show. It will take place in Miami and Havana and involve some great music, cigars, sultry tropical atmospherics, classic American cars, snappy dialogue in English and Spanish, and (I hope) it will be a crowd-pleaser from the northernmost part of North America to the southernmost part of South America, which is a pretty great market.

When I pitch the series, this is usually where I stop and wait for whomever I’m pitching to – a financier, a network executive, a studio president – to nod and smile and say, “This sounds great!” (Feel free, by the way, if you’re any of those – or know any of those – to pass this column along. As we say in Hollywood when we have a project to sell: I’m open for business.)

In Cuba, though, I modified the pitch. My guess was that the people I was talking to – actors and producers like Perugorria, government officials, Cuban media hipsters, police detectives and scattered low-life criminals – would all be irresistibly drawn to the larger themes of the series.

I hit that pretty hard in my introduction: this is a story of two countries, two different systems, decades of animosity and political intrigue. I’d add that in success the series would have a huge audience, but it would also help reconnect two countries that are closer than 150 kilometres.

As I sat with Perugorria, on the terrace of his seaside house, I wound up my presentation by suggesting that the series could be the first of many, and could be the beginning of more collaborations between the film businesses of both countries.

He, like most of the Cubans I met, nodded politely to all of my grand talk. And like everyone else, he had only one question: “It’s a love story, though, right?”

“Yes,” I said. “It’s basically a love story.”

And then he smiled widely and pointed at me, as if to say, “Don’t overthink it.”

Which are always wise words to hear, but especially when a project is just getting off the ground. A television series isn’t about big themes. It’s about people, specific people, who the audience wants to watch fall in love.

Rob Long is a writer and producer in Los Angeles

On Twitter: @rcbl