In recent weeks, the Indo-Pacific maritime domain has come into focus due to four developments with one common strand: China.

The most visible of them all has been the tense military stand-off between India and China along the contested Line of Actual Control, the 4,000-kilometre loose demarcation line that separates territories controlled by the two countries. An often articulated view is that, while naval power will not have a bearing on what is happening in the high Himalayas between the two Asian giants, it is a leverage that Delhi could consider using in order to manage an assertive Beijing.

The other three events pertain to reports recently released by the US Department of Defence and the German foreign ministry, as well as a China-Russia joint communique.

Assessed together, these documents point to the emergence of the Indo-Pacific as a domain for competition and a degree of contestation among the major interlocutors: China, Russia and US. This exigency would also hold a strategic and security relevance for India and other littoral nations of the Indian Ocean.

The world is in a state of uncertainty and flux due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and the geopolitics, in all likelihood, will be played out in the maritime continuum of the Indian and Pacific oceans.

The US DoD report and its naval/maritime focus on China is stark. The summary is that the People's Liberation Army Navy currently has more ships and submarines than the US Navy – 350 versus 293 – and that Beijing is determined to expand its footprint across the Indian Ocean. It notes that, in addition to the base in Djibouti, the Chinese military is seeking additional facilities in Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Kenya, Seychelles, Tanzania, Angola, and Tajikistan. Clearly, the geographical spread is expansive.

China’s determination to consolidate its position in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) has its own strategic considerations, and this is subsumed in what Beijing refers to as the "Malacca Dilemma" – the fact that China is dependent on the sea lines of communication for its trade and energy requirements. Beijing is also cognisant of a centuries-old tenet that, for a major power to be truly credible, it must be able to maintain effective military presence in two of the world’s navigable oceans at will.

It is evident that the US, which enjoys its position as the No 1 military power, is determined not to allow China to displace it in a routine uncontested manner.

This framework illuminates the relevance of India in the geopolitics of the IOR, for it is in a favourable orientation due to geography and naval pedigree. While India’s naval/maritime capabilities are more modest than those of the US and China, the two bigger powers are aware that their respective geopolitical aspirations and anxieties specific to the IOR can be significantly impacted by the posture that India adopts.

Currently three major non-littoral powers that have a visible military presence in the IOR are the US (in Diego Garcia), France (in Reunion) and China (in Djibouti). It is also instructive that Germany has now identified the Indo-Pacific as a domain where it plans to take greater interest than it has in the past.

Speaking at the release of his government's report, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said: “We are sending a clear message today – the Indo-Pacific region is a priority of German foreign policy. Our aim is to strengthen our relations with this important region and to expand our co-operation in the areas of multilateralism, climate change mitigation, human rights, rules-based free trade, connectivity, the digital transformation and, in particular, security policy."

Mr Maas further added that Germany wants to help shape the order in the Indo-Pacific so that it is “based on rules and international co-operation, not on the law of the strong". The allusion to China is unstated but evident.

Japan is also a stakeholder in the IOR. Shinzo Abe, who recently stepped down as prime minister, is seen as the prescient leader who first envisioned the confluence of the Indian and Pacific oceans as one strategic space. His country is a part of the "Quad" grouping that also includes Australia, India and the US – a cluster often referred to as a concert of maritime democracies committed to a free and open Indo-Pacific space that would be rule-based.

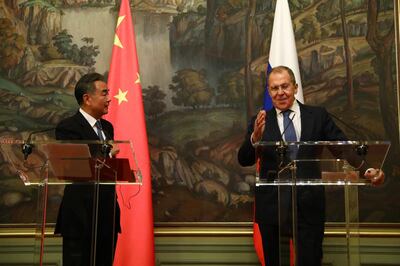

There is, however, an alternate formulation and a strongly held viewpoint that was articulated in Moscow at a meeting last week between the foreign ministers of China and Russia.

Their joint communique said: “We noted the destructive character of Washington’s actions that undermine global strategic stability. They are fuelling tensions in various parts of the world, including along the Russian and Chinese borders. Of course, we are worried about this and object to these attempts to escalate artificial tensions. In this context, we stated that the so-called ‘Indo-Pacific strategy’, as it was planned by the initiators, only leads to the separation of the region’s states, and is therefore fraught with serious consequences for peace, security and stability in the Asia-Pacific Region.”

For India, this is an anomalous development. It is because Delhi is a part of different groupings that place it under the same umbrella with Beijing and Moscow – the Russia-India-China trilateral grouping, Brics and the Shanghai Co-operation Organisation. Curiously, India was at the Moscow meeting where the China-Russia bilateral statement was issued.

In other words, squaring this nettlesome Indo-Pacific circle – even as it strives to retain its strategic autonomy along the troubled LAC in the Himalayas – will require India exerting a great deal of skill and diplomacy.

C Uday Bhaskar is director of the New Delhi-based think tank Society for Policy Studies