Egyptians are enjoying an unusually festive month, with the Islamic, Coptic and Jewish New Years all coinciding. This has prompted many friends to send out messages wishing each other good health and happiness. Granted, there are only a handful of Egyptian Jews still living in Cairo now, but these events have still made me pause to reflect.

Seventy years ago, my father was born in Aleppo, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, situated at the tail end of the Silk Road. Its location between the Mediterranean Sea, Asia and Mesopotamia made it an important hub for merchants across the globe, bringing silk from Iran and spices from India to its khans and bazaars, and transporting the city’s soap and fine textiles abroad.

My father, the eldest of seven children, grew up in the middle-class neighbourhood of Jamiliyeh in the 1940s and 1950s. He walked every day to the College des Freres Maristes, a French school run by priests in affluent Muhafaza. He told me that he used to attend mass on Sundays, as many of his friends did. Records available online show that at the beginning of the 1949 school year, the institution boasted eight different religious sects among its 80 students, and only four of its 67 Syrian students were Muslim.

My father was born into a traditional Sunni Muslim family. His grandfather, Hajj Tawfic, was a well-known religious figure in the city and often led prayers in the main Umayyad mosque, whose ornate Seljuk minaret was destroyed in the conflict earlier this year and is now subject to a reconstruction project by Bashar Al Assad's regime. As a child, my father accompanied him on Fridays to take part in the weekly grand prayer.

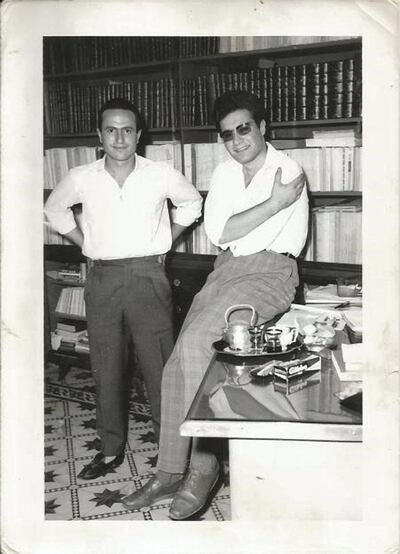

Between my father and Hajj Tawfic was my own grandfather, Fouad, a secular intellectual, a poet, writer and radio broadcaster who was refined both in his manners and his speech. Born in the 1920s, he married a beautiful woman, Fatima, from Hama, a neighbouring Syrian city later made infamous by the 1982 massacre, in which up to 40,000 people were killed for rebelling against Hafez Al Assad’s Baathist government. She was 16 years old when she moved to her husband’s hometown. She was a loving wife and a devoted mother who was uncompromising on one issue: maintaining her beautiful hair, which she entrusted to the magic hands of her Armenian coiffeuse, Sylvo.

Central to my father’s upbringing, and probably the most important person in his early life, was his nanny Rachel. Rachel was a young Jewish woman who, like many of her age, had received a French education at an all-girls school run by Franciscan nuns in Aleppo and later found a job as a governess. She quickly developed a particular fondness for my father and poured all her energy and love into raising him as if he were her own.

The creation of the state of Israel in 1948, the wars of 1956 and 1967, the loss of Arab territories and lives, and growing hostility towards Jews in the Arab region forced many Syrian Jewish families to leave behind friends and neighbours of all religions. Most moved to the US and Latin America.

The current war in Syria has further galvanised society around religious and sectarian lines, breaking apart what many Syrians had always proudly considered an intricate, yet durably interwoven social and religious fabric. Even if Syrians had always been aware of each other’s religion or sect, that had never been a reason for rancour. The unwritten rule was to avoid discussing religion and politics in the same breath and to avoid inter-faith marriages, although there were, of course, numerous exceptions to the latter.

There is no starker illustration of how fragile that social fabric really was than the sad reality of Syria today. Aleppo has lost most of its Armenian inhabitants during the present conflict, a tight-knit community that has made its home in the ancient city for centuries. Once 60,000 Armenians lived in Aleppo alone, but now it is reported that only 15,000 remain in the whole country.

The authoritarian Baathist political system, in place since 1963 in Syria, rests on Arab socialist and secular ideologies, and the nation's constitution maintains that the state shall respect all religions and protect the personal status of all religious communities. But while Christmas festivities and Ramadan celebrations had become more visible in the decade preceding the conflict, a series of tragic sectarian incidents since the outbreak of the conflict in 2011 show that inter-communal mistrust had been building for much longer.

Stories of neighbours turning on neighbours make older stories of inter-communal harmony sound like those of an alternate reality. Large-scale displacements that have occurred in big cities such as Damascus, Aleppo and Homs not only alter the nature of those places, they also highlight a tragic outcome of this conflict: the fact that less than one century ago, my Sunni-born father went to a Jesuit school and was raised by a Jewish nanny, and that this will never happen in Syria again.

Political violence in Syria, like that in Iraq before it, has been fuelled by regional and international players who have skillfully used sectarian discourse to rally support. Mr Al Assad's regime might have made military gains, but the only genuine victory in this conflict would be to give Syrian people hope that they can all still belong to one country, regardless of their beliefs or ethnicity. Amid a war that has killed nearly half a million people, though, it has become extremely difficult for voices that once called for democratic transition and equal citizenship to prevail. Now, I cannot help but feel that the long-held wish to return to my father's Aleppo has become an impossible dream.

Tamara Alrifai is a Syrian columnist and human rights advocate living in Cairo