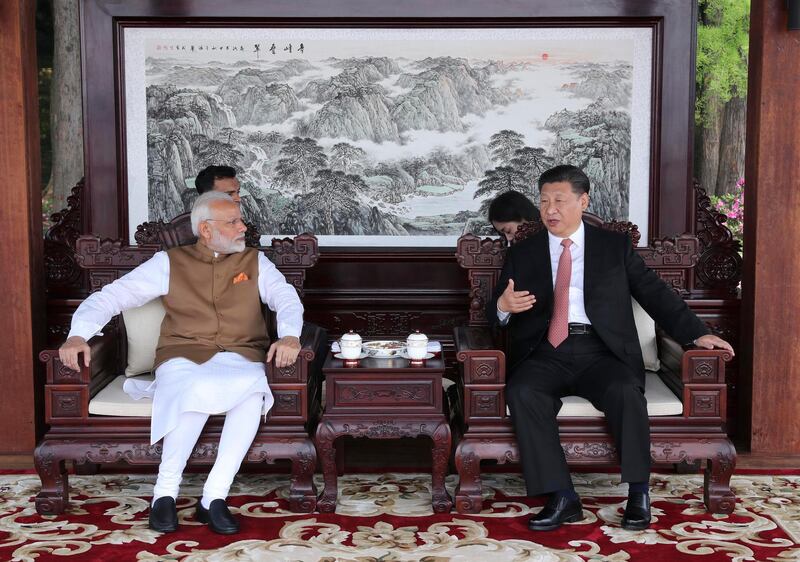

The two days spent together in Wuhan by Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi were an investment in the strategic stability of rising Asia in the 21st century.

Their informal summit demonstrated how Asia's chief strategic rivals need not let their 20th century differences over the demarcation of their shared Himalayan border overly impact their inevitable emergence as the world's two largest economies.

While the leaders’ extended conversation did not yield any unexpected progress in bilateral disputes, as was expected, it did yield a promise to jointly execute an economic project in Afghanistan.

Symbolic as the agreement might be, it has “immense importance for both cooperation in Asia and peace in Afghanistan” and constitutes “an implicit rebuke to both the US and Pakistan” for continuing to pursue redundant policies in Afghanistan, according to the leading South Asia expert Barnett Rubin.

By seeking to impose self-interested outcomes, American and Pakistani policymakers have served only to deepen the destabilisation of Afghanistan, renewing its attractiveness to anarchist forces like ISIS as a potential base from which to perpetuate terrorism across Asia.

By working against such a common threat, Mr Xi and Mr Modi have wisely chosen to prioritise the exclusion of non-state elements from their broader geostrategic competition.

The specific message to Pakistan from its close ally China is all the more clear. As Mr Rubin said: “China not only recognises but wants to cooperate with the Indian presence in Afghanistan.

“For years, the Pakistan military has rationalised its support for the Taliban and other pressures on Kabul by citing the threat posed by the Indian presence."

This reinforces the advice Beijing has been offering Islamabad since they agreed in 2015 to establish the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the showcase economic development programme of Mr Xi’s favoured One Belt, One Road Initiative.

With $27 billion of "early harvest" projects either already completed or close to being so and another $33 billion in the works for the period up to 2030, CPEC is undoubtedly the economic game-changer for Pakistan that both governments claim it to be.

But that potential is unlikely to be realised if Pakistan’s policymakers, in particular its domineering military, do not change their “friend or foe” mindset on relations with its neighbours.

China has advised that this approach is inherently counter-productive because it holds Pakistan’s economy, potentially one of the world’s 20 biggest, hostage to strategic goals which time has proven to be unachievable. Pakistan cannot unilaterally impose its will on the US in Afghanistan any more than it can force India to capitulate on the Kashmir dispute and vice versa.

____________

Also by Tom Hussain:

[ Asma Jahangir has died at a time when her legacy of common sense and decency is needed most ]

[ After four deadly attacks, the only certainty in Afghanistan is more of the same ]

[ Trump's ultimatum puts Pakistan firmly in his crosshairs ]

____________

Instead, such thinking has practically invited punitive measures from Pakistan’s perennial rival, the US, and provided India and Afghanistan with ample diplomatic fodder with which to isolate it.

China’s choice of Pakistan for its biggest One Belt, One Road Initiative programme, on the other hand, was posited by Mr Xi in 2015 as a grateful acknowledgement of its role in ending the communist state’s international isolation in 1972.

Beijing has repeatedly counselled that it cannot indefinitely shield Islamabad from the fallout of unsustainable policies. In February, it allowed the proverbial penny to drop by withdrawing its opposition to a US-led, India-backed motion to place Pakistan back on the anti-terrorist financing watchlist of the Financial Action Task Force, an international watchdog.

The longer it ignores its friend’s advice, the less likely Pakistan would be able to influence the ultimate political outcome of its disputes with the US, India and Afghanistan.

Instead, its ability to maintain strategic weapons parity with India – courtesy of Chinese transfers of technology since 1989 – would likely be compromised by the growing list of financial sanctions that pariah status is attracting.

But Mr Xi’s example is not the only one Pakistan should be looking to emulate. By negotiating with his Chinese counterpart in the aftermath of the last year’s humiliating Himalayan standoff, Mr Modi too has demonstrated his ability to learn from the folly of chest-beating jingoism.

Unfortunately, Pakistan is in the wrong state of mind to thoughtfully react to the dilemma posed by the Wuhan summit, or to US pressure over Afghanistan.

Instead, the competing arms of the Pakistani state remains engrossed in squabbling over who controls the domestic decision-making process. In the face of such blinkered partisanship, any diplomatic rethink is more or less impossible.

Tom Hussain is a journalist and political analyst in Islamabad