Land has always been central to the Palestinian national identity.

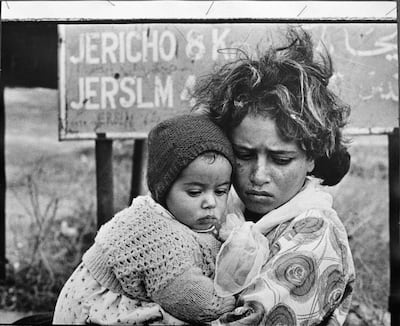

I learnt this lesson in 1971 when I spent time in Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan collecting people’s stories of the Nakba. Their memories of the homes and lands that they left behind, their deep longing to return, and their determination to keep alive their village culture were all deeply moving.

The powerful connection of Palestinians to their land became even more clear when I got to know and learn from the works of some of the great Palestinian poets such as Tawfiq Ziad and Mahmoud Darwish or the Palestinian artists like Ismail Shammout and Kamal Boullata. The images they created and the feelings they evoked have inspired generations.

You can often learn more about a people through the songs they sing, the stories they tell, or the art they love than you can from the political speeches of their leaders. In all of these forms of Palestinian popular culture, attachment to land looms large.

Palestinian refugees will recall their ancestral homes. Those whose lands have been confiscated by the Israelis will recall the simplicity of their village lives. The land that they nourished was where their histories are buried under the Earth waiting for a new spring in which to be born again. In short, their past lives, their present sorrows, and their hopes for the future are bound up in their attachment to their land.

Given this, it should be no surprise that Land Day (or Day in Defence of the Land) has become so important to Palestinians worldwide.

The history of this day is significant. The first Land Day was called in 1976 in response to the Israeli government’s plans to seize control of large areas of the Galilee region in order to expand the area’s Jewish population. Such seizures of Arab-owned lands to make way for Jewish immigration had been Israel’s modus operandi from the beginning of the state.

In the three decades before 1976, Israel had laid the foundation for their fledgling “Jewish state” by confiscating one and a half million acres of Arab-owned land and demolishing about 500 Palestinian villages – from which most of the Arab inhabitants had been expelled during the 1948 Nakba.

During those same three decades, the Palestinian citizens of Israel faced other significant hardships. They had emerged from the 1948 war shell-shocked from the horrors of the Nakba during which so many members of their families were forced to flee, so many others died, and much of their land, homes and businesses had been seized.

After the war, these Palestinians were subjected to restrictive Emergency Defence Laws under which the Israeli government imposed curfews, collective punishment, detention without charge and expulsion. Though nominally citizens of Israel, these Palestinians were, in reality, living under occupation in their own country.

It’s important to note that after the 1967 war, Israel applied these very same Emergency Defence Laws to the newly occupied territories.

Despite the hardships imposed upon them, the Palestinian citizens of Israel grew in confidence, political capacity and attachment to their Arab and Palestinian identity. They joined the Israeli political parties that would include them. They ran for, and won, elective office in the Arab towns and villages, and they organised in their own self-defence.

And so, when, in 1976, the government announced plans to issue new land expropriation orders in an effort to “Judaise” the Galilee, it was the proverbial “straw that broke the camel’s back”. They reacted by planning a huge nationwide general strike and protest march that would say “Enough!”.

Since the Israeli government was terrified of all forms of Arab resistance, it declared the protests to be illegal. Nevertheless, tens of thousands went on strike and peacefully marched. The day was marred by Israel’s violent response in which six Palestinian citizens were killed and more than a hundred wounded. This provoked outrage not only throughout the Palestinian community in Israel, but also among Palestinians in the 1967 occupied territories and those in the diaspora.

Every year since 1976, these March 30 Land Day protests have not only continued, but also spread throughout all of Palestine and in communities around the globe. They are a tribute to the continued Palestinian attachment to their land, their resilience, and their determination to rebuild their national community.

This year, Palestine’s Land Day fell on the Saturday between the Christian holy days of Good Friday and Easter Sunday. The convergence of these three days serves as a reminder of the ways in which the themes that they evoke have been essential components of the Palestinian national identity: attachment to their land, steadfastness despite losses endured, and belief in the promise of renewal.