Here are two little bits of Mike Tyson flotsam, you might call it, from the vast messy ocean of his personality.

In 2005, he flew into Washington DC with trainer Jeff Fenech for his last fight, with Kevin McBride. The pair were flying first class, seated at the very front of the plane. Fenech sat down and began reading.

After a few minutes, Fenech looked up to see a little boy sitting with him. When Fenech asked where Tyson was, the boy told him that he had never flown first class before, so Tyson had given him the seat and moved back to economy himself.

Conversely, here is a sample of Tyson addressing what he aims to accomplish when he is throwing a punch at an opponent: "I try to catch them right on the tip of his nose, because I try to punch the bone into the brain."

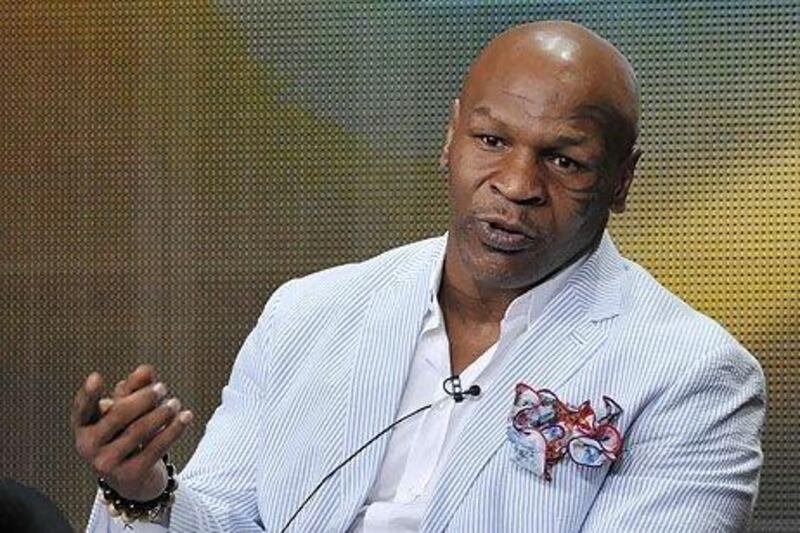

This weekend, as Tyson claimed that alcoholism and drug abuse brought him to the verge of death, it was natural to be reminded of these two snippets of his public life. Because it is in the very dissonance that lies the definition of Tyson the lisping, almost dandyish brute; the hyper-articulate self-assessor and ear-biter; the lover of pigeons, and unforgivably, a convicted rapist.

As he spoke Saturday and said that he was close to death, he looked and sounded like a man on the verge of professional comeback, or at least a man talking about a cameo role in a new film.

That effect has always been both the scariest and most-endearing thing about Tyson. Somehow, atop this muscled box of a body (author Ted Kluck once guessed that the distance between Tyson's shoulder and elbow was no more than six inches) sits a visage by turns boyish and brutish.

Then he speaks in that high-pitched voice and says, off the cuff, painfully eloquent things, such as, "I'm negative and I'm dark ... And I wanna do bad stuff. I wanna hang out in this neighbourhood alone [pointing to his head].

"That's dangerous to hang out in this neighbourhood alone up here, right? It wants to kill everything. It wants to kill me, too."

You are left wondering again at just what a specimen Tyson is. Most men that complex would long ago have allowed their contradictions to eat away at them like piranhas, until nothing was left. But not only is Tyson still around, he remains fascinating.

It is not because of the tragi-drama that permanently shadows him (I had forgotten, for instance, of the tragic death of his four-year-old daughter) and shapes his life. Instead, it is the residue from his spectacular impact in the ring in his earliest years.

Boxing is an inscrutable sport, which is where its likeness to chess is most evident. It is almost impossible for any but the most dedicated watchers and practitioners to catch the nuances and rhythms of fights, especially heavyweight fights, which can often seem slow and ponderous.

So the sport's following can feel faddish in that boxing has always been a cool sport to pretend to love and be knowledgeable about. The nature of it and the circumstances of where boxers come from often makes them more compelling than the average athlete, and they have also benefited from a degree of intellectualisation that writers such as George Plimpton and Norman Mailer have layered them with.

But when Tyson arrived, he stripped the entire edifice of this sport right down to what it was really about. This was not a sweet science, nor was it a noble art. This was about the uncomfortable thrill and power that chaos generates.

Tyson came to the ring to knock men out, not to wear them down gradually over 10 rounds with methods so refined and subtle nobody really understood it.

But anyone could tune in to a Tyson fight and be blown away by what he was doing, because everyone, even if they had not felt it, could comprehend the power of a punch that knocks you cold.

It was why, for instance, Tyson's team taped his earliest, non-televised fights. They wanted to capture his essence and spread it around the circuit, because they knew back then, as we know now, that it was impossible to experience him and come away unaffected.

Follow us

[ @SprtNationalUAE ]