January 16 marks 45 years since the departure from Iran of its last shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, marking the end of five decades of family rule and 2,500 years of monarchy.

“I am very tired,” a tearful Pahlavi said as he boarded an Egypt-bound flight from Tehran with his wife, Empress Farah.

In Tehran that day, hundreds of thousands of car horns blared in “wild scenes of celebration” as his departure was announced on the radio, with crowds celebrating across the country as newspapers reported “frenzied rejoicing” in the capital.

In Paris, soon-to-be leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, exiled by the shah in 1965, congratulated Iran on the “first step towards victory”.

Less than two weeks later, he would return to Tehran, welcomed by crowds of up to five million people before being declared Iran's first supreme leader.

The royal family re-emerged in 2022 as the fiercest anti-government protests yet broke out across Iran following the death of Mahsa Amini in the custody of the morality police after refusing to cover her head.

The protests spread to every province and attracted support from around the world, as crowds in North America and Europe denounced Tehran and its paramilitary forces responsible for the heavy-handed response.

Iran's diaspora led calls for tougher action against Iran. Among voices critical of the government was Reza Pahlavi, the shah's son and exiled prince, whose supporters believe he is the legitimate ruler of Iran.

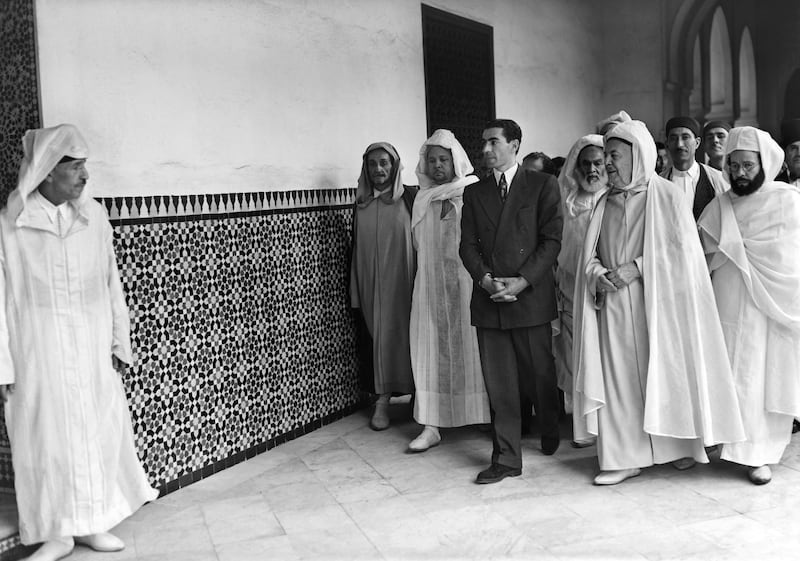

The Pahlavi dynasty left a complicated legacy.

While it ushered in unprecedented economic reforms, privatised oil wealth and increased rights for women, many remember the shah, who died of cancer in Egypt in 1980, as an autocratic ruler reliant on his secret police, corruption, and political repression.

Fierce disagreement over his legacy as ruler has splintered opposition to the government in Tehran.

Disconnected from the people

“Eventually, we went faster than some people could digest,” Pahlavi told the Washington Post from Cairo in the months before his death, defending his rule as a “blossoming” of wealth and intellectual life.

The most emblematic policy of his reign, according to Dr Sanam Vakhil, was introduced with the 1963 White Revolution, when land was distributed to millions of people and increased emphasis on literacy and education, “the development of healthcare, infrastructure … policies aimed at economic development”.

But his critics also point to widespread repression and a leader out of touch with the needs of his people.

“He wasn’t the most connected individual with his people,” Dr Vakhil, director of the Middle East and North Africa programme at Chatham House, a UK think tank with ties to the British government, told The National.

“The [1979 Islamic] Revolution didn’t come out of nowhere. People were seeing grievances and becoming politicised.”

Anger at the shah reached a peak in 1978, when anti-government protesters across the country were killed, including student demonstrators in the holy city of Qom.

The city had been the seat of Khomeini's political power before his exile in France.

Protesters who rallied against what many described as state terrorism under supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in 2022 drew parallels with the public anger after the Cinema Rex fire in Abadan in August 1978.

There, four men, suspected of being religious radicals, burnt more than 400 people to death after locking them in the building.

The attack has been blamed on secret police as well as revolutionary Shiite militants, who had a track record of burning cinemas. It nonetheless politicised many people and led to a wave of anger against the shah.

Like the Iranian regime today, Pahlavi sought to make his country a regional heavyweight, but notably kept economic and consular relations with Israel, which was reliant on Iranian gas.

Reza Pahlavi made a landmark visit to Israel in April 2023, positioning himself as a community figurehead by “delivering a message of friendship from the Iranian people”.

“Mohammad Reza was contending with a lot of regional competition, the impact of communism, the Cold War and trying to build greater domestic legitimacy for his role,” said Dr Vakhil.

“His father [Reza Shah] was not particularly well-loved domestically … and so his policies and politics were driven to strengthening the monarchy.”

That involved the imprisonment of political opposition, and opponents of the monarchy and the repression of minorities, including groups that have long suffered under the current theocracy.

In 1934, schools for followers of the Baha'i faith were shut upon orders of his Reza Shah. Minorities such as the Baha'i were often used as scapegoats by the shah for unpopular government policies, according to community campaigners.

The shah’s secret police were one of the “main agencies” of persecution” against the minority, the Baha’i said.

Memories of this resurfaced during the Amini protests, when there was an outcry after the former deputy head of Savak, Pahlavi's secret police force, was pictured at a pro-democracy for Iran rally in the US in February 2023.

“In a free Iran, he would be put on trial,” one X user wrote.

“Ordinary Iranians were marginalised, they weren’t a key pillar of the government’s focus at the time,” said Dr Vakhil.

Today, Iranians who seek an end to the regime in Iran are not looking to opposition figures abroad, whose influence has waned since the protests triggered by Ms Amini’s death.

“There’s been an awakening where no one from abroad is going to be able to swan in and save Iranians from their own leadership,” said Dr Vakhil.