One hundred years ago, Britain's foreign minister, Lord Arthur Balfour, wrote a brief missive to Lord Rothschild, the unofficial head of British Jewry, promising Britain's backing for a national homeland for Jews in Palestine – a promise, 67 words in length, which has (mis)shaped the Middle East along profound fault lines ever since.

The Balfour Declaration, as it is known, also noted that nothing would be done “which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine”.

The fact that it doesn’t expressly identify those “non-Jewish communities” as “Palestinian” or “Arab” says all that needs to be said about Balfour’s contemptuous disregard of the indigenous population, many assert, turning to history to prove their point.

This legacy of British colonial imperialism and Israel's ongoing "colonisation" Palestine are among the unaddressed realities of Balfour's declaration by the current British government. But what about those Palestinians and British-Palestinians living in the UK today – how do they feel about their adopted homeland and its role over the past century in their dispossession?

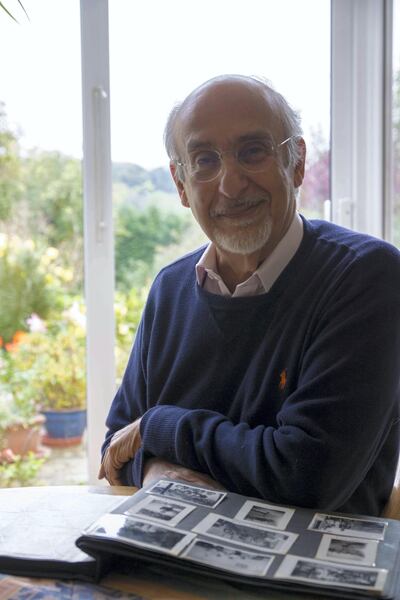

Taysir Dabbagh, 79

Taysir Dabbagh was 10 years old, living with his family in Jaffa when, in April 1948, his life was nearly tragically ended in a terrorist attack by Zionist militants.

Now aged 79, in his home in High Wycombe, a town west of London, Taysir thumbs through an old notebook, a diary his eldest brother, Hassan, kept in the days leading up to the Nakba – when more than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled from their homes, during the Palestine War.

In neat handwriting, Hassan chronicled the day his youngest brother was nearly murdered. Taysir reads a few entries in Arabic then recalls the incident. “I was walking home after trying to buy some coffee for my mother, and three other children were coming from their homes to visit their relatives who lived in the same alley as us.

“On one side is the hill there’s a cemetery at the top overlooking the houses and the sea. As we approached each other, this grenade exploded right among us. I was wounded in several places: my tummy, my shoulders and my head.”

He pauses for a moment as tears well up and his voice breaks, then he apologises: “Sorry, it is very emotional for me. Whoever hurled that grenade saw that we were only children. This is al-Ajami, the quietest place in Jaffa. They knew that if you terrify these people by attacking their children, it will cause a great upheaval. And that’s what happened.”

For Taysir and his family, Britain’s promise of a Jewish homeland inside Palestine gave birth to modern terrorism.

Days later, his family fled Palestine by lorry, and Taysir witnessed his last glimpse of home from a stretcher. Weeks later, they arrived in Damascus, his home until he was 20, after which, longing for “enlightenment” – he says with a laugh – he followed his older brother and moved to England.

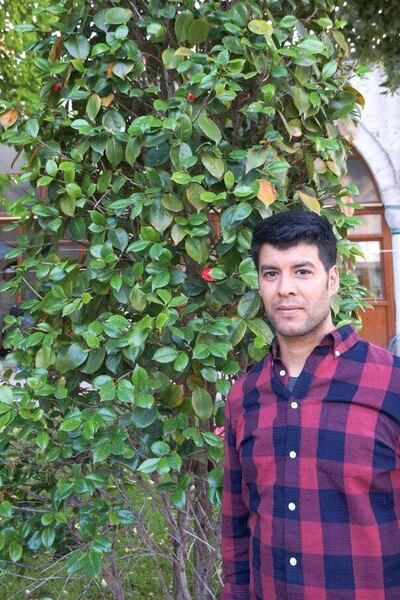

Omar Qattan, 53

For another generation of Palestinians living today in Britain, like Omar Qattan, chairman of the A M Qattan Foundation, a leading Palestinian arts and education organisation, the Nakba had displaced the family by the time he was born. The youngest of four, from a highly political family, Omar grew up in Beirut, where his Palestinian identity was hard to elude at the time.

“Being in Beirut was particularly powerful in terms of the Palestinian identity issue because this is where it was flourishing. It was being projected and spread through writing and folklore – it was everywhere, and it was embraced by so many Arabs. And, of course, the revolution was very much at the centre of everything, both positively and tragically. Some of my childhood memories include [author and PLO member Ghassan] Kanafani’s assassination, and then later Kamal Nasser and two Fatah leaders – Mohammed Yousef al Najjar and Kamal Adwan – these were very lively and moving incidents in my memory as a child.”

In response to these rising tensions between the Lebanese right and Palestinian nationalist forces, his parents sent their children abroad to study in 1975. Omar attended a boarding school in Somerset and, a few years later, read literature at the University of Oxford.

His sense of identity underwent several phases, at times simply wanting to be “an English boy”, free to immerse himself in his new culture; but the tragic events engulfing the Palestinian community in Lebanon, culminating in the massacre at Sabra and Shatilla camp in 1982, would always compel him to identify strongly with his roots.

He was one of three students who initially comprised the Palestine Society at Oxford and it proved the start of a journey into his Palestinian identity.

“I met a film-maker named Michel Khlifi, at the time a young Palestinian film-maker. He came at the invitation of our little Palestine Society to show his first film at Oxford. I had never actually seen historic Palestine. All we had seen were revolutionary films made by the PLO, usually in Lebanon, so this was a real revelation and it made me fall in love with the people. It was a renewal. Or maybe the first time I could connect so visually and directly,” says Omar.

For many British-Palestinians born in Britain, their sense of identity and activism are often a result of the stories they heard from relatives who lived through the tragedy of the Nakba: the heart-breaking accounts of dispossession, humiliation, deaths, and the faded land deeds and keys to ancestral homes they hold on to.

Tamara Ben-Halim, 32

A young Palestinian rights advocate, born in London to parents with strong roots in Palestine, Tamara Ben-Halim grew up in Saudi Arabia. She lived there until she was 10 years old, and that was when the family moved back to the UK.

She says the community she lived in while in Saudi Arabia was predominantly Palestinian, and the food eaten, dialect spoken and clothes worn – by the women at least – all strongly reflected this.

But the most profound, indelible impressions of Palestine Tamara experienced were when she was a young girl.

“I grew up with my grandmother telling me about her happy childhood memories of growing up in Jaffa,” she says, “with the orange groves nearby, the sea and everything; as well as that most present and tragic memory of having to leave when Zionist forces began bombing the town; of her father telling her and her sisters to pack their bags, saying that they’d be back in a week, then leaving for Egypt and never returning. That trauma is something that stayed with her and which she told me about many, many times, and it really affected me. It is a big factor in terms of the connection I have to Palestine today.”

That identity for Tamara has manifested itself in recent years primarily through a “career trajectory that has gradually and organically shifted towards focusing on the Palestine issue, moving from charity and humanitarian work, to documentaries, to human rights work”.

London is where she feels at home, but Palestine is also where her heart is.

But it isn’t just Britain’s colonial legacy that is an issue. Israel’s wars and its systematic discriminatory laws that dictate the lives of the nearly five million Palestinians living under Israeli occupation, often depend in part on tacit or vocal support from the British government of the day. Many Palestinians affected by Israeli violence and other manifestations of injustice have ended up adopting Britain as their home.

Atef al Sha’er, 35

A soft-spoken and articulate poet and lecturer in English at London’s Westminster University, Atef al Sha’er is from Rafah, Gaza. In 1999, he left Gaza to study English literature at Birzeit University in the West Bank. He was then offered a chance to be “smuggled” out of Palestine to continue his studies abroad. He acted upon the opportunity.

That freedom, however, came at a cost he didn’t fully envisage at the time – because he left unofficially, he is unable to return to Gaza without risking imprisonment by the Israeli authorities. He has thus missed out on nearly two decades of family life, including his father’s funeral several years ago. For him, the opportunity was an extremely bittersweet one.

“One aspect that became clear with time – which now I think is sad – is that I am here in Britain with a British passport and I can visit anywhere I like pretty much. And I haven’t stopped travelling over the past few years – that is,

except to my home, to my country, which is maddening.

“Last year I was in Jordan and this year I was in Egypt. I felt it profoundly, that I was so close to home, but I was not able to go home. It felt very disturbing and strange,” he says.

Balfour’s words would eventually lead to the creation of a Jewish nation at the expense of another. One people, with a long history of exile and persecution, would create new exiles, many of whom continue to be persecuted at home and in the diaspora for being Palestinian. Living in Britain, how necessary and important – and indeed possible – is it to retain one’s Palestinian identity? And is it a betrayal to regard your one-time coloniser’s home as your own?

“I don’t see this as an identity issue,” says Omar. “I never have, apart from briefly feeling alienated from my Arab roots. I’ve always dealt with Palestine as an ethical and political issue – I find that question of identity pretty sterile and reductive.”

Atef takes a similar stance.“I’m an Arab and, of course, I come from this background. But I also have other baggage which is quite strong, which is European baggage, and I am allowed to be both here and in Europe, and it’s easy: it doesn’t feel laboured, I don’t have to justify myself – this is who I am and that’s OK.

“Whereas if I went back [to Palestine] my life would have to be circumscribed and ruled by particular habits and conditions and customs, which aren’t bad in themselves – but my life conditions and my history have made me evolve, move away from this, or transcend this. It’s just the way life moves on.”

In the lead up to the marking of the centenary British prime minister Theresa May said unequivocally there would be no apology regarding the Balfour Declaration on November 2 when the centenary was marked, insisting Britain is “proud” of its support in helping to lay the foundations for the birth of Israel.

To those interviewed for this piece, this is a moral and legal disgrace. Omar insists “the solution can only happen in the legal sphere, and that is through recognition first of all, and proper compensation, both material and, more importantly, political”.

Centenaries come and go. But the struggle for justice will continue for Britain’s Palestinian community and its supporters. That grassroots movement is growing in strength and numbers and is showing the government to be out of touch in a way redolent of South Africa anti-apartheid movements several decades ago.

Taysir, Omar, Atef and Tamara each represent different generations of Palestinians who have made Britain their home. Each continues to promote the Palestinian narrative in their own personal and professional capacities through culture and education. It’s change from within and it’s making a difference.

“We are much stronger and much more able to muster solidarity and support when we deal with Palestine as an issue of justice and equal rights,” says Omar, “not a competition over identities.”

__________________

Read more:

[ Contrary to popular belief, the Balfour Declaration did not sanction the existence of Israel ]

[ Balfour Declaration: how Britain broke its feeble promise to Palestinians ]

[ Banksy holds 'apologetic street party' for Balfour outside his hotel overlooking Bethlehem wall ]

__________________