They are, in the words of Google, the "fun, surprising and… spontaneous" changes to the company's search-page logo that celebrate holidays, anniversaries and the lives of artists, pioneers and scientists "and bring smiles to the faces of Google users around the world".

“Over the years, Doodles have become one of the most loved things we do at Google and more so in the Arab World,” says Tarek Abdalla, head of marketing for Google Middle East and North Africa (Mena), based in Dubai Internet City since 2008. “Our users look forward to going to our homepage and seeing what or whom we are celebrating.”

The purpose of Doodles, he says, is “to delight and inform our users around the world as, ultimately, Google Search is about discovery, learning something new about the world, having fun and getting inspired”.

But when you’re dealing with a search portal that handles in excess of 3.5 billion global requests every day, and 1.2 trillion in a year, no message it conveys, however innocently, can be dismissed purely as a bit of “fun”.

In 2004, after Google announced ambitious plans to create a virtual library by digitising books from major university collections in the United States and the United Kingdom, the French government protested against what it saw as blatant cultural imperialism.

Writing in Le Monde, Jean-Noël Jeanneney, head of the French National Library, condemned the plan as a "confirmation of the risk of crushing American domination in the way future generations perceive the world".

Set against the feared primacy given to Anglo-Saxon culture by the great Google Books project, it is easy to dismiss each individual Doodle as nothing more than a harmless bit of fun. But when seen as a whole it becomes clear that in its own way the Doodle programme operates as a subtle but highly effective form of cultural imperialism.

The first Google Doodle, drawn to celebrate the United States’ Independence Day, was published on July 4, 2000. Since then more than 2,000 have been designed for Google’s national homepages worldwide – more than 360 so far this year alone.

Googlers using the UAE homepage have seen 83 Doodles since the first – which celebrated the Persian new year – appeared on March 20, 2004, and UAE National Day has been marked every December 2nd since 2008.

Doodles can be targeted at single nations, groups of nations or the entire world – and even individuals; sign up to Google and on your birthday you will receive your very own “personalised” Doodle.

The company says ideas for Doodles are generated both internally and by users – suggestions can be submitted to proposals@google.com – and each one is produced by a dedicated team of illustrators (aka, doodlers) and engineers based in the US. But what’s less clear is how Google decides which countries receive which Doodles.

What do Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist Max Planck, mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler, author Charlotte Brontë, and engineer and inventor Hertha Marks Ayrton all have in common with the UAE? Absolutely nothing, beyond the fact that all four have been celebrated in Doodles published on Google’s UAE homepage, in the process raising the intriguing possibility that the US-based global company whose motto is “Do the right thing” may unwittingly be doing something rather wrong indeed, by peddling western culture at the expense of all others.

Consider one of the most recent Doodles to pop up on Google's UAE homepage, which on December 10 celebrated the achievements of Robert Koch, a German doctor who in 1905 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on tuberculosis.

The Doodle also cropped up on Google homepages in the US, Canada, Russia, Australia, Iceland, Germany, India, Japan and four countries in South America.

Clicking on that Doodle will doubtless have been an education for many in those countries, including the UAE, who had never heard of the good doctor or his work. So far, so good. Shared knowledge – “learning something new about the world”, in Google’s words – can surely serve only to unite disparate communities and inspire individuals to look beyond their own borders, both national and personal.

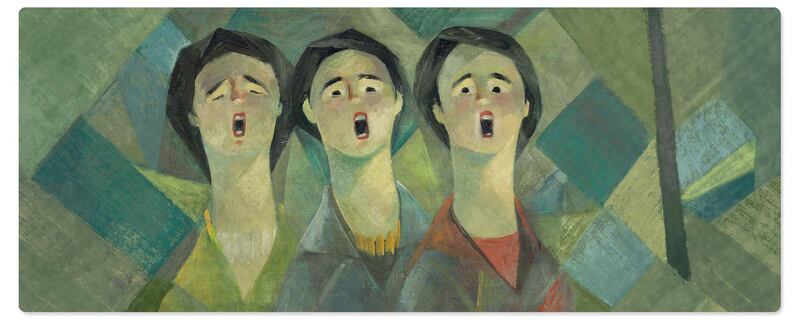

But rewind to June 30 of this year and the Doodle marking the 81st birthday of the Algerian novelist and filmmaker Assia Djebar, who was only the fifth woman (and the first writer from the Maghreb) to be elected to the Académie Française.

Her work sought to alter the perception of women in the Muslim world, and in 1996 earned her the prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature. If widely disseminated, the story of such a pioneer would surely have contributed to a balancing of the perception in the West of the Islamic world. Unfortunately, however, no-one beyond the borders of the UAE and 10 other Mena countries saw her Doodle.

And there are many such examples of one-way cultural dissemination. In May 2011, an animated Doodle marking the 117th birthday of Martha Graham, an American choreographer who died in 1991, was shared with almost the entire Googleverse.

Again, broadening knowledge can only be a good thing (although to some in the Middle East, unfamiliar with Graham’s oeuvre, part of the animated sequence celebrating several of her dances appeared controversially to be an exhortation to Muslim women to cast off the veil). Yet time and again Google fails to reciprocate by sharing the cultural highlights and achievements of the Mena region with the wider world.

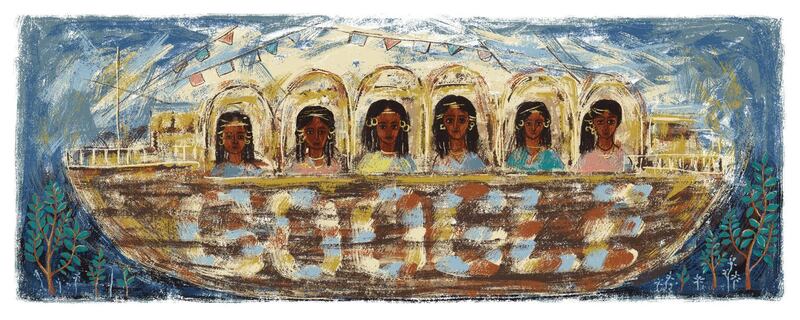

Take the celebration in 2012 of the birthday of Muhammad Ibn Battuta, the 14th-century Moroccan-born scholar and explorer whose account of his extensive travels remains an invaluable record of life throughout the Middle East and Asia in the Middle Ages.

It would, perhaps, have done little harm for the wider world to learn of this pioneering Muslim’s exploits on the occasion of his 708th birthday on February 25, but the Doodle commemorating this was once again limited to the UAE and 10 other Mena nations.

Time and again, US-based Google shares the trivia of Americana with the world like a proud parent Tweeting images of little Johnny’s latest amazing pre-school daub.

On September 24, 2011, the Doodle marking the 75th birthday of Muppet Show creator Jim Henson popped up on every single homepage globally, including that of the UAE, as did the April 3 anniversary of the ice cream sundae, which was invented in the US. Yet very few people, discoveries or anniversaries of note from the Middle East have ever made it very far out of Google’s Mena ghetto.

Two Doodles in particular illustrate this disparity with perfect asymmetry. On July 24, 2012, the entire world, including the UAE, was invited to celebrate the 115th birthday of American aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart, who disappeared flying over the Pacific in 1937. On October 29, 2014, only Mena countries received the Doodle marking the 107th birthday of Lotfia El Nadi, the Arab world’s first female pilot, campaigner for women’s equality and the first woman after Earhart to fly solo.

What is the true purpose of the Doodle then? If it is a cynical exercise in generating vast amounts of publicity for Google, then it is a tremendous success – around the world newspapers never tire of reporting the latest local Doodle celebrating some aspect of local culture. But if the point is to make Google users around the world feel they are part of a vast, global community, then this is something of an exercise in self-deception.

Yes, all seven UAE national days have been marked since 2008, but these Doodles are seen only in the UAE. Likewise, the Doodle on November 28, 2013, celebrating Dubai’s successful bid to host Expo 2020 was for UAE eyes only.

This is particularly strange given that, in the words of the Bureau International Expositions, the intergovernmental organisation responsible for Expos, this is “the world’s largest meeting place… a global event that aims at educating the public, promoting progress and fostering co-operation”. But not, apparently, in Doodleland.

Is Google aware that its Doodle programme is weighted heavily in favour of western culture at the expense of the rest of the world, and that it is missing an opportunity to use the power of its vast and virtually monopolistic reach to mitigate against the prevailing sense of the “other” that is so corrosive in international relations?

Maybe, but Google isn’t saying. It declined to put up anyone for an interview or to issue a statement in response to the specific issues raised in this article. However, it did offer a background briefing in which it identified three recent Mena-specific Doodles which, it claimed, had been published globally. In fact, although all three did receive some exposure beyond the Mena region, none could be said to have run globally.

The 90th birthday on November 10 of the Lebanese singer Sabah was celebrated outside Mena in just seven countries – Cuba, Iceland, Sweden, Belarus, Croatia, Australia and New Zealand.

An animated Doodle marking the 117th birthday on March 23 of the Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy did a little better, running in an equally eclectic group of 12 countries: Cuba, Peru, Argentina, Chile, Iceland, Ireland, Sweden, Belarus, Serbia, Greece, South Korea and Japan.

But neither saw the light of day in the US or most of Europe. The Doodle on May 31 this year, celebrating the life of the architect Zaha Hadid, who died in 2016, did best of all. It reached 28 non-Mena countries, including the US, Canada, Russia and the UK (but excluding most of Europe, Africa and Asia).

But although she was born in Baghdad, Hadid was educated in Britain, where she moved permanently in 1972, subsequently adopting British citizenship.

Hadid’s many projects around the world included Abu Dhabi’s striking Sheikh Zayed Bridge, which opened in 2010.

“Fun and surprising” Google’s little drawings might be. But the real surprise is that far from uniting peoples of the world by building two-way cultural bridges, the Google Doodle is in the serious business of perpetuating the cultural hegemony of the West.

________________

Read more:

[ What the UAE Googled in 2017 - in pictures ]

[ Google reveals UAE's most popular travel search queries ]

[ Social media beyond the grave ]

________________