The old Mercedes is that dusty shade of tan that you never see anymore, but which seemed almost inevitable a few decades ago. Rounding the bend, the well-preserved saloon crunches up a steep, tree-lined driveway, chrome shining in the California sun. As the car pulls near, a familiar but unexpected odour emanates from its exhaust pipe: french fries.

The driver, a shaggy, bearded man in his early thirties, is Zachary Miller, and his 1982 Mercedes 300D is fuelled with B99, biodiesel fuel made from 99 per cent waste vegetable oil (WVO) - the sickly, brown sludge found in the deep fryer at your local chip shop, albeit well past its useful kitchen lifespan. It has a long history of reuse, turning up in a variety of products including pet food, soap, clothing and, most distressingly, cosmetic products. And while using it for fuel isn't entirely new - Rudolf Diesel initially ran his eponymous invention on peanut oil - an enterprising community of alternative-fuel enthusiasts have repopulated the meandering road between vegetable oil and the combustion engine.

There are a few complications, of course, particularly since no production vehicle is currently designed to run on B99. Then there's also the nagging issue of procurement; while a certain segment of his peers scrounge WVO from sundry Chinese restaurants and doughnut shops, Miller opts for a more conventional approach. "I buy my fuel at Biofuel Oasis in Berkeley," he says, referring to a local biofuel station. "The car gets over 300 miles to a tank, so most of the time I can refuel at the same location."

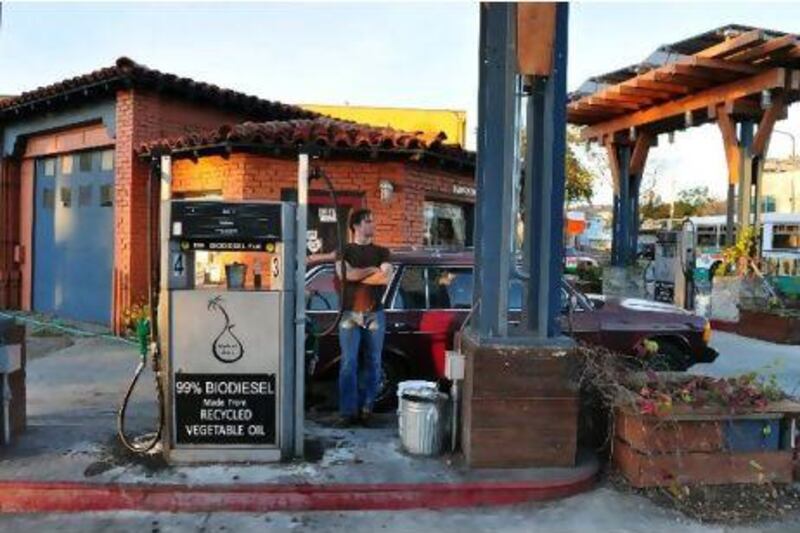

Biofuel Oasis looks like a downmarket petrol station in a somewhat marginal neighbourhood. The car park is stained and cracked, weeds poke out at various intervals and a homeless man slumbers on a mattress laid out next to the entrance to the toilet. Inside the retail space, which doubles as an urban farming supply shop, the atmosphere is very different. Over the phone, author and Biofuel Oasis co-founder Novella Carpenter prepares me for the shop's unexpected confluence of interests: "I think of it as a sort of country store, in an urban setting," she says. "People hang out, share knowledge and ideas; it's become a sort of community hub." This pairing of urban farming and biofuels is perhaps more relatable in context. Carpenter is the author of a book entitled Farm City: The Education of an Urban Farmer.

Without the support of the larger automotive industry, biodiesel consumers are left with small businesses and their fellow enthusiasts to provide the sort of troubleshooting and information you might otherwise expect from a dealership. The internet, as always, is full of opinions on the subject, but having a local community with a shared interest is ultimately more powerful, and explains why Berkeley has become a B99 capital. Information is distilled and disseminated through small enterprises like Biofuel Oasis, where experienced users such as co-founder Amy "Ace" Anderson can give you a thumbnail sketch of how to process your own WVO for use in a diesel engine: "It's pretty easy," Ace says optimistically. "The veggie oil molecule is essentially glycerine attached to free fatty acids.

"To make biodiesel, you use a chemical process to break the molecule down, separating out the glycerine as a waste product - it can be composted or used to make soap. You're then left with these free fatty acid strands that you combine with alcohol, either methanol or ethanol, which hooks on to the fatty acids to make a biodiesel molecule, or methyl ester." Right, but how exactly does one achieve this? "It's fairly simple," she begins, still confident that I'm following the chemistry tutorial. "There's some heat involved in the process, as well as a catalyst. You can build your own processor out of a hot water heater, some tubing and a couple pumps." Simple, it would seem, is a relative term. And while intrepid souls like Ace are processing their own WVO, Carpenter assures me that the majority of biodiesel consumers buy retail.

Miller is one of those consumers. When he's not close enough to fill up at the Oasis, he can navigate his way to one of a handful of other B99 stations in the state, or simply refill with conventional diesel or more commonly available iterations of biodiesel; B2, B5 and B20, which use 98, 95 and 80 per cent petroleum-based diesel respectively.

To run biodiesel, the fuel lines in the 300D needed to be replaced, since the conventional hoses don't stand up well to the alternative fuel. Miller didn't have to modify this car himself though; biodiesel supporter and US congressman Dennis Kucinich used this particular 300D during his 2004 bid for president. Sadly, not long after my initial interview with Miller, the emergency brake on his Mercedes failed atop a different, but equally steep hill. The car rolled for about half a kilometre unobstructed, building up speed until it ploughed headfirst into a bank building. Undaunted by this setback, Miller soon after replaced the write-off with another Mercedes 300D, a model that, due to price and reliability (emergency brake failures aside) is perhaps the most popular platform for running B99.

A brief, highly unscientific survey conducted at Biofuels Oasis one afternoon confirms this bias, as a steady stream of 300D saloons and estates pass through, punctuated by the odd Japanese or American diesel. Newer diesel cars, particularly Volkswagens, show up as well, although perhaps at greater jeopardy. "We ran commercial biodiesel for a few years in our 2003 TDI Jetta Estate," says Eric Backman, a customer at the shop. But when the fuel pump failed, the expense of replacing it, combined with the mechanic's caution against using biodiesel in that car were enough for Backman and his wife, Kelin, to swear the stuff off. "Repair bills like that cut down on the economic efficiency of running an alternative fuel," offers Kelin. "When you look at conventional diesel, we're still benefiting from greater efficiency than offered by the same car with a petrol-based engine. Ultimately, that was enough for us."

But while diesel offers improved fuel efficiency over petrol, it still produces pollution. Biodiesel offers a considerable improvement. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, biodiesel reduces emissions of carbon monoxide by 48 per cent, carbon dioxide by 78 per cent and particulate matter by 47 per cent compared with conventional diesel fuel. Conversely, the Backman family's TDI gets as much as 5.2L/100km on the open road running diesel, while a 1980s 300D is roughly half as fuel efficient running biodiesel.

The United States produces somewhere around 11 billion litres of WVO each year, largely through commercial food production. If - and this is a very large "if" - every litre were used for biodiesel production it would, at most, offset just less than one per cent of US petroleum consumption.

Along with restaurants, a largely untapped source for WVO flows beneath cities all over the globe in their sewers, where a certain portion of it winds up every time you wash a frying pan. Alicia Chakrabarti, an engineer with Berkeley's East Bay Municipality District (EBMUD), ran a six-month pilot programme that filtered oil out of waste water, processed it into biodiesel and used it to power four of EBMUD's service vehicles with an eye towards potentially fuelling their fleet. "We ran the trucks on 100 per cent biodiesel as well as different blends," explains Chakrabarti. "Ultimately, what matters to us is which blend performs the best in the trucks, with the least amount of maintenance. Since you're not likely to have enough waste oil to use biodiesel exclusively, it's really about augmenting, not replacing conventional diesel."

Back at the Biofuel Oasis, Nathan Dalton's maroon 1985 Mercedes 300D bears the marks of decades of service, the last few years of which have subjected it to the rough treatment of his three small children. Dalton's mechanic, a fiery German émigré, assures him the old estate has plenty of kilometres left to go. "Your [six-year-old] son, he will drive this car one day." For Dalton, running biodiesel offers a way in which his activism and consumerism can align. "I feel really good not giving my money to big oil companies. That's the main reason I like using biodiesel."

Dalton describes Biofuel Oasis as "an incredible community of DIY types. I guess I could go there without a diesel car, but it wouldn't be the same. I also love the smell of biodiesel fumes coming off other cars that I pass by around town. I always feel a sense of kinship - like a little badge of affiliation in a club that not many know about."

The affiliation that Dalton refers to is something borne of commitment. Biodiesel users like Dalton and Miller are aligning personal spending with activism and their numbers, while small on a national scale, are growing. In 2003, at the launch party for Biofuel Oasis, Ace, Carpenter and their fellow founding partners hit on a way to, as Ace describes it, "sensationalise just how non-toxic B99 actually is". To make their point, the founders gathered on the stage and raised a toast to biodiesel, their shot glasses topped up with B99. WVO has many uses, but when the Biofuel Oasis team downed their own product, it may have been the first time a WVO by-product had been consumed as a beverage.

At current levels of consumption, B99 isn't curbing US demand for oil much, but it does show a groundswell of consumer interest in alternative fuels. The majority of B99 enthusiasts may not literally drink from the cup of biodiesel, but their figurative thirst for alternative knowledge is spreading.