In researching this feature, I tried to get the exact figure of active car manufacturers in the pre-war years; the Great War of course. In this context the usual “pre-war” connotation of World War II suggesting an automobile’s era, is much too late. In any case, I didn’t do a very good job of ascertaining an accurate figure. What I did find is the exact opposite: a lot of defunct brands. And it really is a lot.

Let’s put it this way: in 1914 alone, 115 car marques shut their doors. Granted, some of them had only just opened their doors the day before the Europeans started entrenching, but this number, 115 automobile manufacturers, is for US makes alone. Goodness knows how many European brands died as industry shifted to accommodate armies, and let’s not forget that America was, true to tradition, a bit late to help out in the Allied effort.

Among all these lost jobs however, unfulfilled dreams and forgotten cars, all this despair and death, was a beacon of light. A birth. Maserati.

The famous Italian race team and boutique car marque is 100 years old in 2014, although “boutique” hardly constitutes a massive 16,000 sales last year. By 2015 this will jump to 50,000, mostly thanks to the new Ghibli, but so far the charge has been led by the flagship sixth-generation Quattroporte saloon – a far cry from the second generation Quattroporte, of which Maserati produced 13 between 1976 and 1978.

Things clearly weren’t always rosy for this “other” Modenese car maker. It had almost as many hits as it had misses, more financial woes than I can count and a sad end to the brand’s racing exploits. Yet Maserati is still here today, which as we’ve seen is way more than can be said of hundreds of other dreamers in those pioneering days of four-wheeled transport.

The story begins in the late 19th century with an Italian railway worker named Rodolfo Maserati, a father of seven sons. Passion for engine design and engineering coursed through the household, but it was the most famous of the sons, Alfieri, who banded the rest of his brothers and helped make their family name illustrious around the world. Through all of Maserati’s (the company) hardships, one thing remained the same: a brotherly bond with Ferrari. Il Commendatore Enzo was always a Modenese neighbour and rival, a totalitarian with a disregard for his staff, customers and drivers. Infamously, if a Ferrari won a race, it was down to the car. If it lost, it was the driver.

But Maserati was always filled with company lifers, staff who grew up with the maker and remained there into retirement. There is a warmth to Maserati, a commoner’s quality, that underdog factor – despite the fact that Maserati was a racing giant in the pre-war (the proper pre-war) years and afterwards in the newly established Formula One class.

Rodolfo, an engine driver, must have been a huge inspiration to his sons who dreamt of attaining the speeds of Italy’s “iron steam horses”, without the steam of course, and off the rail tracks. Eldest son Carlo, for example, was winning races at 17 on a bicycle powered by an internal combustion engine of his own design. Immediately he was hired full-time by Fiat (then F.I.A.T., or Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino) as a test driver, which didn’t stop him from designing more engines in his spare time. While in Turin in 1900 he stuck one of his engines in a wooden car chassis, which could be loosely considered as the first Maserati ever.

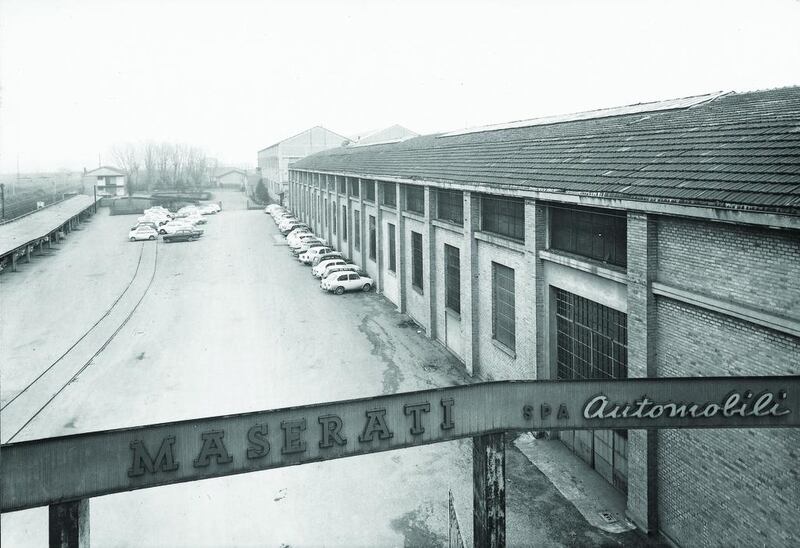

Moving to Isotta Fraschini, at the time one of the most prestigious car makes in the world, Carlo brought along his brother Alfieri, the 16-year-old youngster impressing not only with his testing and racing skills but also two other obvious family traits: engineering and design. Sadly, Carlo died young and the family name came to rest on Alfieri, who opened a service centre for Milanese Isotta Fraschini cars in Bologna. He was joined in the new business by his brothers. The Great War then called up some of the older brothers to Italy’s many fronts but in July 1914 came a milestone, in the form of a sign declaring, “Officine Alfieri Maserati SA”.

The brothers never saw any fighting; the army instead rightly recognising their talents and steered them towards aircraft engines. When peacetime came around, Alfieri commissioned his brother and artist Mario, the only one of the siblings without any engineering expertise, to design a logo fitting of the young company, and so was born the legendary Trident, inspired by the statue of Neptune in Bologna’s Piazza Maggiore.

Today the company considers a 1920 model to be the first real Maserati, but in fact it was an Isotta Fraschini chassis with a Hispano Suiza engine and a SCAT transmission, a real hack job made all the more difficult with the use of different still axles and wheels. But the hybrid won races, and after stints in oil changes, airplanes and spark plugs, motorsport became the company’s calling.

This success led to racing consultancy for Diatto. However, by 1925 the company couldn’t afford to keep racing. So with the help of a wealthy Marquis, friend and fan, Alfieri could afford to acquire 30 Diatto chassis and begin a production line of his own. And so, the Tipo 26, named for its year of manufacture and the first real, true Maserati – Trident and all. It was a 1,500cc racing thoroughbred, winning its class on its debut. This was to be a familiar sequence of events for the company well into the 1950s – build a car, win a race. And maybe sell something.

By 1929 Maseratis were breaking speed records with 16-cylinder engines. The following year brought the brothers their first international race victories, and a head-to-head with a certain Enzo for the first time. Then, Alfieri died.

Bindo Maserati took over and the company survived its first difficult financial situation, thanks in part to a new model dubbed Tipo V5. And just like that, total world domination, as legendary driver Tazio Nuvolari scuffled with Enzo, left Ferrari and joined Maserati to pilot the 8CM race car and win prestigious, top-tier Grands Prix all over Europe. A rivalry was born.

However, throughout the 1930s Maserati had bigger worries; bigger even than the Prancing Horses rolling through its Modenese neighbour’s gates. The Third Reich put huge backing behind Mercedes and Auto Union (better known today as Audi) to demonstrate Germany’s engineering might on the track, so the Maserati brothers were forced to fight back and get as much ammunition as possible, in the form of financial clout. The brothers sold the company to Italian entrepreneur Adolfo Orsi, and the first “financial era” began; the Orsi era.

Orsi didn’t stick his nose into any technical issues because innovation and engineering were the brothers’ forte. Everything worked well, but little did the Maseratis know what other eras awaited them. In fact they worked so well that the ageing 8C won the legendary Indianapolis 500 in 1939, Maserati becoming the only Italian maker to ever achieve such a feat. Twice.

Another world war put a stop to serial production but, when racing resumed, none other than the great Juan-Manuel Fangio was drawn to the Trident alongside other team drivers like Louis Chiron and Prince Bira. Maseratis kept on winning races and championships, and irritating Enzo Ferrari.

During the 1960s, Maserati’s efforts shifted hugely from racing to prestigious road car manufacture, which attracted such clientele as the Shah of Iran. And even though the company moved away from the racetrack, there was still enough time and effort available to create such bolides as the iconic Birdcage, a racer that decimated competition in the hands of privateers all over Europe and the United States.

Still, focus was definitely on road-going machines, and the 1963 Mistral began a tradition of Maserati Grand Tourers and sports cars named after winds. It was famed Italian designer Giorgetto Giugiaro’s Maserati Ghibli that really put the Trident on the sports car map though, duelling it out with new Lamborghinis and Ferrari’s majestic Daytona. The Ghibli outsold both of them with production quadrupling over the initial plans for 100 examples, and many say to this day the Ghibli was the better, if less appreciated car. Orsi, however, couldn’t keep up and invited a new partner on board: Citroen. It wasn’t to be Maserati’s finest hour.

By the 1970s the company was totally different, incorporating Citroen’s hydraulics in its cars and churning out that ill-conceived, front-wheel drive, second-generation Quattroporte. All 13 of them. But Citroen was ambitious, greenlighting several new model lines such as the Merak and Bora, the latter becoming the first ever mass-produced mid-engined Maserati. The French intentions were good, but nobody could predict the 1973 oil crisis, nor that Citroën would go bankrupt the following year. The Italian government stepped in, and after a bit of a mess Maserati carried on in the hands of Argentinian former racing driver Alejandro De Tomaso.

Maserati’s third major era was upon it and the company was forced to completely abandon its storied Grand Tourers and mid-engined sports cars in favour of cheaper (and as it would turn out, infamously unreliable and badly built) front-engined saloons.

The lowest point came when the new managing director, De Tomaso, invited his friend Lee Iacocca, who headed Chrysler, to come and have a play. Chrysler ended up purchasing part of the company, which resulted in an embarrassing abomination of a car called the Chrysler TC.

Italy could stand it no more and, in 1993, Fiat came back into the Maserati story and fully acquired the company. As much as the Italian conglomerate mercilessly butchered Lancia (and continues to murder it slowly), Fiat actually ended up being the best thing that may have ever happened to Maserati.

Two decades into ownership and Maserati is still enjoying its fruitful renaissance with previously unimaginable sales figures, and Chrysler somehow ended up back in the fold since Fiat recently bought that company, too. No more Chrysler TCs, please, but we’ll take all the glorious Quattroportes, Gran Turismos and Ghiblis we can get. Rodolfo did good.

[ weekend@thenational.ae ]

Follow us @LifeNationalUAE

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.