Pity the Nation. That is the title of Robert Fisk's tome documenting the Lebanese civil war, which raged from 1975 to 1990, killing more than 120,000 people. Israel invaded and occupied parts of Lebanon for almost three years, sparking the massacre of Palestinians at Sabra and Shatila. An additional 76,000 Lebanese were displaced within the country, while an estimated one million fled abroad. Just as Beirut was partitioned by the notorious Green Line, so the fighting divided families, ruined communities and led to endless, bloody reprisals, the spectre of which still linger to this day.

So why is Vetements using it in its spring summer 2020 collection?

The fashion show – designed by Georgian designer Demna Gvasalia – took place inside a McDonald's in Paris, and was a role call of assorted references. Police riot gear turned up over delivery man outfits, and police badges hung around necks in pouches. Bose – the speaker company – was emblazoned across a T-shirt, while a Guantanamo Bay orange jumpsuit had a 'capitalism' name tag, but now crossed out. There were Planet Hollywood and Playstation logos, and even zombie make-up – all there in Gvasalia's typically experimental style, pushing boundaries and turning the norm on its head.

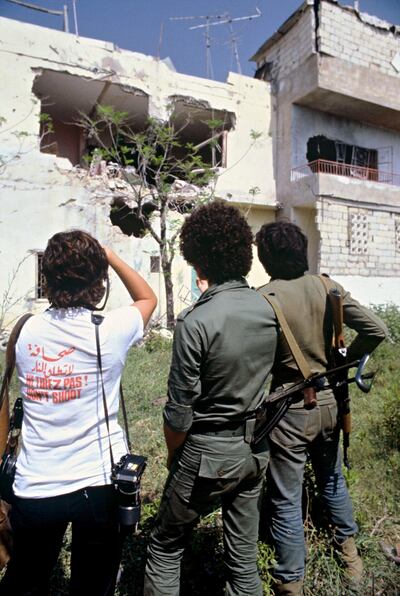

Then came a T-shirt, worn with blue track pants, printed in bold red the words “Don’t shoot” in Arabic, French and English. The brand name Vetements appeared underneath.

While Gvasalia has never had a problem taking social markers and recycling them into fashion, this exact T-shirt was first used in Lebanon in 1982, during the Israeli-Lebanese war, and worn by journalists. Handed out to those covering the fighting, it was hoped the words ‘Don’t Shoot’ in three languages would ensure the press were not shot at by any of the innumerable factions.

Not the first time the ‘Don’t Shoot’ T-shirt has been referenced

As a UAE national, menswear designer Khalid Qasimi is all too aware of the power and significance of this T-shirt, both in Lebanon and the wider region.

So much so, that for his autumn winter 2017 collection, he reworked the original 1982 design as a commentary on ongoing Middle Eastern tensions.

As he explained to the sneaker head website Highsnobiety, “This T-shirt was something very personal to me. It was a T-shirt reworked from the original Beirut 1982, during the war between Lebanon and Israel. It was a T-shirt that was given to the press. We’ve reworked it to highlight issues of the Middle East and what’s happening in the Middle East at the moment.”

On June 22, that same T-shirt appeared, almost verbatim on the runway at Vetements' show, folded into a collection laden with popular culture references. Designer Gvasalia hails from Georgia, which last time I checked isn't in the Middle East, nor is it in Lebanon. While Gvasalia enjoys a well deserved reputation as the enfant terrible of fashion, and industry disruptor, quite why he decided to reference a war is anyone's guess. Clearly this is a man who enjoys obscure references, and wink-if-you-get-it name checks, and while in Paris "Don't shoot' written in Arabic may be a sly subversion (especially against the back drop of recent terrorist attacks), in this part of the world it seems crass and exploitative.

That Gvasalia has ripped off a small designer is bad enough. That he is using a war to sell T-shirts is fairly cynical. Will it sell? Undoubtedly. Will it be used to highlight and honour in Paris the thousands of people who died in the war? Sadly, the answer will probably be no.