What started as a triumphant week for Abu Dhabi’s architectural scene was soon marred by some distressing but all too predictable news.

On Monday, the National Pavilion United Arab Emirates - la Biennale di Venezia announced an important first. The curator of next year’s UAE pavilion at the Venice Biennale will be Dr Khaled Alawadi, an assistant professor of sustainable urbanism at Abu Dhabi’s Masdar Institute.

Just as Sheikha Hoor Al Qassimi was the first Emirati to curate the UAE’s national pavilion for the Venice Biennale’s international art exhibition, Dr Alawadi will be the first UAE national to curate its architectural equivalent.

On the same day, the annual American Architecture Prize announced the list of its 2017 winners, which featured Abu Dhabi’s Wahat Al Karama, the Idris Khan-designed memorial, pavilion and landscape that sits opposite the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque.

Read more: Abu Dhabi's Wahat Al Karama wins 2017 American Architecture Prize

If the fortunes of the emirate’s architectural present and future look positive, Tuesday dawned with an anguished message about its past when a contact called to warn me about the imminent demolition of an overlooked but very special building, one more loss in a memory-obsessed city that struggles to keep hold of the fragments of its past.

At first sight, the only remarkable thing about the structure I’ll describe as the Rashid Bin Aweidah building is the contrast between it and the soaring towers that surround it on the south side of Hamdan Street, especially its neighbour, the Crowne Plaza Hotel.

But for those used to looking at old buildings in the capital, the fact that the building is only 3 storeys tall suggests that it might be of some age in UAE terms, something confirmed by the fact that its crumbling façade is resolutely flat, rather than jutting out at mezzanine level by 1.5 metres, a defining characteristic of almost all post-1970 buildings throughout the city.

The thing that really distinguishes the Rashed Bin Aweidah building, however, is the fact that not only is its history known, but that the man who oversaw its construction is still alive and living in Abu Dhabi and can remember the event with almost total recall.

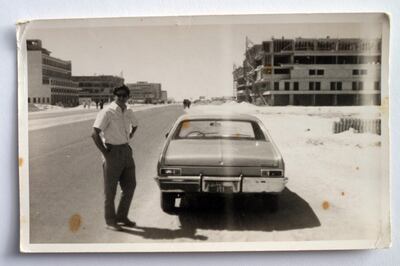

When David Spearing, now 81, arrived in Abu Dhabi as a young engineer in July 1968, not only was Abu Dhabi still a part of the Trucial States, but Hamdan Street was one of only two asphalted roads in city, the other being Airport Road.

The Abu Dhabi Municipality had only just marked out the limits of the plot that had been gifted to its new owner, Rashed Bin Aweidah, with a series of pegs driven into the sand and it was Spearing’s job to oversee the building’s construction.

Like all of the modern buildings that were being built in Abu Dhabi at the time, the Rashed Bin Aweidah building had been designed elsewhere, in this case in Pontefract, Yorkshire, in the drawing office of Spearing’s new employer, JGL Poulson Ltd.

In British architectural and political history, John Garlick Llewellyn Poulson’s name is now synonymous with one of the most devastating corruption scandals of the 1970s, but at the time of Spearing’s employment, the firm was the largest employer of architects in Europe.

Not only spearheading the Modernist transformation of Britain’s once industrial north, Poulson’s was also engaged in winning work worldwide, seeking employment in Nigeria, the Gambia and Libya and being awarded a £1.5 million contract in Malta, where it designed Gozo’s new Victoria Hospital.

__________________________

Read more:

[ Abu Dhabi's Wahat Al Karama wins 2017 American Architecture Prize ]

[ Masdar professor to curate the UAE National Pavilion at 2018 Venice architecture Biennale ]

[ History hides in a diamond that has long lost its sheen ]

__________________________

As David Spearing remembers, the modest building took less than a year to complete, using architectural drawings flown in from England – there was no way of producing or reproducing architectural plans in Abu Dhabi at the time – and the services of the Dubai Contracting Company.

As soon as the building was finished, it was populated by businesses overseen by Mr Bin Aweidah, such as Abu Dhabi’s Westinghouse Electric Corporation concession, which continued to occupy its ground floor until earlier this year, while its rooftop penthouse was let to the manager of the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands Research Station on Saadiyat Island, which at the time was accessible only by boat.

Now an Abu Dhabi institution, David Spearing went on to have a long and illustrious career throughout the UAE, working as the engineer on projects such as a new, Corniche-facing office building for Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, who was serving as the Ruler’s representative in the Eastern Region at the time, and only retiring at the turn of the millennium after he had worked as a consultant on the engineering of the Sheikh Zayed Cricket Stadium.

After 49 years, the building Spearing believes to be the oldest extant commercial property in Abu Dhabi looks set for oblivion, remembered only in the memories of its second oldest British expat. What more can be done to stop such a loss?