The recent pledge by the UK foreign minister, William Hague, to strengthen the role of human rights in British foreign policy and set up an independent advisory body to do just that has done little to lift the spirits of one group of people whose human rights have arguably been serially abused by successive British governments for more than 40 years.

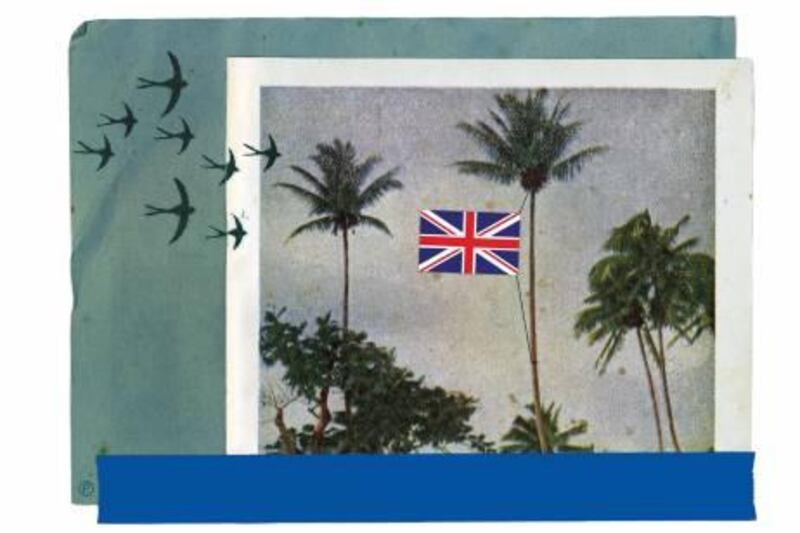

The Chagossians of Diego Garcia and the other islands of the Chagos Islands, better known as British Indian Ocean Territory, have spent most of those years attempting to get back to their homeland, from where they were so unceremoniously booted off by Harold Wilson's Labour government in 1968 to make way for a US airbase on Diego Garcia. The airbase is often referred to as the United States' "floating fortress" in the Indian Ocean, and remains as key for support operations in Afghanistan as it was for US operations in Iraq.

Last weekend, more than 100 Chagossians and international campaigners met in Mauritius, from which the islands were separated by Britain when that country gained independence in 1968.

A list of demands was endorsed, including chartering a ship, which could include Mauritian government and opposition leaders, to voyage to the Chagos Islands and plant the Mauritian flag.

This would almost inevitably guarantee an incident on the high seas, as all previous attempts by the Chagossians to make return visits without permission have been turned back by US warships. Campaigners also want to ensure that Mauritian sovereignty and "right to return" is firmly on the agenda of both the United Nations General Assembly next year and the International Court of Human Rights in The Hague. Mauritius continues to claim the islands as its own.

Washington and London are well aware that although the islanders are few in number - about 4,000, and mostly exiled in Mauritius and the UK - their case has attracted growing international attention as the facts have become known.

One would wish that the United States in particular is hoping for some settlement to one of the world's longest running disputes; after all, its lease to the airbase on Diego Garcia runs out in 2016. The United States has also plans to further expand the base.

As with the Greek myth of Tantalus - who, every time he tried to take fruit from a tree, the branches were raised out of reach - each time it looks as though the islanders may finally have won in the British courts, new obstacles are placed in their path.

After a decade of legal action and several notable victories in the courts, two years ago the Chagossians lost the ultimate battle when the House of Lords - now the British Supreme Court - ruled by three votes to two that their eviction had not been illegal.

In a new development, it was confirmed last weekend that the Chagossians will take their case to the European Court of Human Rights early in the new year in an attempt to overrule the British Privy Council.

Subsequent to the House of Lords ruling, David Miliband, the then foreign secretary, rubbed salt in the islanders' wounds by announcing that British Indian Ocean Territory was to become a "protected marine zone", not only taking away any fishing rights the islanders might one day enjoy - but giving more rights to molluscs than Chagossians.

The marine protection zone has just come into effect. In truth, Mr Miliband, along with all of his predecessors - bar the late foreign secretary Robin Cook, who did try to right this historic wrong - have grovelled before the US State Department, even as Diego Garcia was being used for extraordinary rendition and the holding of terrorist suspects without trial, actions that are illegal on British territory and that were repeatedly denied by UK government ministers.

This spring, William Hague, who was then the shadow foreign secretary, made this bold promise to the Chagossians: "I can assure you that if elected to serve as the next British government, we will work to ensure a fair settlement of this longstanding dispute," the islanders cheered to the rafters. Mr Hague has since expounded on his theme, saying: "In our first 100 days we have brought the energy of a new government to bear on the promotion of human rights."

In opposition, the Liberal Democrat leader, Nick Clegg, was even more outspoken in support of the human rights of the Chagossian islanders. His office went on record saying: "Nick and the Liberal Democrats believe the government has a moral responsibility to allow these people to at last return home."

The islanders' leader, Olivier Bancoult, wrote to the foreign office minister, Henry Bellingham, reminding him of his bosses' words and politely inquiring when exactly his people might be allowed to go back home.

Back came Mr Bellingham's reply in early autumn: "The UK government will continue to contest the case brought by the Chagos Islanders to the European Court of Human Rights. This is because we believe that the arguments against allowing resettlement on grounds of defence, security and feasibility are clear and compelling."

So what exactly are these champions of human rights, Messrs Clegg and Hague proposing to do now? Being charitable, it is just possible that the promises made by the parties when they were in opposition have not been transmitted to the foreign office.

But given the record of successive politicians of saying one thing in opposition and doing another in government, this seems unlikely.

Having said that, with just a little bit of imagination and goodwill, there may be a way ahead that could settle the concerns of all of the protagonists: hand the Chagos Islands back to Mauritius, but allow the western half of the island of Diego Garcia, which contains the massive US military base, to become a "British Sovereign Base Area", similar to the sovereign bases maintained by Britain on Cyprus. The area could then be re-leased to the United States.

This should not preclude any islanders from returning to Diego Garcia, or seeking work on the military base.

Many islanders are too young to remember their homeland, yet still the majority wish to go home. What possible security risk could emanate from these people, who are minded to restart their lives in islands away from the main airbase on Diego Garcia? And even if they did wish to return to Diego Garcia, not only is there plenty of room (half of the island is still pristine, forested and contains some of their old settlements), but they could make for a ready pool of labour on an airbase that is unlikely to be vacated for the foreseeable future.

* The National