Every month, Ifeyinwa Abel, the secretary of a church in Lagos, spends as much as a quarter of her salary sending money to pay for diabetes drugs to her mother 430 miles away in Abia Ohafia, a small agricultural village.

It isn’t easy. First Ms Abel, 35, has to go to a bank branch in Lagos, the country’s commercial hub, and transfer 6,000 Nigerian naira (Dh61) into the account of a friend in Ebem Ohafia, another town in Abia state. Then she’s got to pay 2,000 naira to 4,000 naira for her 65-year-old mother, Uche Arua, to get on the back of a motorcycle and ride eight miles from her village to Ebem Ohafia to pick up the money.

At least that’s what happens if this fragile arrangement doesn’t break down. Some months, Ms Abel cannot afford the motorcycle fare; other times, rains make the dirt road impassable. “Sometimes I am unable to send the money, and she stays without the drug, and I am pained,” Ms Abel says. “She must get the money and buy her drugs to survive.”

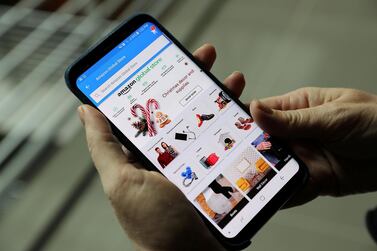

Ms Abel’s story would be unusual across much of the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa. In a region that accounts for half of the world’s 866 million mobile banking and payment accounts and two-thirds of all money transferred by phone, Nigeria is a laggard. There are an estimated 172 million mobile phones in the country, but it didn’t award a single mobile banking licence until July, when it gave one to South Africa’s MTN Group. Its foot-dragging — encouraged by the traditional banking sector, say industry analysts and telecommunications companies — is blamed for declining financial inclusion in this country of almost 209 million people.

Nigeria vies with South Africa as the continent’s largest economy and is its most populous, but it’s a “sleeping giant” in the world of FinTech, according to GSMA, a trade body that represents 750 mobile phone operators globally. Across sub-Saharan Africa, the adoption of mobile payments, which incur lower costs than traditional banking, has helped bring financial tools to the masses.

Financial inclusion in the region grew by more than 8 percentage points from 2014 to 2017, to an average of 43 per cent, according to World Bank data. In Nigeria the rate dropped almost 4 percentage points, to 39 per cent — far short of the Central Bank of Nigeria's target of 80 per cent by 2020.

Even with its new licence, MTN doesn’t look much like a bank: It cannot lend money or pay interest. In Kenya, by contrast, Safaricom acts much more like one. Part-owned by a unit of Vodafone, it launched its M-pesa app in Kenya in 2007. Today 22 million people, almost half of the population, use M-pesa as a mobile bank — buying groceries, borrowing money, transferring cash. “There’s no excuse for not sending money home because it’s now very easy,” says Kip Ngetichi, a 28-year-old waiter in Nairobi, who, with a few keystrokes, sends money twice a month to his mother 240 miles away in the western town of Kitale.

Telecoms companies and analysts say Nigeria is straggling behind its neighbours because its banks successfully campaigned to forestall the introduction of mobile payments. “The banks have been lobbying hard to protect their interests,” says Christophe Meunier, a senior partner at Delta Partners Group, an advisory firm for technology and media companies.

The new law, critics say, is hardly a cure-all; indeed, the way it’s structured will likely slow MTN and its rivals in line for licences — Bharti Airtel, Globacom, and 9Mobile — in their attempts to roll out services. Without the ability to lend or pay interest, mobile operators may struggle to encourage people to keep money in their accounts, says Usoro Usoro, the general manager of mobile financial services for MTN Nigeria. “Mobile money in its delivery is intrinsically a collaboration of multiple industries,” he says. “We haven’t received as much collaboration as required.”

As things stand, says Mr Meunier, “the way the legislation is written, even now, is very favourable to the banks.”

With 61.5 million subscribers and a network that spans all of Nigeria’s 774 local government jurisdictions, MTN can offer a larger consumer base than any of the nation’s banks. It plans to accredit 500,000 agents just to pay money out to recipients of mobile transfers if they want hard cash. Still, Mr Usoro says, adoption of the technology will be slower than it could have been if regulators had allowed MTN to provide a wider range of financial services, including savings accounts and loans. “For mobile money to make the impact that we’ve seen in other African countries, it needs to be utilised as far more than a simple money-transfer business,” he says.

For their part, Nigeria’s banks are adamant that they haven’t intentionally slowed the introduction of mobile money. They blame the country’s low literacy levels and poor financial infrastructure in rural areas. Nigeria’s literacy level is 51 per cent, compared with 79 per cent in Kenya, according to the World Bank.

“Financial presence as well as financial literacy is not adequate in rural and remote areas,” says Iphy Onibuje, head of digital banking at Lagos-based Fidelity Bank. Digital transfers only began to be piloted in 2012, she says. To win more business, she adds, the bank is willing to partner with mobile phone companies that have greater reach into rural areas.

As inadequate as the new legislation is from the standpoint of the mobile phone companies, their services are hugely in demand and are expected to take off fast as more licenses are granted. The country’s adult population of 111 million — which dwarfs the 64 million in Ethiopia, another major sub-Saharan country where mobile banking has made limited inroads — is a big draw for providers.

The presence of two large mobile phone companies that have track records and extensive operations in other countries — MTN and Bharti Airtel — will probably accelerate the take-up of services in Nigeria, Mr Meunier says. “MTN and Bharti Airtel will be pushing their platforms, and I think the other two will follow suit,” he says.

For Ms Abel, who also often sends home a little extra to pay people to help her mother with ploughing and weeding around her plot of land, that can’t come soon enough. “I have heard about mobile money,” she says. But for her, even now, the idea that you can move money through an app on your phone still seems a distant fantasy.