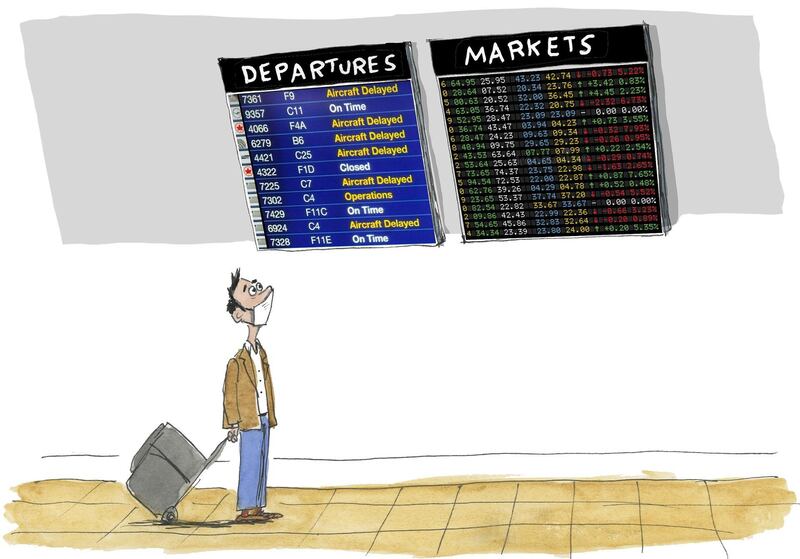

I bet you’ve considered staying in one place for the moment, turning down flights to conferences or meetings abroad and perhaps postponing that holiday you’ve been planning for a while.

News of the coronavirus is everywhere and it’s scary for your health – and your pocket.

There's certainly plenty to be scared about. The ability of a virus to halt travel and harm consumption are some of the ways an outbreak can have economic implications that spread far.

At the centre of this is our interconnectedness, especially when you consider our deeply integrated global supply chains, and social media’s role in spreading ‘news’ and information.

It makes markets more vulnerable and volatile, reacting to events as they unfold, wherever they may be.

At the time of writing this, shares in the sportswear company Under Armour – which has around 18 per cent of its production in China – had taken a double-digit dive, with the company issuing warnings that the full-year results could show further financial impact of the virus.

Meanwhile, Singapore’s tourism board is warning of a "significant hit" in terms of income due to the outbreak. And the US Federal Reserve’s semi-annual report, released at the end of last week, stated the coronavirus is a new risk to the global outlook.

Back in China, where it all started, the economy was already struggling. Last month, Chinese officials announced the country's gross domestic product grew 6.1 per cent – the lowest in three decades. Couple this with the fact that China’s economy makes up roughly 19 per cent of the world’s economy – versus 8.7 per cent during the Sars outbreak of 2002/03 – and you can see how disruption to China’s economy and factories can be significant, and far reaching.

At the World Economic Forum last month, an article entitled "A global economy without a cushion" by American economist Stephen Roach stated:

"With the benefit of full-year data, only now are we becoming aware of the danger the global economy narrowly avoided in 2019. According to the IMF’s latest estimates, global GDP grew by just 2.9 per cent last year — the weakest performance since the outright contraction in the depths of the global financial crisis in 2009 and far short of the 3.8 per cent pace of post-crisis recovery over the 2010-18 period."

In short, things are not looking good.

Many question if coronavirus is a black swan, with some pondering whether it will be the catalyst that will sink the markets. A black swan is a highly improbable event with three principal characteristics: it is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random, and more predictable, than it was.

To get some perspective, let’s take a look at how markets reacted and performed during, and post, previous viral outbreaks.

Historically, Wall Street’s reaction is short-lived. Here are a couple of examples.

Sars 2002/03: Dow Jones market data shows the S&P 500 gained 14.59 per cent, based on the end-of-month performance for the index in April of 2003. It posted a gain of 20.76 per cent for the same month a year on.

Avian flu 2006: It was up 11.66 per cent in the six months after reports of the virus first surfaced and up 18.36 per cent a year on.

The same has happened elsewhere. Charles Schwab data that tracks the MSCI All Countries World Index, shows the index gained an average 0.4 per cent in the month after an epidemic, 3.1 per cent six months after and 8.5 per cent 12 months later.

Each time there was an initial wobble, then gains.

So are the markets immune to viral outbreaks?

As you know, every investment comes with the caveat: past performance is not a guarantee for future results. However, during the writing of this article, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell stated that “the US economy is in a very good place, performing well”.

We've also seen US and European indices hit record highs again; Hong Kong clock its first gain in three sessions, and there’s been marginal recovery in Chinese stocks.

Basically, investor nerves are calming down and this latest epidemic is mirroring past trajectories with equities recovering three to four weeks after an outbreak.

Just because it appears history is repeating itself, it doesn’t mean it will stay this way. No one knows what this viral outbreak will ultimately mean to our interconnected world.

Just as you don’t want to travel to avoid potentially exposing yourself to the virus, keep your investments very still too.

Nima Abu Wardeh is a broadcast journalist, columnist, blogger and founder of S.H.E. Strategy. Share her journey on finding-nima.com