The Lebanese take holidays very seriously. In a country with 18 official religions, no one is overlooked. According to the central bank's website, there are 21 days off a year for various feasts and commemorations. There is one to mark the 2005 assassination of the former prime minister Rafiq Hariri,and another to commemorate Hizbollah's liberation of south Lebanon from Israeli occupation in 2000.

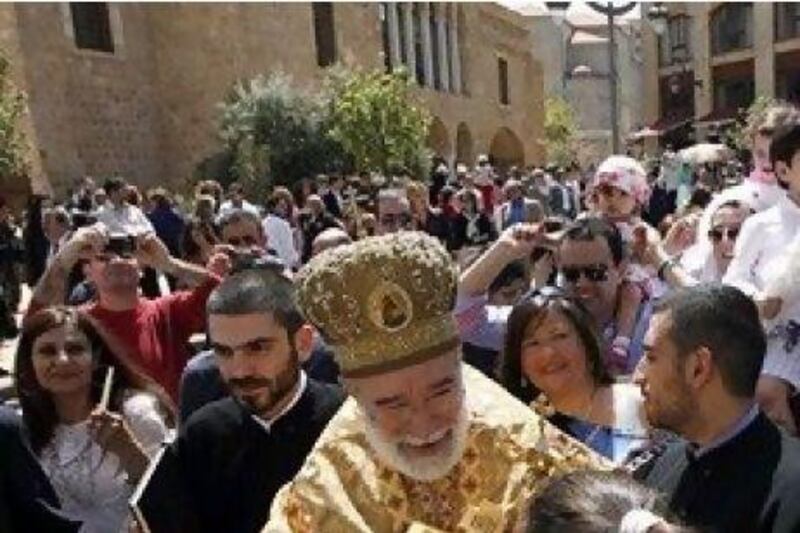

I mention this because it is the Easter season, one of the biggies. Between last Friday and next Monday, the country will have had six official days of holiday, to satisfy the demands of both the western and eastern churches.

The British can also be militant about days off. The Centre for Economics and Business Research is concerned. It has calculated that the United Kingdom, with its eight bank holidays, loses about £18 billion (Dh105.16bn) a year (the equivalent of 1.3 per cent growth) by people not going to work - and that's taking into consideration money generated on holidays by theme parks, zoos, restaurants, petrol stations and the like. Britons may work an average of 1,600 hours a year, but that's nothing compared with the South Koreans, who clock up an impressive 2,200 hours at the coal face.

Such weighty issues do not burden the Lebanese. Why should we worry about loss in productivity when the government clearly doesn't place much store in it in the first place?

Last week I banged on about our chronic and acute lack of electricity (in the World Economic Forum's [WEF's] Global Competitive Report for 2011-2012, Lebanon ranks 141 out of 142 in "quality of electricity supply"), but this has been a relatively easy obstacle to jury-rig, what with the advent of a grey market. Appalling internet penetration, on the other hand, is proving trickier to hide behind.

Now comes a report issued by the WEF that tells us that the competitiveness of the Lebanese economy is significantly impaired by weaknesses in the IT sector that deny it the "capacity to take full advantage of economic opportunities accruing from the deployment and use of technologies". Lebanon ranked 95th out of 142 countries and was 11th among the 15 Arab countries in network readiness.

Last October, we were assured that the days of having to wait for our favourite YouTube clips to buffer were over. The fibre-optic cables were in place; and the pricing issues had been resolved. The switch that could take us to online bliss could finally be flicked. And yes, for a tantalisingly brief period, things were much faster. They still are, but somehow we appear to have lost 50 per cent of the initial gain.

Now we are told by the telecommunications ministry that in the coming months there will be a tender for a new project to link residential buildings to something called an FTTx system, the last piece in the nation's fibre-optic backbone. But wait. Nicolas Sehnaoui, the telecoms minister, also admitted that it would take three years for Lebanon's internet speed to match that of "advanced countries".

But the Lebanese are nothing if not optimistic. After announcing plans to upgrade its broad fibre- optics network to a utopian 100 megabits per second, Solidere, the company tasked with rebuilding the Beirut Central District (BCD), has declared that it wants to create a technology park to make the BCD an IT hub for small and medium enterprises. Not to be outdone, a few days earlier, the telecoms ministry told us that it had offered a piece of property it owns in the glamorous suburb of Dikwaneh to the information ministry to establish what it called a "Media and Smart City". Both ideas are bonkers if Mr Sehnaoui's predictions are accurate.

Three years? In terms of today's technology, that's a millennium. If Google is already talking about internet in spectacles, my laptop will be in my brain before the Lebanese have high-speed internet.

Michael Karam is associate editor in chief of Executive, a regional business magazine based in Lebanon