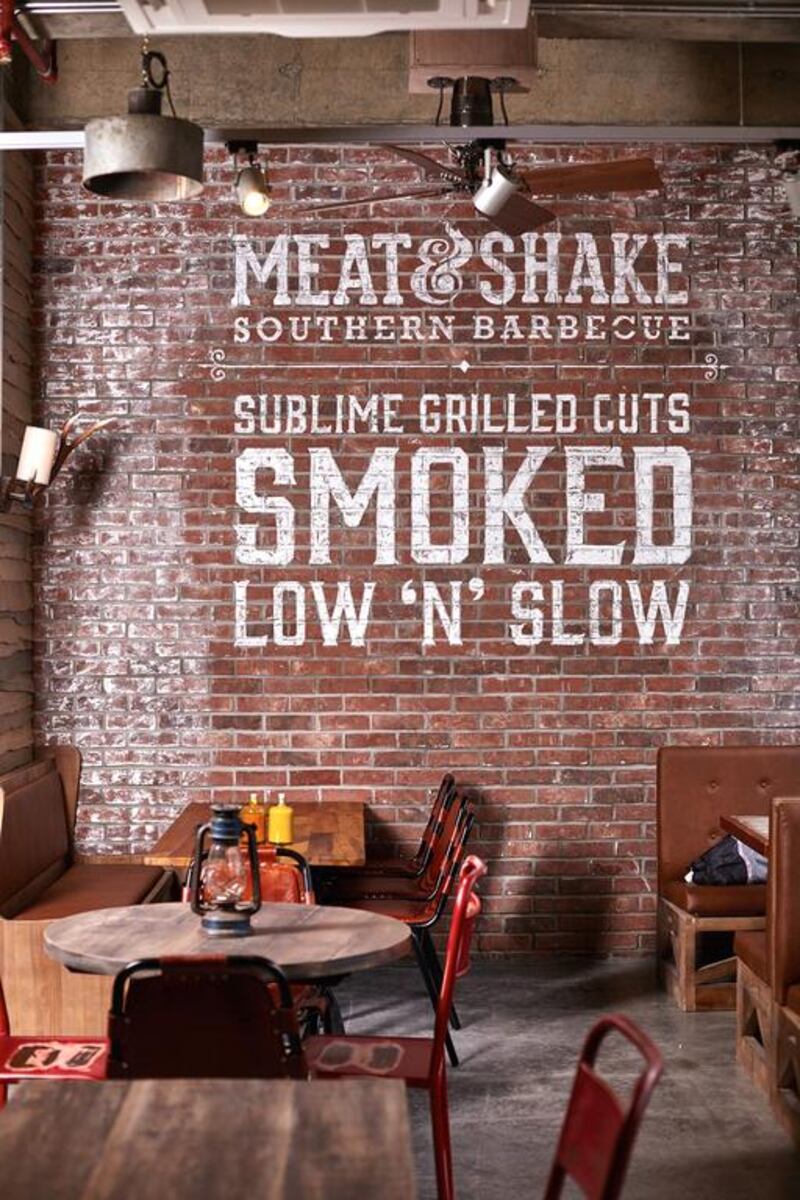

With Lafayette wings and spicy sausages among the starters, and burgers and steaks to follow, Meat and Shake restaurants offer classic smokehouse menus promising the flavours of the American south in suburban London.

But there is a striking difference that sets the growing chain apart in western catering.

All food and drink is served according to halal principles, so there is no wine list and the only beer on sale is non-alcoholic. And the “hot link” sausages are of beef and lamb, not pork.

It hardly seems surprising that the chain’s two founders, entrepreneurs of Pakistani origin, should now be seriously considering expansion into the UAE and other Muslim countries where such an approach would be entirely natural.

Yet there are already strong signs that Meat and Shake has also found a recipe for niche success in a British market dominated by restaurants with liquor licences. “We do have some walkouts from people who realise only after entering that we do not serve alcoholic drinks,” says Faraz Ahmad, who launched the business with a friend, Osman Ahmed, in 2010.

“A few react quite angrily, saying we have no right to operate the policy or that they won’t return because of it. There were even a tiny number of emails from people who somehow equated halal with terrorism.

“But we calculate the customer ratio at the restaurants at about 70 per cent non-Muslim so, for a lot of people, it is obviously not a problem. Families, in particular, seem quite comfortable knowing their enjoyment is not going to be spoiled by groups of loud, maybe drunken lads.”

The two men, who met as students working in the pizza franchises of Mr Ahmad’s father, considered allowing customers to bring their own wine or other drinks for consumption with their meals. This practice is adopted by many British restaurants without licences to sell alcohol.

But Sheikh Holdings, the UK, Muslim-owned family investment group that put up capital for Meat and Shake and has a 50 per cent stake in the chain, insisted there should be no deviation from the no-alcohol rule.

Mr Ahmad, 33, has never felt tempted to try alcohol. He believes Meat and Shake diners enjoy the range of soft drinks, milk shakes and mocktails on offer.

“We have no problem with people wanting a drink — I have plenty of friends who do and we just respect each other’s choices — but they can go to a pub before or after their meal,” says Mr Ahmad. “At one of our restaurants, a neighbouring wine bar even gives our customers a 50 per cent discount. “Commercially it is a major challenge for us because the mark-up on alcoholic drinks is so great and we miss out on that.”

Mr Ahmad and his partner, also 33, first entered business after leaving their respective universities determined to work only for themselves. They took British franchises from a United States mailbox provider, essentially offering businesses or individuals private postal addresses, and now run six “self-sufficient” central London outlets employing 25 people.

They branched out into catering in 2010, at the height of a boom for burger bars. At their first restaurant, in the south London district of Tooting, the response was so enthusiastic that people queued for up to four hours for tables.

It is still common for customers to wait 30 minutes or longer to be seated. This year, two more Meat and Shake restaurants opened, in Ealing, west London and in the town of Watford, 32km north-west of the capital, with an annual turnover now totalling £2.2 million (Dh12m). The mailbox service’s revenue is about two-thirds of that figure.

Mr Ahmad says they are now looking for potential Meat and Shake locations in central London and big provincial cities including Birmingham, Manchester and Leicester, with 2017 earmarked for possible expansion into the Arabian Gulf, perhaps starting with Abu Dhabi or Dubai. “It is a logical extension of our activity but, as Londoners, we really wanted to conquer the UK first.”

They pride themselves on ploughing most of the income they generate back into the business to facilitate growth.

People often assume Mr Ahmad and his partner must now be living luxurious lifestyles. “They think we must be rolling in it but I draw a salary of just £25,000 a year and I do not even own my own home,” he says. “If we were in this purely for money, we would have packed it in a long time ago. It is much more about building something, being someone and feeling proud.”

Mr Ahmad’s family came from Faisalbad, Punjab’s largest city after Lahore and settled in the United Kingdom in the 1960s. His father and grandfather suffered some prejudice after settling in Britain but have grown to love the country.

“I was practically the only Asian kid in my school growing up in Essex [north-east of London],” Mr Ahmad says. “There was a bit of racism. I think they thought I was some poor village boy from a family of asylum seekers, whereas my family have always been involved in business. I was quite an easy-going lad and learnt not to take it personally.”

Mr Ahmad believes an overwhelming majority of Muslims living in and around the UK capital feel as he does, proud to be Londoners and pleased to be British. “The reason I personally love this country is because of its great diversity and the fact everyone is free to practise their own religion,” he says. “The world would be a boring place if we all followed the same faith.

“The media doesn’t help community relations by concentrating on negative front-page news but I also think many Muslims could do more to integrate. When they do not integrate, and you get feelings of exclusion, that is when some people get drawn to extremism.”

Mr Ahmad now fully intends to build on his own wholehearted integration – his wife, Marie, 30, is a Czech-born fitness instructor from a Catholic background – as he develops the business further in Britain before turning an ambitious eye towards the Middle East.

business@thenational.ae