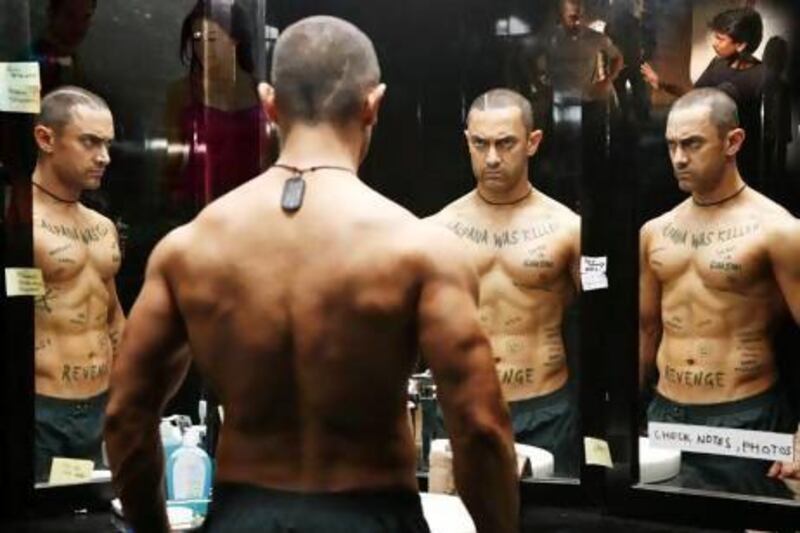

Ghajini, a 2008 Bollywood thriller inspired by Christopher Nolan's Memento, broke a record when it became the first movie to earn more than 1 billion rupees (Dh68 million) at the Indian box office.

Last year, nine Bollywood movies entered the illustrious 100 crore (1bn rupee) club, as Indian cinema reached new heights.

India's film industry, which is a century old this year, is experiencing strong growth. "In 2012 the India film industry had a brilliant year, mainly because the creative content was a hit with the Indian audiences," says Smita Jha, the leader of entertainment and media practice at PricewaterhouseCoopers in India.

India's film sector, which was worth 112.4bn rupees last year, is expected to grow to a value of 193.3bn by 2017, according to figures from KPMG. The typical ticket in India costs 160 rupees at a multiplex and 60 rupees at a single-screen cinema.

"Revenues are coming in from different sources," says Ms Jha. "Money is coming in from overseas, from television, digital rights, mobile."

The growth of multiplex cinemas versus single-screen venues and a booming satellite television industry, combined with the fact that it is cheaper and quicker to distribute digital films compared with 35mm film, are all factors that have contributed to higher revenues, she said.

Yet it was only in 2001 that the Indian government recognised film as an official industry. Before that, banks were not allowed to lend money to finance films. This led to much speculation that Bollywood productions were being funded by the criminal underworld and being used to launder money.

"Until that time, [filmmakers] were struggling to finance the industry," says Ms Jha. "The money had to be raised from all the other private sources and that was the challenge."

Even after it was recognised by the government, it still took time for Bollywood to become the more professional and corporatised affair that it is today.

"To get a loan from a bank, as in any other business, you need to show a project plan, how much you're going to earn from the project, and how you're going to repay the finance," says Ms Jha. "It wasn't just important to get the industry status - it was important to get the professionalism. The way films were being produced in India, it was pretty much an individual family affair - there was no structure.

"Corporates started entering into the business and now it's much easier for the film industry to secure financing and loans from the bank. The only challenge … is that our banks and financial institutions still don't lend 100 per cent of the project value - only 20 to 30 per cent."

As Indian cinema grows in popularity, actors are demanding more money. Salman Khan, one of Bollywood's highest-paid actors, received 600m rupees for his role in the blockbuster Ek Tha Tiger last year. The movie grossed more than 2bn rupees.

"While the cost structure varies based on the budget and star cast, artist fees continue to form a major component of a film's budget for most large productions," according to a recent report by Ficci and KPMG.

Most Indian films are produced in languages other than Hindi on a shoestring budget by smaller producers or family-run businesses. With the rise of multiplex cinemas, these films are now reaching a bigger audience.

Bollywood is also reaching a more global audience.

"It's not just Indians and south Asians who are watching our films," says Neeraj Roy, managing director of Hungama Digital Media Entertainment, a distributor of Bollywood content. "Bollywood in my mind is the new spice in international entertainment. It's got a certain kind of coolness about it in the way it's happening."