The most ambitious project unveiled by Google this year is not a smartphone, website or autonomous suborbital balloon from the Google X lab. You cannot hold it or download it, or share it instantly with friends. In fact, the first part of it probably will not exist for at least three years. But you can read all about it in hundreds of pages of soaring descriptions and conceptual drawings, which the company submitted in February to the local planning office of Mountain View, California.

The vision outlined in these documents, an application for a major expansion of the Googleplex, its campus, is mind-boggling. The proposed design, developed by the European architectural firms of Bjarke Ingels Group and Heatherwick Studio, does away with doors. It abandons thousands of years of conventional thinking about walls. And stairs. And roofs. Google and its imaginative co-founder and chief executive, Larry Page, essentially want to take 60 acres of land adjacent to the headquarters near the San Francisco Bay and turn it into a titanic human terrarium.

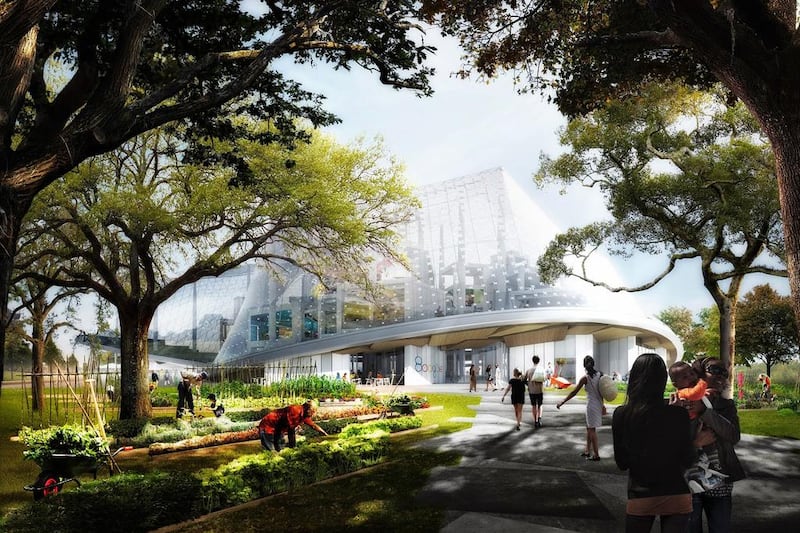

The proposal's most distinctive feature is an artificial sky – four enormous glass canopies, each stretched over a series of steel pillars of different heights. The glass skin is uneven, angling up and down like a jagged, see-through mountain. The canopies will allow the company to regulate its air and climate. Underneath, giant floor plates slope gently upwards, providing generous space for open-air offices and doubling as ramps so the 10,000 employees who will work there can get from one floor to the next without the use of stairs. For additional office and meeting space, modular rooms can be added, stacked, and removed as needed. To accomplish this, Google says it will invent a kind of portable crane-robot, which it calls crabots, that will reconfigure these boxes and roam the premises like the droids in Star Wars.

The plan is just as impressive from the outside. The canopies hug the ground like a biosphere on the surface of Mars, except in a few places where they dramatically curve upwards. Google is not planning to seal off its new campus but will keep it open to acres of manicured parks and restored coastal wetlands, with bike and hiking paths winding throughout. The company is pitching the project as a gift to the city where it has resided for the past 15 years – the parks and ground-floor retail plazas are meant to be accessible to residents, who can traverse nearby Highway 101 through two pedestrian overpasses Google also promises to build.

The proposed designs are full of ideas about the future of work. There are collaborative spaces and private perches, where employees can pop open a laptop away from distractions or the glare of the sun. Googlers will also be able to ride their bikes right to their desks. Parking lots are underground and hidden from view. Employees will have access to exercise equipment and yoga studios on majestic balconies overlooking central courtyards, although the renderings curiously omit railings and other safety barriers. Perhaps gravity will be different under the glass as well? With cafes and stores on the ground floor, and 5,000 units of proposed housing within an easy recumbent bicycle ride, there may be no reason for workers to ever leave.

Google’s search

To design its future home, Google has enlisted two young guns: 40-year-old Bjarke Ingels of Denmark and 45-year-old Thomas Heatherwick of England.

Mr Ingels’ firm, known as BIG, usually deals in massive projects with some demonstrable local-community benefit, while keeping a sense of humour. Recent efforts include a waste-to-energy plant in Copenhagen that has a ski slope on its roof and, in a clever aside, generates rings of steam through its smokestack rather than regular plumes. The idea behind the ring is to illustrate what one tonne of carbon dioxide, the greenhouse gas, looks like. BIG is also the lead firm on New York’s proposed Dryline, 16 kilometres of flood defence on the southern edge of Manhattan that will serve as home to a series of parks, playing fields and museums.

Heatherwick Studio operates on a slightly smaller scale. Trained as a furniture designer, not an architect, Mr Heatherwick started by rethinking benches, chairs and other conventional forms. His scope gradually expanded. In London, he redesigned the double-decker bus to make it more environment-friendly and accessible to the disabled.

Mr Page had talked to his real estate team about the old Building 20 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a 1940s wood-frame construction. It was ghastly to look at. But the “plywood palace”, as it was sometimes called, was beloved as an unruly nexus of interdisciplinary discovery. Wallboards and floors could be popped out and changed around, letting occupants – physicists, electronics researchers, linguists – mould their space however they wanted. Building 20 was a proto-incubator that begat a range of advances, from single-antenna radar to loudspeakers (Bose has roots there) to strobe photography, and was home to nine Nobel Prize winners. It was torn down in 1998 to make way for the larger, postmodernist Stata Center, designed by Frank Gehry. Mr Page “challenged us to look beyond whether we liked building A or building B and to consider what is happening inside the building and why”, says David Radcliffe, Google’s vice president for real estate.

By the spring of last year, Google had narrowed the candidates for its Googleplex expansion down to Mr Ingels and Mr Heatherwick. The real estate group spent a month internally debating the merits of each and flew them separately to Mountain View. The two lunched privately with Mr Page, who talked about why nature is so removed from the daily experience of Silicon Valley and his obsession with improving air quality, particularly because Google’s offices are so close to a major motorway. At the end of the deliberations, the Google executives decided not to choose one or the other. “The simple version is, Larry just liked both of us and said, ‘Why don’t we work together?’ ” Mr Ingels says.

Now, all Google has to do is convince its hometown that its intentions are not evil.

Reality check

In its development proposal, Google has asked Mountain View for permits to build 2.5 million square feet of offices. In a five-hour meeting on May 5, the city council, concerned about economic diversity and traffic congestion, allotted most of that space to LinkedIn, which had a competing proposal. Council members say there is some resistance to giving Google everything it wants, particularly extra housing, which could permanently tilt the city’s voting rolls in Google’s favour. “They are not the only company in town, and there is a significant amount of public pressure not to be a one-corporation town,” says Ken Rosenberg, a councilman.

Still, it is unlikely the council will entirely block Mr Heatherwick and Mr Ingels’ plans. Google received one parcel for its expansion and must now persuade the city to allow it to develop on another three.

Google did its best to conceal its disappointment with the decision. “We’re pleased that the council has decided to advance our Landings site,” Mr Radcliffe says. “Given the connected nature of our campus design, we will continue to work with the city to identify a process to move forward with this project.”

As Mr Radcliffe notes, no other company comes close to offering the same loaded package of community perks and environmental benefits.

Shareholders are unlikely to stand in Google's way. Investors have been tolerant of, and sometimes even jazzed about, the company's expensive "moon shots" such as self- driving cars, internet-connected glasses and broadband-broadcasting blimps. And Google does, after all, need the extra space for a head count that is climbing above and beyond 55,000. "This is a company with almost US$75 billion in cash on its balance sheet," says Ashim Mehra, a vice president at Baron Fund, which holds Google shares. "If it wants to use some of it to build an office that facilitates a better work environment and better collaboration, I think investors are generally supportive."

The true sceptics, really, are other designers, and they are not hard to find. Why, for example, do you need giant glass enclosures in a place where the weather is always perfect? “This is why hiring architects from northern Europe maybe was not the smartest thing,” says Louise Mozingo, a professor of environmental planning and urban design at the University of California at Berkeley. She also wonders how Google plans to clean the glass canopies when it does not rain for long stretches. “There is something about this whole microclimate that they are not quite getting,” she says.

Others doubt the practicality of the supposedly flexible design. How, they want to know, do you configure a stable electrical system in a set of modular office units that will be hoisted and moved around by crabots? “Flexibility can become really expensive,” says David Meckel, the director for research and planning at the California College of the Arts. Mr Radcliffe says the company has not worked out every problem just yet. “There may be a few things we need to scratch our heads on and figure out over time,” he says. He agrees the project should probably be considered another Google moon shot – a hugely ambitious idea that does not yet have a lot of supporting details nailed down. “It redefines the way we think about the relationship between the built environment and the work that happens there, and the community and ecology it sits in,” he says.

He adds that others probably should not try to copy the grand design. “This is absolutely the right thing to do for Google. I’m not sure it’s the right thing for anybody else.”

business@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter