The world gas industry has a problem: it is too good at producing and not good enough at marketing. Prices have collapsed, to the point that some exports are halting for a lack of willing buyers. Gas companies must get the pricing and sustainability of their product right, if their massive investments are to pay off.

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) has expanded enormously recently: demand grew 12 per cent last year, met by new plants in the US, Australia and Russia.

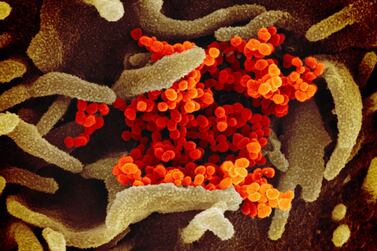

Most of the extra volumes went to China and Europe. China was switching coal-fired heating and industry to gas, a programme that has now slowed down, even before the coronavirus badly hit imports this year. Gas has helped push out coal in Europe, but much of the imports have gone into storage, which after a mild winter remains unseasonably almost full.

Now buyers have begun rejecting cargoes they cannot resell. Customers of Spain’s Naturgy chose to pay a fixed fee rather than take delivery of two LNG cargoes from Cheniere’s Texan facility. PetroChina has sought to invoke force majeure to avoid contractual penalties for not taking delivery. Still it’s debatable whether this is because of a shortage of workers to unload cargo as a result of the virus’s disruption of the logistics industry or simply because Chinese demand has collapsed.

US Henry Hub prices have slumped below $2 (Dh7.34) per million British thermal units (MMBtu), remarkably low for the usually high-demand winter period. Prices in Texas have gone negative – producers having to pay others to take their unwanted gas – leading to a surge in wasteful and environmentally destructive flaring. The usually pricey JKM market, for spot LNG delivered to East Asia, has dropped below $3 per MMBtu – the energy equivalent of oil selling for $18 per barrel.

The result is that, instead of capitalising on more expensive gas in the rest of the world, US producers have exported their low prices. Companies such as Centrica in the UK, and Chevron, Shell and America’s largest gas producer, EQT, have massively written-down the value of their gas assets. Chesapeake, one of the shale revolution’s standard bearers, has warned it may go bankrupt.

Yet gas companies remain very bullish on the longer-term. Shell’s annual LNG outlook, released on Thursday, shows a doubling of world demand by 2040, particularly in Asia. In 2018, the company committed to build the $40 billion LNG Canada plant. Total, BP and Middle Eastern national firms are turning to the fuel, cleaner and with apparently more assured long-term growth than oil.

Apart from a long line of new export projects from the US ranging from firm to speculative, other massive plans include Woodside’s $21bn for Browse LNG and $11bn for other expansions in Australia. Projects in Mozambique are advancing, and Mauritania and Senegal are new entrants to the race with a large joint gas-field operated by BP. Qatar recently delayed its search for international partners because of the price collapse, but still plans a huge expansion by 2024. Novatek’s $21bn Arctic-2 LNG facility in Russia was approved in September.

This huge wave of investment is in the teeth of a gale of oversupply. The companies hope that it will reach a safe haven of stronger demand in the middle of this decade. This faces three big problems.

First is the competition. The cost of solar and wind power in good locations, such as north-western Europe, the US Midwest and southwest, the Middle East and India, has fallen dramatically. At first, this will favour gas, as a flexible balancing fuel for variable renewable energy. But as coal power disappears entirely from markets such as the UK, and batteries improve, renewables will begin eating into the share of gas too.

Contrastingly, in countries such as China, India, Indonesia and Australia, coal is dirty and inflexible, but is strongly backed by influential incumbents, mining communities, and dependent businesses such as railways.

Second is the price. Most LNG is still sold on formulae linked to oil. This leads to a wide divergence of long-term LNG at $6 per MMBtu from spot LNG at $3 per MMBtu. Buyers cannot fully capitalise on low prices, and therefore cannot create demand by pushing out coal.

Third is the environment. Before it has had a chance to replace coal, gas is already under attack from environmentalists who decry its climate-warming methane leaks and deny that it can be a bridge to a sustainable energy system.

To meet these challenges, gas exporters need a combination of flexible pricing, demand creation and a cleaner vision. Gas will have to be sold on its merits, rather than linked to oil. That means making JKM and other LNG price markers more liquid and flexible, with tradable relations to continental benchmarks such as Henry Hub.

LNG will have to be cheap. That means new technologies and better project management to bring down the cost of the massive facilities that cool gas to a liquid so it can be shipped worldwide.

Gas companies need joint ventures for industries and power plants to buy their gas, in the emerging Asian giants as well as in new markets such as Africa. They have to build or commission pipelines to reach inland markets, and lobby for supportive regulation, including carbon prices and air pollution caps.

Finally, gas will have to be sustainable. Beyond just cutting methane leaks and flaring, companies need to embrace large-scale carbon capture and storage, as Adnoc is moving towards, and pioneer hydrogen or other decarbonised fuels. Reaching the promised bright future for gas is not about surfing a wave of demand but navigating through a narrow and perilous strait.

Robin M. Mills is CEO of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis