Live updates: Follow the latest news on Israel-Gaza

Cui bono? Who benefits from the current threat to shipping in the southern Red Sea and Gulf of Aden?

The Houthi forces claim to be defenders of the Palestinian cause. Iran needs to show it is doing something to stand up to Israel and demonstrate some retaliatory power after the assassinations of its operatives. But some less obvious players gain too.

The missiles, drones and small boat attacks have deterred the majority of container traffic. Now bulk carriers, and tankers of oil and liquefied natural gas, are increasingly steering clear of the area, with overall traffic down more than 40 per cent. Consumers suffer from delays and higher costs as insurance bills go up and ships are rerouted around Africa.

The strikes pose serious problems for littoral states. Saudi Arabia has kept its own tanker fleet moving, apparently feeling the risks for now are manageable, but some third-party shippers it uses have pulled out. Its crucial Red Sea ports face significant risks if they want to receive cargo from the south or send it to Asia.

This is troublesome for Yanbu and Rabigh, whose petrochemical industries are mostly focused on exporting to Asia, and for Jizan, whose major new refinery needs to receive crude feedstock from Saudi Arabia’s Gulf ports. Power and desalination plants along the coast need to get fuel, although they could pick up foreign fuel oil cargoes, for instance from Russia.

How could Houthi attacks in the Red Sea affect global trade?

The East-West pipeline, with its terminus at Yanbu, is mostly used to send cargo to Europe. It does provide Saudi Arabia with a crucial alternative outlet for crude if exports through the Gulf are impeded. But in that case, shipments would either have to head north or through the Bab Al Mandeb.

Egypt was already suffering an economic crisis. Container traffic through the Red Sea has almost ceased, and a drying up of oil and LNG tanker movements would further hit earnings from the Suez Canal. In its last financial year, Cairo earned $9.45 billion from the canal, almost a seventh of government revenue.

Since 2022, Europe has largely managed to replace Russian gas with imports of LNG, mainly from the US and Qatar. QatarEnergy has begun diverting its LNG vessels around Africa.

Fortunately for Europe, the current cold snap has been just a blip in an overall warm winter with ample gas storage and moderate prices. European gas prices have hardly responded to the trouble. But the continent should learn from 2022’s agonising crisis – its safety margin is increasingly thin. A big LNG surplus is on the way from 2026 and 2027 onwards, but only if there are no problems with Doha’s exports and its major LNG expansion projects.

The current Israeli government benefits from a sense of threat and chaos, inclining the US and Europe to keep backing it unquestioningly. Most of Israel’s modest oil needs come from its own output or suppliers to the Mediterranean such as Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan.

Further investment in its own offshore gas industry is hampered by a sense of insecurity and risk, and from unwillingness to depend much more on Egypt, which effectively re-exports some Israeli gas via underutilised liquefaction plants. But, if the disruption persists, Cairo and Brussels may see the value in more adjacent gas output.

From Tehran’s point of view, the current situation is ideal. Although it backs the Houthis, they also make their own decisions, so attacks launched from Yemen are at least one step removed. Iran gives a show of defiance, causes trouble for the US and distracts its regional adversaries, without being so provocative as to attract a direct assault on itself.

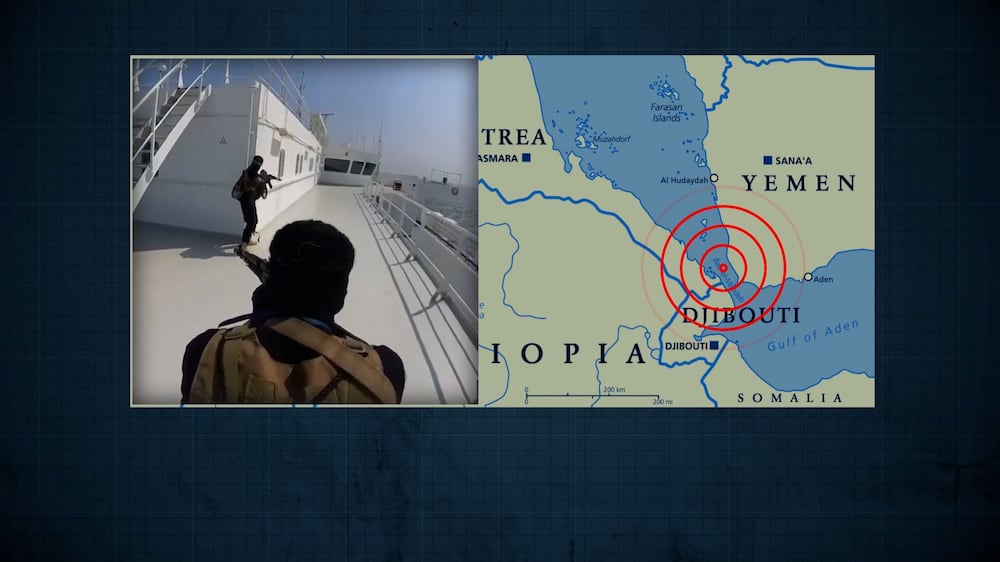

Except in extremis, Iran does not want to close the Strait of Hormuz or the Gulf, since virtually all its rebounding oil exports go to China. Stirring up trouble in the Red Sea is much more palatable. The boarding of a tanker in the Gulf of Oman on January 11 by the Iranian navy was probably a one-off since the same vessel had been seized by the US last year over allegations of transporting Iranian oil.

Meanwhile, Russia's tankers have also mostly continued sailing south through the Red Sea to their vital markets of India and China. Though two Russian-linked ships were attacked in December and on January 12, they were not damaged and these were probably mistakes or misidentifications. Constraining Europe’s gas supplies has not brought Moscow strategic gains yet, but might eventually.

The most interesting case, though, is China.

Other than from Russia’s western ports, its oil imports do not depend on the Bab Al Mandeb. Neither do its LNG purchases. It does not want any interruption to traffic through the Gulf, and this was a crucial part of the Iran-Saudi Arabia normalisation it brokered in March.

Its vital container traffic to Europe, carrying its vast manufacturing exports, is impeded, though, suffering the longer, costlier route around the Cape of Good Hope. That lends weight to European and American aims of limiting dependence on China’s goods. Chinese vessels braving the waterway have signalled their nationality, in the hope of deterring Houthi attacks.

Beijing has been very quiet on the Red Sea crisis, perhaps obeying Napoleon’s dictum, with regards to the US, of “Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake”. Although it has a military base in Djibouti, it has not taken part in operations to protect shipping.

Washington might think China is free-riding on the US. But it wants even less that Beijing would play an active role. The US fleets are in the Middle East less to protect its own interests than to avoid a vacuum that a rival might fill.

For now, China is willing to let the US bear the cost and shame of its aimless regional approach, where occasional missiles substitute for a serious diplomatic strategy. Yet again, a Middle East irritant distracts the US from much weightier long-term trouble, over Ukraine and Taiwan.

Beijing does not have the ability, inclination or need to play an active role in this region’s security – yet.

Robin M Mills is chief executive of Qamar Energy, and author of The Myth of the Oil Crisis